You know when you listen to a song but you don’t

quite catch the lyrics properly – an example of this was used in an advert for

Maxell audio cassettes a good few years ago when the title line from Desmond

Dekker’s hit Israelites was subtitled as ‘Me ears are alight’.

These mis-hearings are called Mondegreens, a word coined in 1954 by

Sylvia Wright and derived from a seventeenth century ballad, The Bonny Earl

O’Moray, the first verse of which is,

“Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands,Oh, where hae ye been?They hae slain the Earl O' Moray,And laid him on the green.”

Wright wrote that some people have mis-heard that last line as ‘And Lady Mondegreen’,

from which she coined the term for this phenomenon. Another example can be

found in the Christmas song Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, when the line ‘All

of the other reindeer’ becomes ‘Olive, the other reindeer’. When I

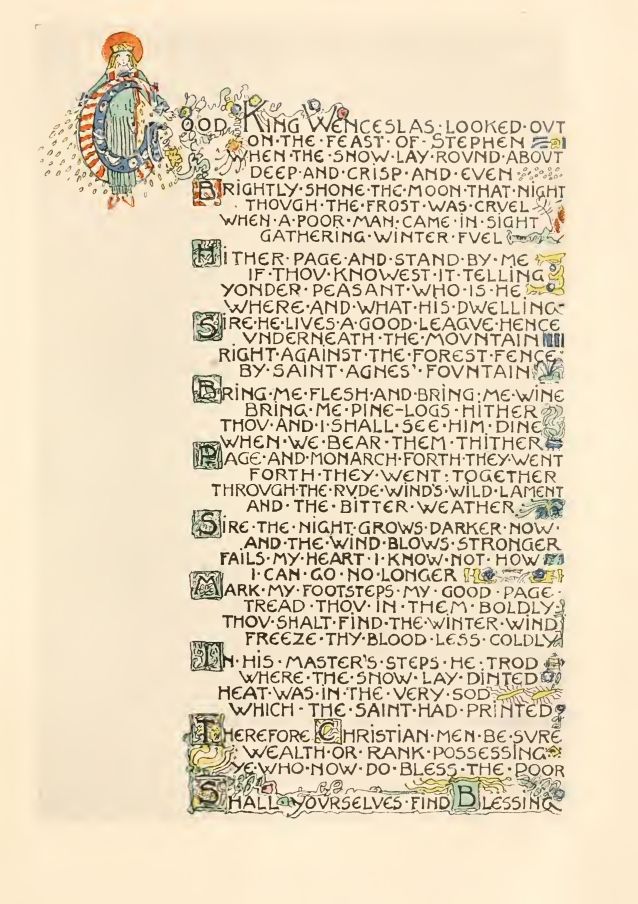

was a boy, my tin ear turned ‘Good King Wenceslas looked out’ into ‘Good

King Wenslass last looked out’, which kind of makes sense if there ever was

a Good King called Wenslass who looked out for a last time, which there wasn’t,

and so it doesn’t. It was just me getting it wrong.

Anyway, Wenceslas did his

looking out on the feast of Stephen, which is feast-day of St Stephen, the

first Christian martyr, held on December 26th, the day after

Christmas Day. Stephen was an early Christian deacon who found himself at odds

with the Jewish authorities not long after the crucifixion of Jesus and was

stoned to death by them for his troubles, with that self-serving opportunist

Saul of Tarsus (who later styled himself Paul) holding their cloaks for them

and looking on whilst they killed Stephen, (I side with the opinion of Thomas

Jefferson, who thought Paul was the first corruptor of the teachings of Jesus.

I have no truck with this Saul or his obnoxious theo-blatherings).

So, who was this

Wenceslas chappie, anyway? Václav I (Václav is Czech, and translates into

English as Wenceslas) was a Bohemian Duke, born in about 907, to Wratislaw (a

Christian Duke) and Drahomira (a tribal pagan), and after his father’s death,

the young Wenceslas was raised and educated by his grandmother, Ludmilla.

Drahomira resented Ludmilla’s influence over her son and arranged to have her

strangled, an act that appalled Wenceslas, who wrested power from Drahomira and

declared himself Duke. He supported the spread of Christianity in his realm and

soon acquired a reputation for personal piety and charity to the poor.

Drahomira plotted with her son Boleslav, Wenceslas’s younger brother and, on

the Feastday of Saints Cosmas and Damian, September 28th 935, as

Wenceslas was making his way to church, he was attacked and killed by three

followers of Boleslav, who then assumed his brother’s title of Duke.

|

| Gathering Winter Fuel |

After his

death, Wenceslas was soon declared to be a martyr and given the posthumous

title of King by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, a cult quickly grew up around

him in both Bohemia and England, and by the eleventh century he was declared

the Patron Saint of Bohemia. In the many hagiographies of his life, there are accounts

of his numerous acts of kindness, generosity and mercy and he was soon regarded

as the model of the Righteous King.

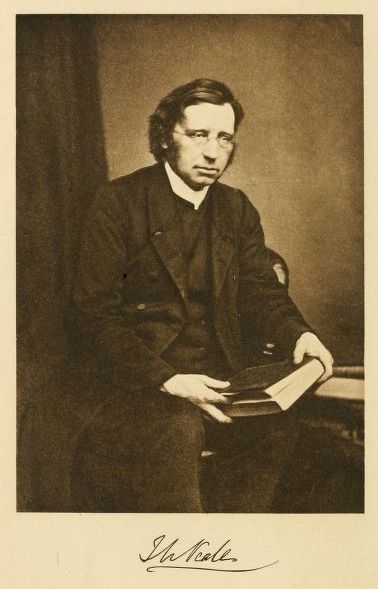

|

| John Mason Neale |

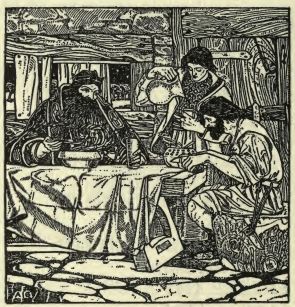

In 1853, John Mason Neale, an English

hymnologist (he also wrote Good Christian Men, Rejoice), published a

carol Good King Wenceslas, which tells how the King went out on St

Stephen’s day to take food, drink and fuel to one of his poor subjects and

encourages his faltering servant to follow in his footsteps in the deep snow.

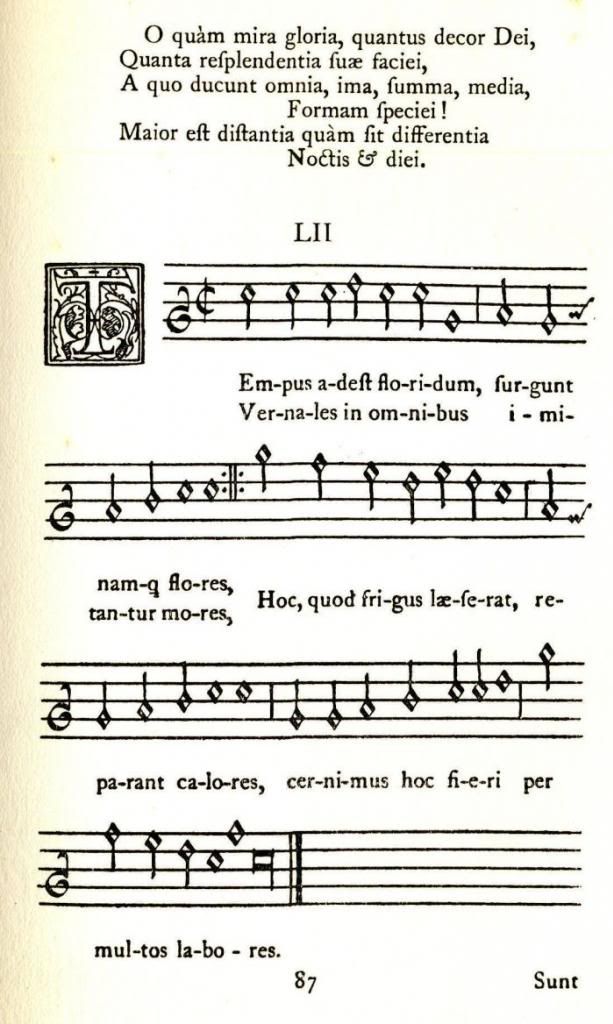

|

| Piae Cantiones - Tempus adest floridum |

Neale took the tune from a thirteenth century spring carol, Tempus Adest

Floridum (Spring has Now Unwrapped the Flowers), published in a rare

(and possibly unique) Finnish song collection Piae Cantiones of 1582, a

copy of which was given to Neale by G J R Gordon, Queen Victoria’s minister in

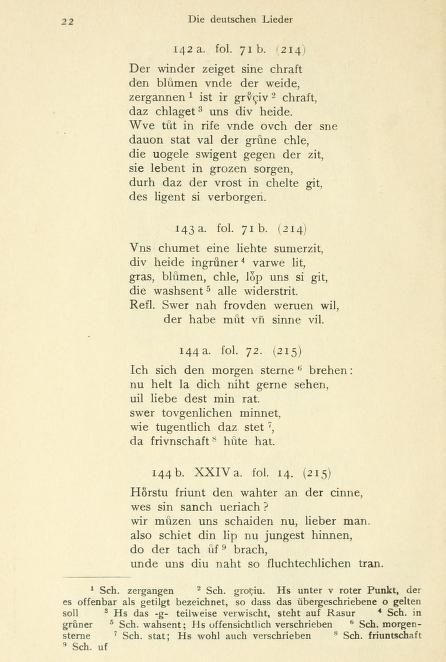

Stockholm, (a verse with a similar beginning can be found in Carmina Burana

(CB 142), although this quickly becomes rather more carnal than spiritual).

|

| Carmina Burana 142 |

The

words are Neale’s translation of a poem by the Czech poet Václav Alois Svoboda,

(and bear no relation to the text of Tempus Adest Floridum); Neale had

been aware of the legend of Wenceslas previously and had included a prose

version of it in his Deeds of Faith (1849), a children’s book about the

deeds of the martyrs.

|

| J M Neale - Deeds of Faith - 1849 |

Good King Wenceslas is now a very popular Christmas

carol, although it has not always been so, as some snooty contemporary

commentators questioned the matching of Neale’s ‘doggerel’ with an

Easter hymn and looked forward to the carol falling into early oblivion. But

fingers had always been pointed at Neale; although he was thought to be the

finest Classical scholar in his year at Cambridge University, he was denied a

First due to his deficiency in mathematics.

|

| Mark My Footsteps, My good page |

He was ordained as an Anglican

priest but was forced to resign a position following arguments with a bishop when

he took a wardenship in East Grinstead. In 1854, Neale co-founded an order of

Anglican nursing nuns, the Society of St Margaret, also at East Grinstead but

came into opposition with some who questioned his High Church affinities,

feeling that he was seeking to undermine the Anglican Church from within and

turn it towards a more Roman Catholic form. Anti-Catholic feeling was running

high in England at the time, and any move towards a more ritualistic system of

worship was viewed with great suspicion.

|

| Thou and I shall see him dine |

Neale’s position wasn’t helped when

one of the young nuns died from an infection of scarlet fever contracted whilst

nursing the sick. Her father believed she had been deliberately placed in

danger by the order, a belief strengthened by her having altered her will after

entering the order and leaving it a sum of money. At her funeral, the father

attempted to disturb the ceremony and a mob gathered around, threatening the

nuns and throwing Neale to the ground. The police were called in and the

situation degenerated into an open riot, with threats made on Neale’s life and

his house being stoned.

Even after the funeral, the nun’s father caused further

trouble in the press and Neale received further threats that his home was to be

burned down. Eventually, the situation eased, not least because of Neale’s

innate goodness, although he continued to be viewed with suspicion and he died,

worn out through hard work, at the young age of forty-eight.

No comments:

Post a Comment