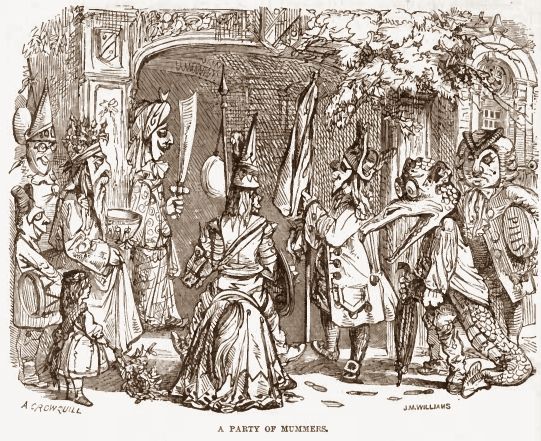

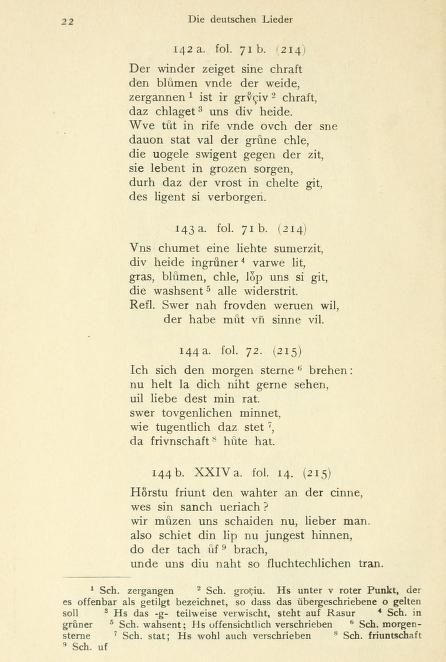

The Puritan Pamphleteer Phillip Stubbes got himself

into a right old lather about his neighbours’ festive amusements and let them know

what he thought about them in the marvellous madness of his Anatomie of

Madness (1583).

“But fpecially in Chriftimas tyme, there is nothing els vfed but cards, dice, tables, mafking, mumming, bowling, & fuch like fooleries.”

Stubbes had a thing about dice in particular and rattled on

about the sinfulness of playing with them ad nauseum, but he didn’t live

to see the dies put away for the last time, (here’s a thing that might win you

a pint in a pub bet – dice is the singular form, the plural is dies).

Dies played a part in the ‘mummerie’ of 1377 I mentioned yesterday, when

the then Prince Richard (later Richard II) was entertained by his future

subjects, as related by John Stow in his Survey of London (1598),

“… the said mummers did salute, showing by a pair of dice upon the table their desire to play with the prince, which they so handled that the prince did always win when he cast them. Then the mummers set to the prince three jewels, one after another, which were a bowl of gold, a cup of gold, and a ring of gold, which the prince won at three casts.”

It’s surprising what you can

get away with if you have a couple of loaded dice and a susceptible Prince to

hand.

|

| Snapdragon |

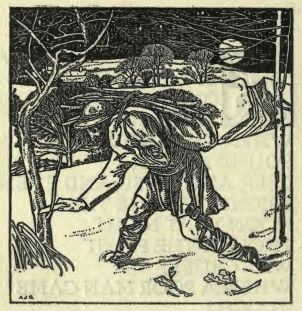

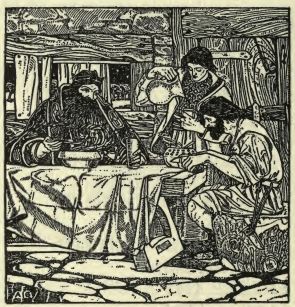

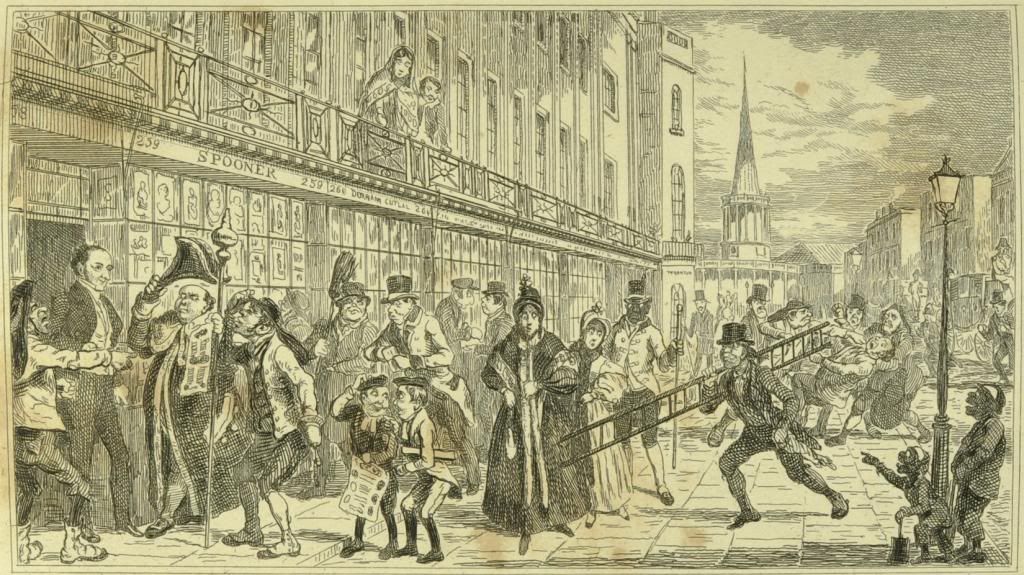

Another Christmas game was Snapdragon, a marvellous pastime that has gone

the way Hot-Cockles, Post and Pair, and the Fool Plough. In the times before

Health and Safety and Political Correction Gone Mad, small children were

encouraged to play with burning brandy, (mix together fire, alcohol and

children - what could possibly go wrong?) in the game of Snapdragon, wherein

currants or raisins (or other fruits and nuts, such as plums, figs, almonds

etc), are put into a bowl, brandy is poured into the bowl and set alight, and

the children each take turns to snatch a blazing fruit from the bowl and pop it into

their mouth, thus extinguishing the flames. It is best played in a darkened

room, when the blue flame of the burning spirit can be seen to finest advantage.

What, I repeat, could possibly go wrong? And yet, this harmless parlour

diversion has passed into history.

|

| Playing Snapdragon |

There was a rhyme to be recited whilst the

game was being played,

“Here he comes with flaming bowl,

Don't he mean to take his toll,

Snip ! Snap ! Dragon!

Take care you don't take too much,

Be not greedy in your clutch,

Snip ! Snap ! Dragon!

With his blue and lapping tongue

Many of you will be stung,

Snip ! Snap ! Dragon!

For he snaps at all that comes

Snatching at his feast of plums,

Snip ! Snap ! Dragon!

But Old Christmas makes him come,

Though he looks so fee ! fa ! fum !

Snip ! Snap ! Dragon!

Don't 'ee fear him, be but bold —

Out he goes, his flames are cold,

Snip ! Snap ! Dragon!”

|

| A Snap-Dragon-Fly |

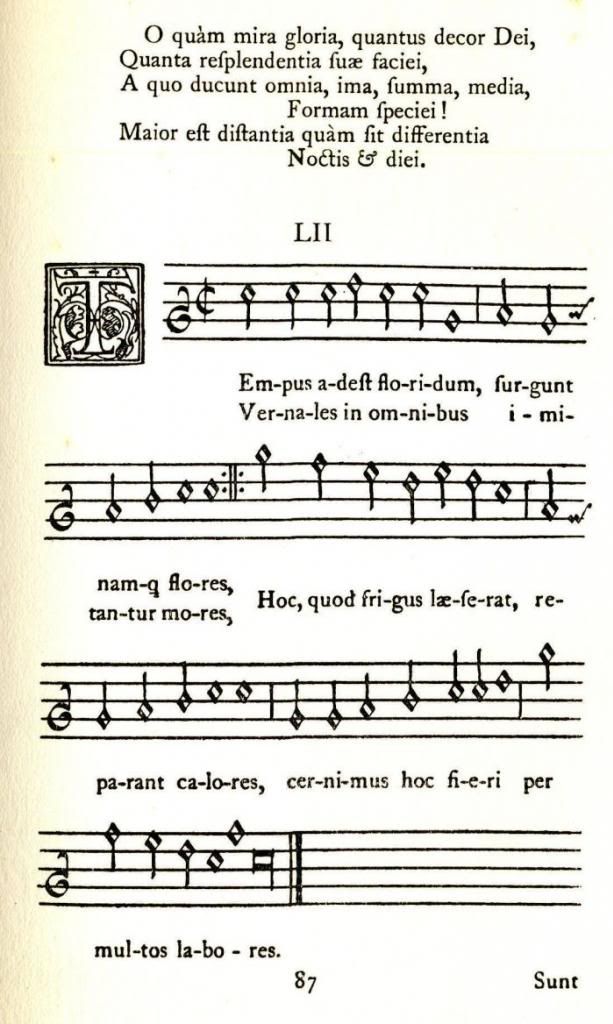

A correspondent to the January 1857 edition of Notes

and Queries speculated that the game took its name from the German words Schnapps

– a spirit, and Drache – dragon, and went on to mention that the game

had also been called flap-dragon and slap-dragon. The same

article also adds quotations from Shakespeare, from The Winter’s Tale,

“But to make an end of the ship: to see how the sea flap-dragoned it,”

Love’s

Labour’s Lost,

“Thou art easier swallowed than a flap-dragon,”

and

the second part of Henry IV,

“And drinks off candles' ends as flap-dragons.”

This last recalls a variation of the game Snapdragon played

by adults, wherein a lighted candle was fixed into a mug of ale or cider and

players had to drink from the flagon with burning their faces or setting fire

to their hair. What larks!

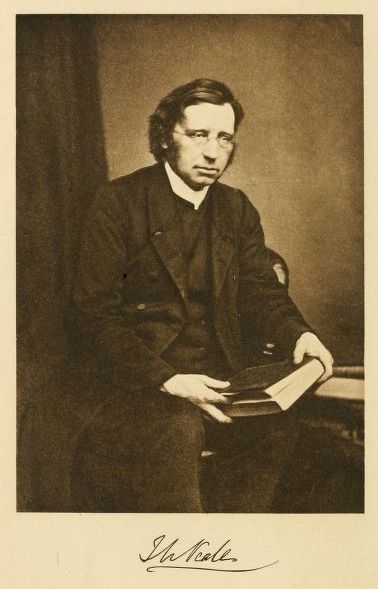

Michael Faraday referred to Snapdragon in his first

Royal Institution Christmas Lecture The Chemical History of a Candle

(1848), suggesting the fruits acted as a wick for the burning spirits, allowing

the burning to take place without consuming the wick.

|

| Michael Faraday - The Chemical History of a Candle |

The Royal Institution

Christmas Lectures are one of this country’s great treasures, begun in 1825 and

given every year since (apart from a wee blip during 1939-42, due to Corporal

Hitler’s Unpleasantness), they are a series of related public lectures on a

single topic, given by a top boffin of the day (David Attenborough, Carl Sagan,

Richard Dawkins, Susan Greenfield, Ian Stewart and Monica Grady spring to mind),

and although aimed at children they are easily interesting enough for an adult

audience. From 1966, they were televised, first of all on BBC2 and they were an

important highpoint of this kid’s Christmas, when a grown-up would tell me

really interesting stuff with a few experiments thrown in for good measure, and

they are one of the things that first got me interested in science (which was

the plan, after all). Things were going along fine until the pencil-squeezers

and the bean-counters who, knowing the price of everything and the value of

nothing, got their grubby fingers in the mix and the lectures were moved to,

firstly, Channel 4 and then, unbelievably, Channel 5 and More4, until their

return in 2010 to the BBC, in a reduced form of three instead of five lectures,

now shown on BBC4, that other marvellous national treasure that broadcasts the

best television in the world. Let’s hope that is the end of the matter and we

can go on enjoying them henceforth.