Waits were one tradition that fell away with time

but the Mummers have remained, although changed, across the years, which is how

it should be. Mumming is a folk tradition and folk traditions need to change if

they are not to turn into museum pieces or self-consciously twee nonsense. The

villages have changed, the villagers have changed, and if the old ways are to

remain alive, vital and relevant, then the folk traditions need to change too.

They are not nice wee performances to entertain smart city dwellers with their

quaint, picturesque, funny country ways; they exist to bring the villagers

together, to give them a common purpose and a feeling of belonging, to let the

young people work with the old people, whereby both can learn to respect the

other and discover their own place in their own community.

|

| Mediaeval Mummers |

They are alive, and

they must grow, develop and change; if they are merely preserved, they will

shrivel and die, as pickled and dry and brittle as a bitter widow, cold and

grudgingly tolerated but ultimately unloved and faintly embarrassing. This is

why Shakespeare scares so many people, as the purists seek to preserve his

works in vinegar but I have seen, for instance, a performance of Macbeth,

performed in a broken old barn on a blasted heath in the middle of winter, done

in modern dress and with solid northern accents, and all before an audience of

a few dozen souls, that was more alive, significant and, damn it, more

entertaining than anything that was ever made by a Hollywood committee with a

budget of mega-millions. I’ve heard ‘better’ folk music sung in the back room

of a village pub by the local postman on his second-hand guitar than I have

when I’ve paid half a week’s wages to sit two hundred yards away from some

bloke who considers himself to be considerably cooler if he wears his

sunglasses indoors.

|

| Mediaeval Mummers |

Anyway, Mumming. There are some people who say the word

goes all the way back to the Greeks, from mommo – μομμο – meaning

‘mask’ and there might well be something in this, although it's more likely that it comes from the old German mummer, meaning 'a disguised person' and vermummen meaning 'to mask one's face, to wear a disguise'. I’ll tell you about

what used to happen in the ancient Greek theatre another time, but the Mummers

plays started, well, nobody knows when, because they are a folk tradition and

things weren’t written down about such things when only the winners bothered

about writing down what they did from one day to the next. Ordinary folk were

far too busy being oppressed to worry about it. Or at least that’s what some

historians would like you to think. Actually, the folk were far too busy

enjoying doing their Mumming to bother about it, and what mattered would be

remembered because it mattered and what wasn’t important would be forgotten

because it didn’t matter, because that’s how their minds worked back then, when

they were alive and living in a tradition.

|

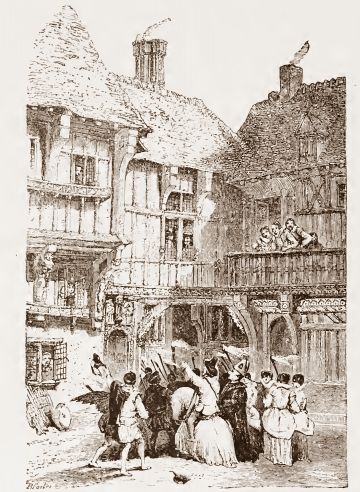

| A Victorian Mummer's Play |

Mummers were Mumming in the Middle

Ages, performing their plays with their set patterns at Christmastide to

audiences in village pubs and in village squares, with locals dressing up as

stock characters in prescribed roles, following the patterns of the plays that

were as old as the oldest old people remembered, turning them and twisting them

to local themes and local concerns, but all the time holding to the overall

feel of the Mumming tradition. The Romans dressed up during Saturnalia,

disguising themselves and getting up to mischief, and this habit continued

after the Empire fell, with ordinary folk dressing up as legendary characters,

mythological figures and such like and performing for their neighbours, often

on Christmas Eve but also at other times of the year.

|

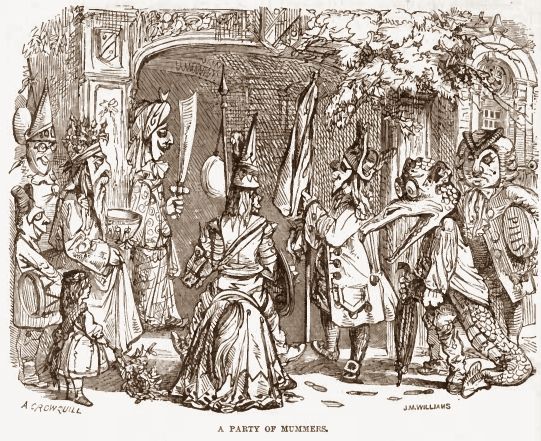

| A Party of Mummers comes to call |

One strand of this

developed into the mediaeval Mystery plays, which were scenes taken from the

Bible and given a folksy English spin, and the other strand became the more

secular Mummer’s plays, which featured such incongruous players as St George,

Achilles, Father Christmas, Judas Iscariot, a Turkish Knight, a Dragon and a

pompous, bumbling Doctor. The plays had a common theme, with (usually) Father

Christmas acting as a narrator, two of the ‘heroic’ figures would fight, amidst

great bluster and mock classicisms, and one would kill the other only to be

brought back to life by the Doctor’s magical physick.

|

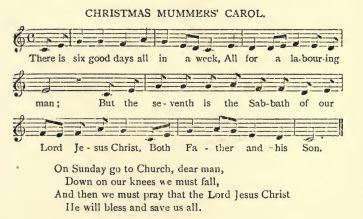

| A Mummers' carol |

The actors (exclusively

male) dressed up in home-made costumes and disguised themselves by, for

instance, wearing masks or blacking their faces with burnt cork, giving us

another name for them, ‘Guisers’, and they were also locally called Geese

Dancers, Pace Eggers and Hobby Horsers. Quite often, the mummers went from

house to house, performing their dramas in return for food, drink or money, and

were a welcome Christmas entertainment for the most part, with their

harum-scarum antics and high cockolorum, although sometimes things turned

decidedly unpleasant when mummers with a long-held grudge exacted their revenge

on an unsuspecting neighbour.

|

| Mummers a-calling |

Indeed, in 1400 a dozen plotters disguised

themselves as mummers in a plot to assassinate King Henry IV, only to be

discovered hours before they could carry out the deed, leading to the customary

hanging, drawing and quartering so beloved by the Lancastrian branch of the

Plantagenets. Ironically, Richard II, who was deposed by cousin Henry, had

enjoyed a splendid ‘mummerie’ held in his honour at London just before

Candlemas 1377, amidst great pageantry and jollity. The mummery of the ordinary

people was enjoyed by other monarchs but were tidied up and polished to become

the Masques of the Tudor and later courts. Henry VIII, when he wasn’t busy

dismantling many of the country’s other ancient establishments, tried to ban

mummery and guising, with anyone who went about in masks, beards or disguises

liable to be arrested as a vagabond, thrown into gaol for three months and

fined at the King’s pleasure but this didn’t check the popularity of mumming

and the plays can still be seen, alive and well, in various towns and villages

at Christmastide across England to this day.

No comments:

Post a Comment