The something else that Lin Zexu did was

unprecedented – he wrote a letter directly to the King of England (who was

actually a woman, Queen Victoria, but he wasn’t to know that). It’s a

remarkable document, written in the traditional ‘memorial’ form, that mixes

highly formalised Confucian language with direct appeals to the monarch’s

humanity and a straightforward account of the facts of the opium traffic.

|

| Lin Zexu |

Lin

drafted and revised his letter, then had English-speaking merchants and

missionaries translate it into English, circulated it amongst the Western

merchants in Canton as a public announcement, and sent a copy off to London. As

it happened, Queen Victoria did not receive Lin’s letter, as it was intercepted

by her ministers, which may be just as well, considering one of the threats it

contained. If the British ruler did not intervene and stop the import of opium

into China, said Lin, then the Chinese Emperor would stop the export of goods

to Britain.

“Has China (we should like to ask) ever yet sent forth a noxious article from its soil? Not to speak of our tea and rhubarb, things which your foreign countries could not exist a single day without, if we of the Central Land were to grudge you what is beneficial, and not to compassionate your wants, then wherewithal could you foreigners manage to exist?”

That’s

right, you’ve read that correctly. Stop sending us your nasty opium or else we

will stop sending you our rhubarb, and you’ll all be dead within a day.

Commissioner Lin certainly knew his stuff. The corrupt western devils were all

constipated and needed the vital rhubarb to maintain their regular lavatorial

habits. Without it, their Empire would collapse, as the population succumbed to

the horrors of bunged-up botties.

|

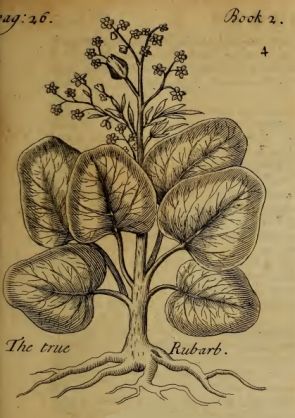

| Pierre Pomet - Rhubarb - in The Compleat History of Druggs - 1737 |

The British simply had to have rhubarb or the

consequences would be too terrible to contemplate – ohh, the straining, the

griping and the moaning. Send us your rhubarb, Commissioner Lin, by all that’s

holy, send us your rhubarb, man.

|

| W J Hooker - Rhubarb - in Medical Botany Vol 4 - 1832 |

The name rhubarb comes from the Greek, ΄Ρā

- Rha - the ancient name of the River Volga, and the medical Latin barbarum

– ‘foreign’, referring to fact that in the ancient world, rhubarb came from the

foreign lands around the Volga.

|

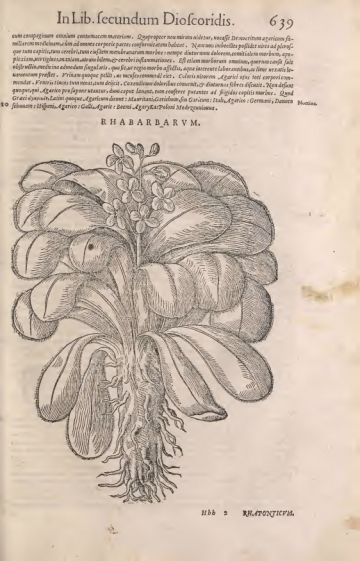

| Petri Andrea - Dioscorides - Rhubarb - in De Materia Medica - 1565 |

Dioscorides, the ancient Greek physician and

botanist, wrote about rhubarb in his De Materia Medica, a first century

pharmacopoeia that was widely used in Europe for over fifteen hundred years (it

was one of the few works from antiquity that was not ‘rediscovered’ during the

Renaissance, as it was never lost).

|

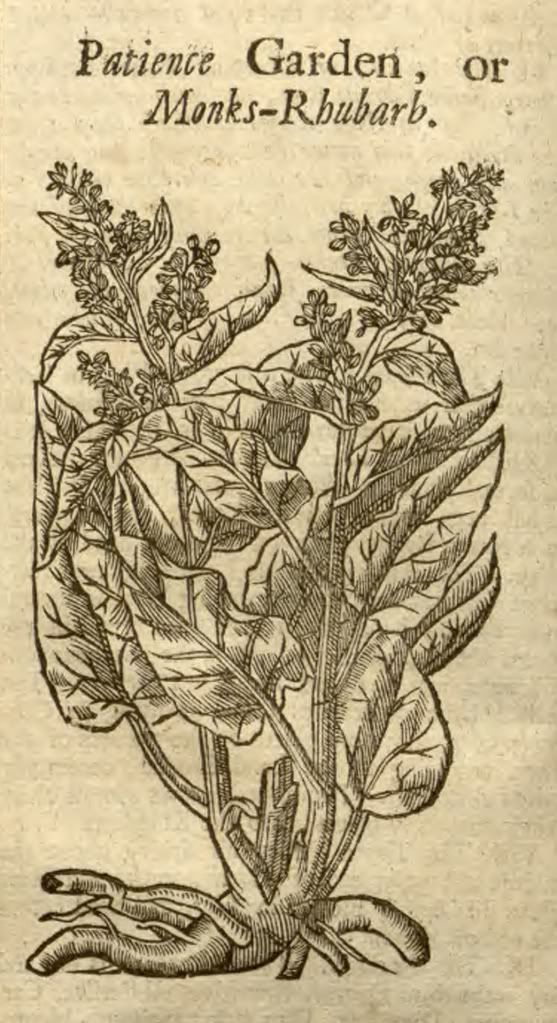

| William Salmon - Rhubarb - in Botanologica - 1710 |

The early explorers who travelled in the

east and to China, including Marco Polo, all make a point of mentioning rhubarb

among the marvels and the treasures that they have discovered; one un-authored

work titled Accounts of Independent Tatary [sic] (1558) records

“Formerly karawans came from Kathay when the way was open. They were nine months on the journey, and brought mufk, rhubarb, fatin, damafk, and other goods”.

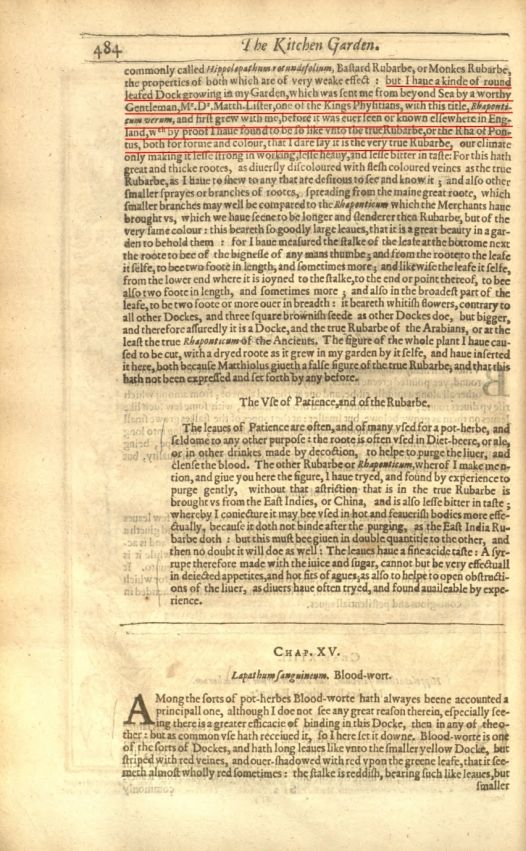

Rhubarb root features in the early herbals, John Gerarde writes,

“It is brought out of the countrie of Sina (commonly called China), which is towarde the east in the upper part of India … it groweth on the sides of the river Rha … as also on the banckes of the river Rha, now called Volga.”

|

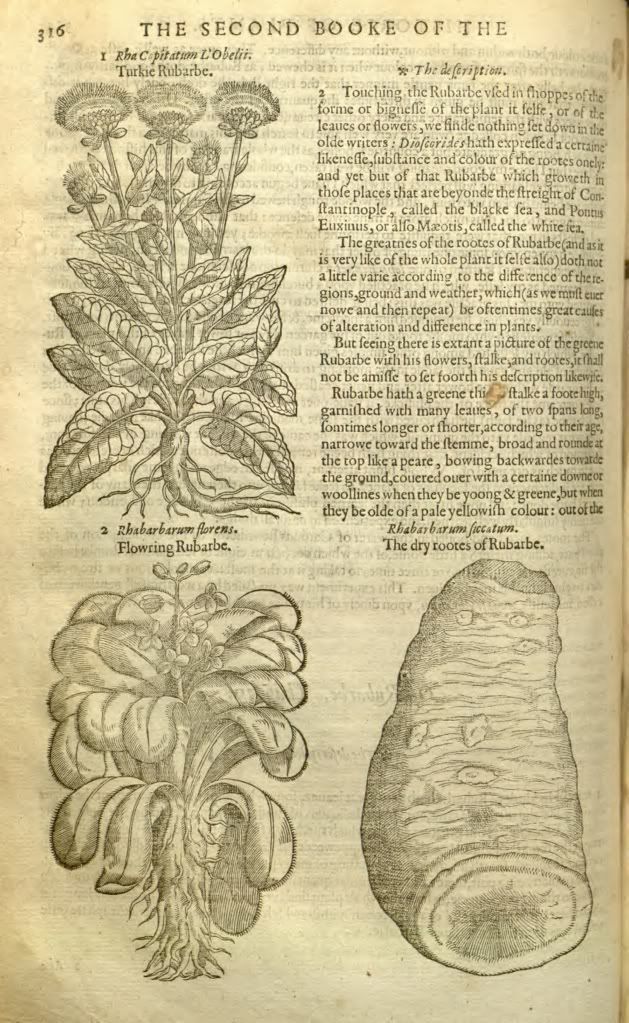

| John Gerarde - Rhubarb - in The Herball - 1597 |

To the

herbalists, there were two rhubarbs – one from Asia, generally called China

rhubarb, and another from a vague area in Asia Minor named Pontus,

which may have been Black Sea, called Turkey (or Turkie) rhubarb

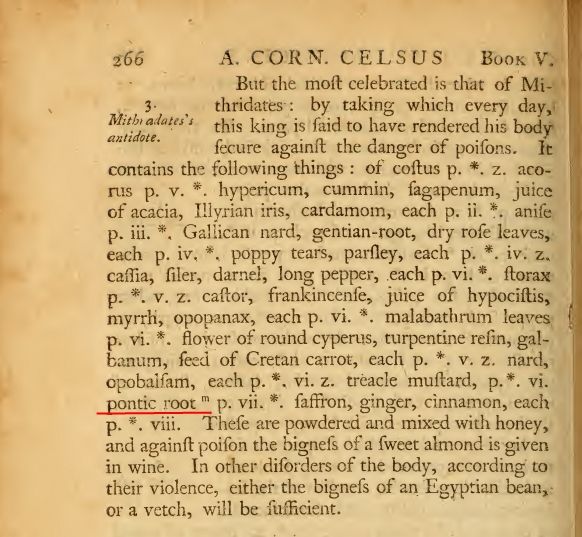

because it was traded through Turkish merchants. This latter was also called Pontic

Root and was an ingredient listed by Celsus in his recipe for Mithradates’s

Antidote, a marvellous medicine said to be even more effective than VeniceTreacle.

|

| Celsus - recipe for Mithradates's Antidote - in Of Medicine - 1765 |

It is important to note that the root of the rhubarb was the medicinal

part of the plant – the stalks (or petioles) that are eaten today were

discarded as unwanted foliage. Men dressed as Turks (or ‘Hindoos’) used

to sell rhubarb root on the streets of London, to be used as a medicine, and in

the early 1800s, a market gardener called Myatt thought that he could grow his own

rhubarb and sell it cheaper than the ‘Turkish’ merchants but he found that his

roots had no medicinal properties.

|

| Dioscorides - De Materia Medica - 1552 |

It is said that one day he happened to chew

one of the young shoots and found it succulent and quite tasty. He made some

tarts with the rhubarb shoots, sweetened with sugar, and was pleased with the

results, but he found it very difficult to sell the stalks at Covent Garden

market. He persevered and eventually rhubarb became a popular filling for pies

and tarts – a correspondent to Notes and Queries wrote that rhubarb pies

were a popular novelty at a girls’ boarding school at Hackney during the 1820s

and 1830s. However, in the History of Esculent Plants, published in

1783, Charles Bryant writes of rhubarb,

“The footftalks of the radical leaves having an acid tafte, and being thick and flefhy, are frequently ufed in the fpring for making of tarts. If they be carefully peeled they will bake very tender, and eat agreeably. Many people prefer them even to Apples.”

Another

correspondent recalled a conversation with the widow of Conrad Loddiges, author

of the Botanical Cabinet, who told him that the Loddiges family were the

first to introduce rhubarb growing to England, although it may be that she is

referring to culinary rhubarb, as medicinal rhubarb is written about by John

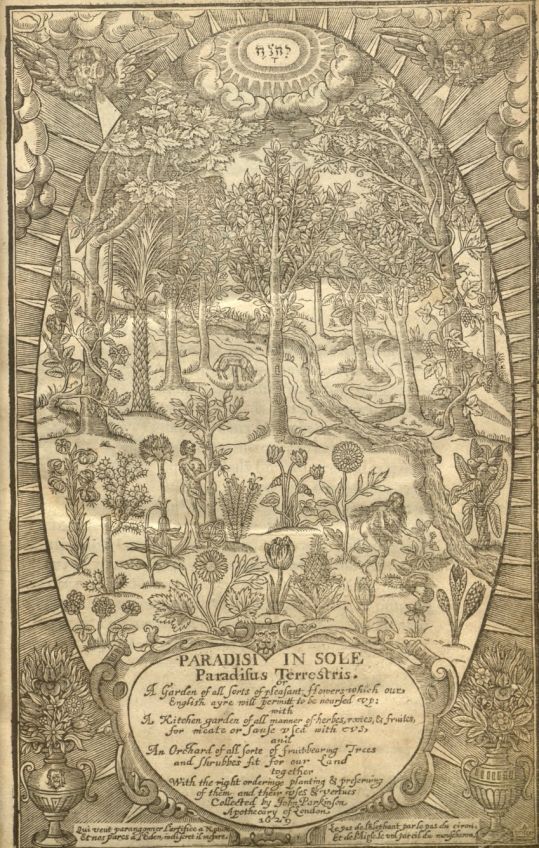

Parkinson in his 1629 herbarium Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris,

|

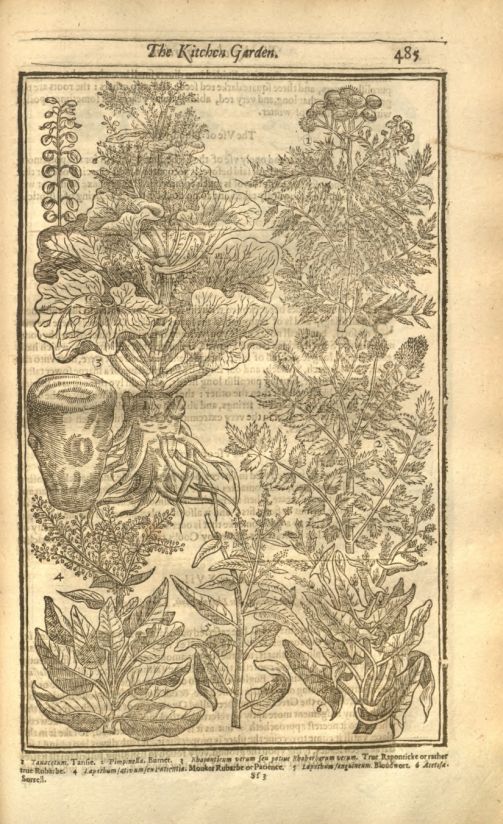

| John Parkinson - Rhubarb (bottom left) - Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris - 1629 |

“… but I haue a kinde of round leafed Dock growing in my Garden, which was fent me from beyond Sea by a worthy Gentleman Mr Dr Matth Lifter, One of the Kings Phyfitians, with this title, Rhaponticum verum, and firft grew with me, before it was euer feen or known elfewhere in England by proof I haue found to be fo like vnto the true Rubarbe,or the Rha of Pontus, both for forme and colour, that I dare fay it is the very true Rubarbe.”

|

| John Parkinson - Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris - 1629 |

But even that may not be the first

rhubarb, in spite of what Parkinson claims, as the eccentric physician Andrew

Boorde added a postscript to a letter to Thomas Cromwell of 1534, in which he

says,

“I haue sentt to your Mastershepp the seeds of reuberbe the which came owtt off Barbary. In thos partes ytt ys had for a grett tresure. The seeds be sowne in March thyn, and when they be rootyd they must be takyn vpp and sett euery one off them a foote or more from another, and well watred, &c.”

Unfortunately, we neither know if Cromwell actually planted the seeds nor if

they grew if he did plant them, but it’s a tantalising thought that rhubarb was

grown here almost five hundred years ago. Rhubarb was widely grown, and eaten,

latterly in England as it is very easy to cultivate and produces its fruit

early in the year (my own rhubarb plant has already started to sprout, at the

beginning of March) but it fell out of favour during and after Corporal

Hitler’s Unpleasantness, when sugar rationing made sweetening rhubarb a lesser

priority for most people.

|

| John Parkinson - Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris - 1629 |

Most gardeners would have had plants however and,

frankly, with little else available people got sick of eating the stuff. When

rationing ended, and when more exotic fruits began to be imported again, the

lowly rhubarb fell from favour although, in recent years, the renewed interest

in old-fashioned ingredients has meant that rhubarb is enjoying something of a

come-back. It is a very versatile foodstuff and works well with such things as

oily fish (mackerel and rhubarb is marvellous) although to my mind rhubarb and

ginger crumble with custard is a food fit for the Gods.

|

| George Chambers - The Tourist's Pocket-Book - 1904 |

A very handy Tourist’s

Pocketbook by George Chambers (1904) has a list of useful medical supplies

that any self-reliant Edwardian traveller should have about them when visiting

foreign parts, amongst which are chlorodyne (a mixture of laudanum, chloroform

and cannabis), quinine, chloroform and rhubarb pills (well, you never know, do

you?).

No comments:

Post a Comment