“I want to know what faith you have in the miracle at Guildford … All London is upon this occasion … divided into factions about it.”Letter from Alexander Pope to John Caryll, Dec 5 1726.

This affair has “… almost alarmed England, and in a manner persuaded several people of sound judgment that it was true.”Lord Onslow, note to Sir Hans Sloane.

Everyone was talking about it. News of it spread

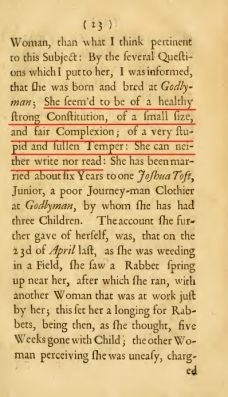

like wildfire. Mary Toft was a sensation. On Sunday November 20th

1726, Mr Cyriacus Ahlers, physician to the German household of King George I,

went to Guilford to meet her. On arrival, Mr Howard’s nurse brought news that

Mrs Toft was once again in labour.

|

| Rabbits, rabbits, rabbits |

Ahlers, assisted by Howard, presided over

the delivery of the loins and lower limbs of a young rabbit and was convinced

that this could not have been introduced into her uterus earlier. He gave Toft

a guinea and promised her a pension from the King then, claiming a headache and

a sore throat, at 5 pm he departed back for London. Doctors, surgeons and

obstetricians shuttled between London and Guilford and, inevitably, their

opinions differed. Sir Richard Manningham was convinced it was all an elaborate

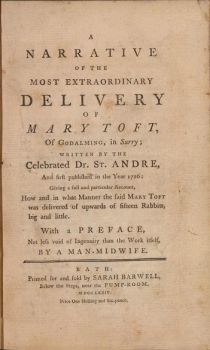

fraud; Dr St André was convinced it was a miracle.

|

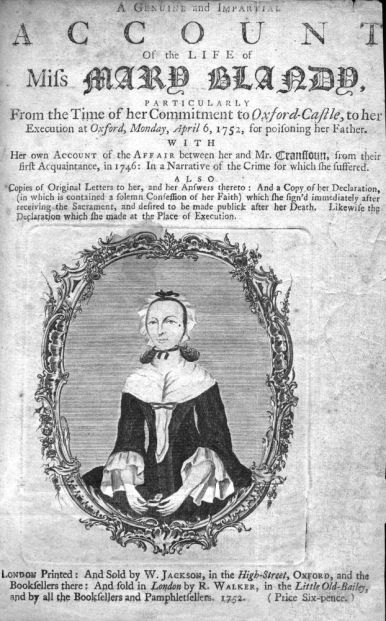

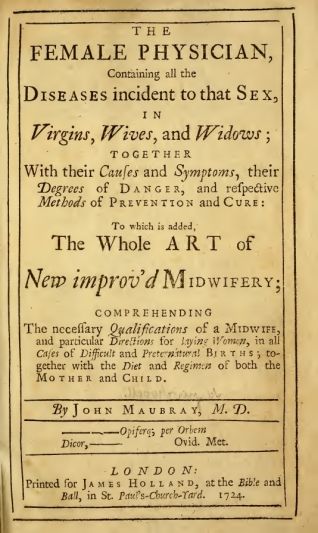

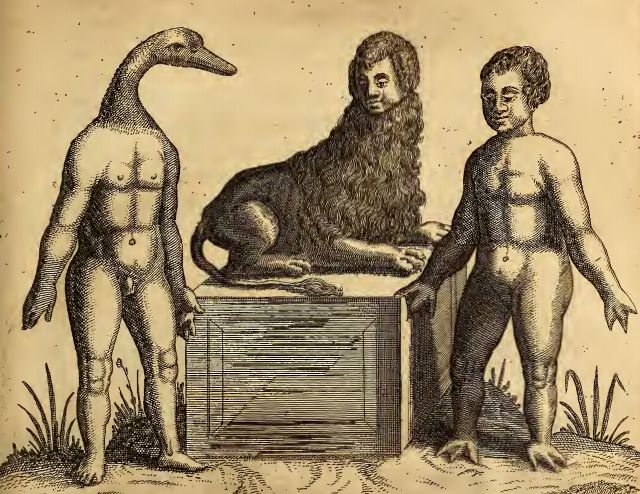

| John Maubray - The Female Physician - 1724 |

On November 29th,

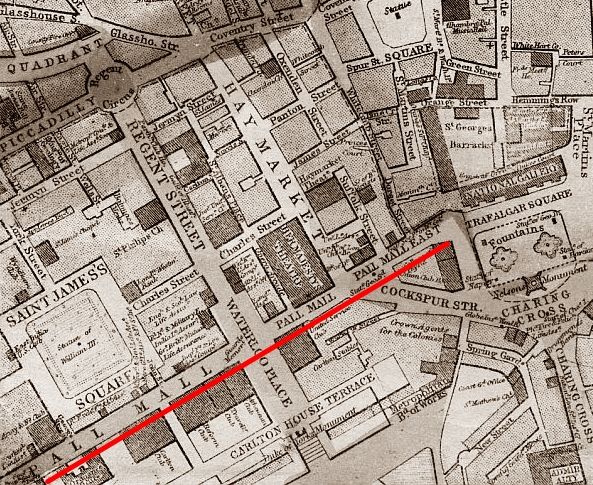

Mary Toft was brought to London and was lodged at Lacey’s bagnio (bath

house) in Leicester Fields, to where even more doctors flocked to see her.

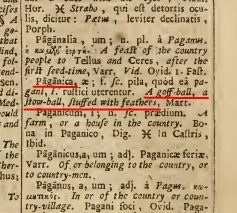

Amongst them was John Maubray, author of The Female Physician, a work in

which he describes the phenomena of ‘maternal impression’, a belief that women,

particularly pregnant women, could be influenced by exterior experiences that

were reflected on the bodies of their offspring.

|

| An Elephant Man |

John Merrick, the famous

‘Elephant Man’, was convinced that his own condition was the result of his

mother being frightened by a circus elephant when she was carrying him. Medical

literature of the day contains many examples of monstrous births that were

brought about by the encounters of mothers-to-be with various creatures, or

even, in some cases, by dreaming about animals.

|

| God only knows ... |

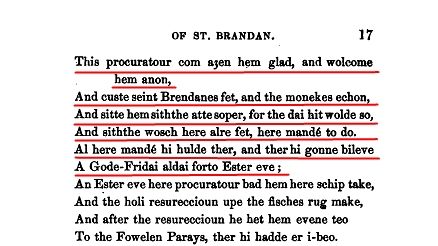

Maubray wrote about something

called a suyger, a word he translates as sooterkin, and describes

how, on a voyage to Holland, he witnessed the birth of just such a monster,

“Upon which occafion, in fhort I immediately lent her a helping Hand and upon the membranes giving way, this forementioned Animal made its wonderful Egrefs filling my Ears with difmal Shrieks, and my Mind with greater CONSTERNATION.”

|

| Maubray -The Female Physician - 1724 |

More disconcertingly, Maubray also describes how the wives of the sea-faring

Dutch expected at least one in three births to result in the production of a

suyger, and how the women prepared for these births

“…to receive it warmly, And throw it into the Fire; holding Sheets before the Chimney that it may not get off as it always endeavours to fave itfelf by getting into fome dark Hole or Corner. They properly call it de Suyger which is (in our Language) the Sucker, becaufe, like a Leech it sucks up the Infant's Blood and Aliment.”

|

| Your guess is as good as mine ... |

At Lacey’s, Manningham sat by Toft’s bedside as she went in labour yet again;

he examined her externally and internally, and although she exhibited labour

pains, there was nothing to indicate that she was about to give birth. These

pains continued for several days, with the sceptical Manningham in close

attention; he noted how she moved in and out of the pains, how she slept

fitfully, and how she ate beef, rabbit and (ironically) red herrings.

|

| Mary Toft |

Then, on

December 4th, Mr Thomas Howard, a porter at Lacey’s bagnio,

gave a sworn statement to Sir Thomas Clarges, Justice of the Peace, that Toft’s

sister-in-law, Margaret, had clandestinely approached him with a request to

procure a rabbit. Clarges immediately placed Toft under arrest and she was

closely questioned, but swore that the rabbit had been asked for as food. Her

sister-in-law, who was there to assist with the birth, also swore under oath

that the rabbit had solely been intended for eating.

|

| The Surrey Rabbit Breeder |

Unimpressed, Clarges

intended to imprison Toft until Manningham intervened, urging caution on the

off chance that Toft was still about to deliver more animal parts, regardless

of their origins, and with great difficulty he managed to persuade Clarges to

allow her to remain under the custody of the High Constable of Westminster at

Lacey’s. Two days later, Clarges threatened Toft with much more severe

treatment, which seems to have worked as, in the presence of Manningham, Dr

Duncan, Lord Baltimore and the Duke of Montague, Mary Toft began her

confession.

|

| Much Ado About Nothing - 1727 |

She had, she said, miscarried her natural child and it was then,

when her cervix was dilated, that an unnamed accomplice had introduced the

monster (as she termed it) into her uterus. This was the body of a cat and the

head of a rabbit, and the accomplice had assured Mary that she would never need

work again if she continued with the imposture, and she would put her into a

good livelihood for a share in the profits. To make the miracle convincing, she

had been told that she had to produce the same number in a litter as a female

rabbit would deliver, maybe thirteen in all. The introduction and delivery of

all these rabbit parts had caused her great pain and discomfort, she had

simulated some of the pains but the rest had been genuine agony.

|

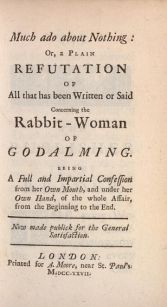

| Several Depositions - 1727 |

At the same

time, Lord Onslow took depositions from six people, who all said that they had

sold rabbits to Joshua Toft. Under a statute of Edward III, Mary Toft was

charged with being a vile cheat and impostor, and sent for a short while to the

Bridewell at Tothill Fields. Great crowds sought entry to see her but none of

the public was admitted; she was attended solely by the gaoler’s wife and

whenever Joshua Toft visited her, he was closely searched before being allowed

into her cell. However, the prosecution was not proceeded with, and Mary

returned home to Godalming.

This wasn’t the end of her criminality – in 1740,

she was served a sentence in Guilford gaol for receiving stolen goods. She died

in January 1763.

The repercussions of the Toft case resounded throughout

Georgian England, and it is these I will turn to next.

Tomorrow - Repercussions and so forth ...