By the turn of the nineteenth century, many of the

traditional English Christmas customs were in decline. Industrialization had

severely affected Public Holidays, as mill and factory owners were opposed to

granting their workers all the usual feast-day holidays. In 1761, the Bank of

England closed for 47 days, which had dropped to 40 in 1825 and to 18 by 1830.

The number of observed holidays fell dramatically to 4 in 1834 and the 1833

Factory Act restricted the legal right of British workers to a mere two days

holiday other than Sundays – Christmas and Good Friday. Other changes in social

and religious practices wore away at the observance of Christmas and many old,

traditional customs had never really recovered from the depredations of the

Puritans in the 1640s and 1650s. Many people were concerned by the losses –

folklorists, historians, poets, musicologists and so forth, and efforts were

made to preserve and perhaps even revive what was being lost, a spirit not

restricted to Christmas. The Oxford Movement campaigned for reforms in the

Church by promoting a return to ritual, decoration and observance of old feast

days, for example.

|

| Charles Dickens |

It is a moot point if Charles Dickens was working within

this zeitgeist or if he was one of the originators of the sentiment, but he was

certainly extremely influential in the promotion of traditional Christmas

customs. In 1843, Dickens toured a Ragged School in London and was greatly

affected by what he saw there and in September of the same year he travelled to

Manchester on a fund-raising event for the Athenaeum, an organisation that was

dedicated to the education of workers. He spoke about the links between poverty

and ignorance, and the germ of an idea was born in his imagination. Dickens had

experienced extreme poverty as a boy and was an active social reformer in his

adult life and, coupled to floundering sales of his serialised novel Martin

Chuzzlewit and needing money as his wife was pregnant, he worked throughout

October and November to write new two episodes of Chuzzlewit and a new

short story with a Christmas theme.

|

| Charles Dickens - A Christmas Carol - 1843 |

A Christmas Carol appeared in late

December 1843, and sold the entire first edition of six thousand copies in five

days. It was an immediate critical success but it was not exactly the financial

godsend that Dickens had hoped for. There was a vogue at the time for ‘coloured

plate’ novels and Dickens followed the fashion, paying for the first edition

himself, a foolscap octavo volume of 160 pages with four hand-coloured plates

and four woodcuts by John Leech, tastefully bound in red cloth, with gilt edged

pages; it sold for five shillings (the equivalent of about £20 today).

|

| Charles Dickens - Title Page - A Christmas Carol - 1843 |

The cost

of production and printing ate into the profits and Dickens only received £230

rather than the £1,000 he had been led to expect. The second and third editions

also sold well, bringing Dickens’s earnings to £726, but it was his first and

last experience with coloured plates.

|

| Scrooge snuffs out the first spirit |

By March 1844, A Christmas Carol

was in its sixth edition and Dickens began to receive appreciative

correspondence from his readers, who told him that they liked to read the work

at family gatherings.

|

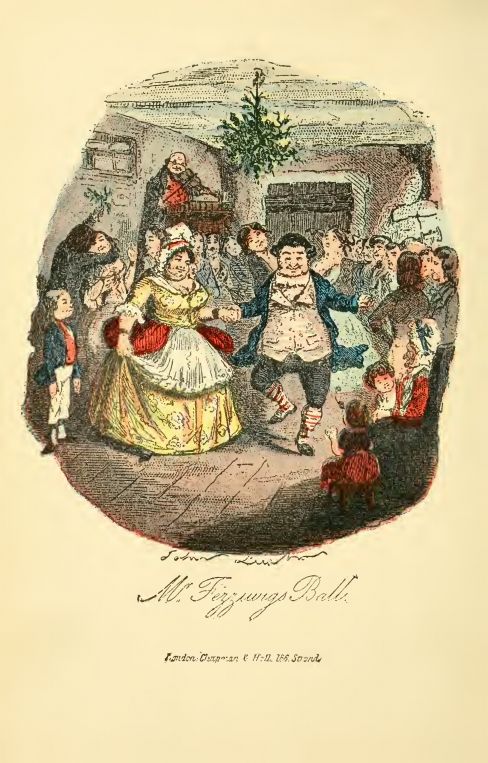

| Mr Fezziwig's Ball |

In December 1853, he read the novel aloud in public at a

charity benefit for the Midland Institute in Birmingham Town Hall and was

afterwards asked by many other charities to repeat the reading. He complied

with the requests but also began public readings for which he charged an

admission fee. He adapted A Christmas Carol into an abridged form, which

he virtually memorised although he kept a copy with him on stage, and which

lasted about two hours, and he later included sections from his other works,

and these readings were a welcome second source of income.

|

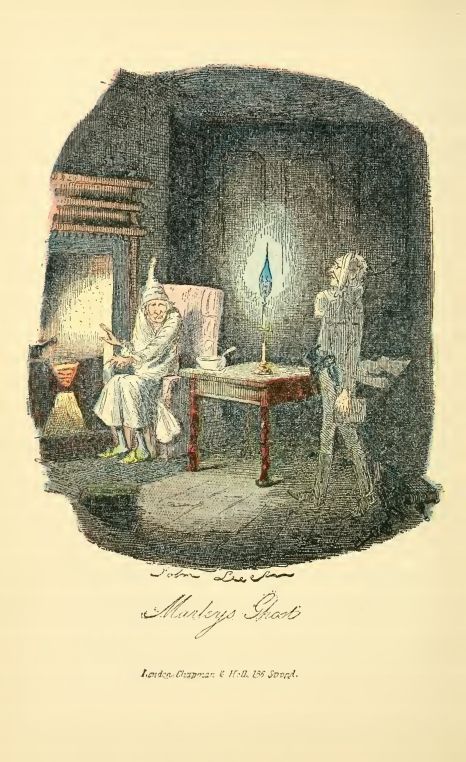

| Marley's Ghost |

He toured America

with a well-received series of public readings and continued with the shows

until March 15th 1870, when he announced that that night’s reading

of A Christmas Carol would be his last – he died three months later.

|

| The Spirits of the Air |

The

plot of the novel is familiar enough, with the characters of Ebenezer Scrooge,

Marley’s ghost, Mr Fezziwig, Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim remaining alive in the

public imagination, but although many readers today see the story as a moral

tale, Dickens was reviving, and contributing to, an English tradition of

Christmas ghost stories – the full title is A Christmas Carol in Prose,

Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, and Dickens encouraged his readers to

approach his book as a ghost story, urging them to read it in a cold room lit

only by a single candle. How can you not feel a shiver from that magnificent

opening line, “Marley was dead: to begin with.”

|

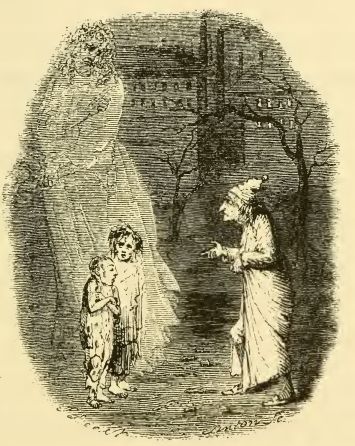

| Ignorance and Want |

That is not to say that

it is not a moral tale – it most assuredly is just that. The ghostly children

that lurk beneath the cloak of the Ghost of Christmas Present are named Ignorance

and Want, in a return to Dickens’s theme of his speech for the Athenaeum

in Manchester. The transformation of Scrooge from selfish miser into charitable

philanthropist stands for the possibility of a transformation of society, where

the haves support the have-nots and employers take an active interest in the

well being of their employees and their families.

|

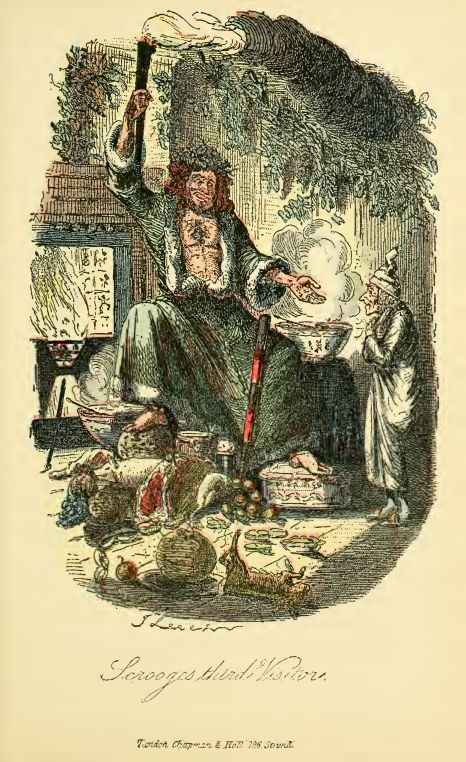

| Scrooge's Third Visitor |

It is in the tradition of

Christian charity, although Dickens himself was not a particularly religious

man and felt that the organised religions of his day were out of touch and not

fulfilling their charitable duties to their fullest extent (fancy that!). He

was criticised in some quarters for not including a more religious element into

the story, Jesus and his birth are not mentioned at all, but the story is about

human charity and the redemption of individuals.

|

| The Last of the Spirits |

Charles Dickens tried to

repeat the success of the 1843 novel in subsequent years, publishing The

Chimes in 1844, The Cricket on the Hearth in 1845, The Battle of

Life in 1846 and The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain in 1848,

but none were as popular as the original and Dickens himself had doubts about

their merit.

|

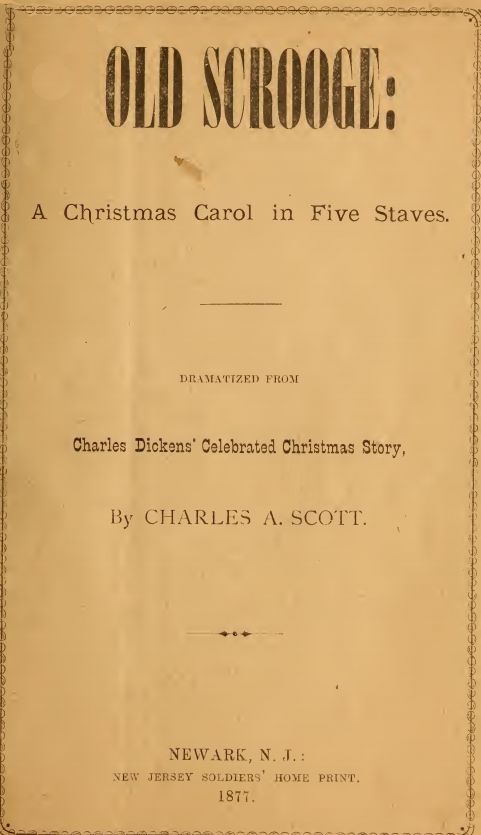

| Old Scrooge - a play inspired by A Christmas Carol |

The story has, of course, inspired numerous adaptations, plays,

readings, films and television versions since but none really catch the spirit

of the original (although the 1951 film Scrooge, with Alastair Sim in

the title role, is perhaps the best film version of any of Dickens’s books and

is a classic in its own right), and the best advice I can offer is that you go

out and buy two copies of A Christmas Carol. Keep one copy and read it

yourself every December and give the other copy to someone you love. And, as

Tiny Tim says, ‘God Bless Us, Every One’.

|

| A Reformed Scrooge and Bob Cratchit |

No comments:

Post a Comment