Miss Mary Blandy continued to introduce the ‘love

philtre’ into her father’s food during the summer of 1751. Her lover,

Cranstoun, wrote a letter to her,

“I am sorry there are such occasions to clean your pebbles. You must make use of the powder to them, by putting it into anything of substance, wherein it will not swim a-top of the water, of which I wrote to you in one of my last. I am afraid it will be too weak to take off their rust, or at least it will take too long a time.”

Mary read between

the lines. She had been putting the powder into her father’s tea but it seems

that it had floated and the old man had been put off from drinking it. That is

why the tea had been left undrunk and why the servants had taken it instead,

although no suspicion arose when they became ill after consuming it.

|

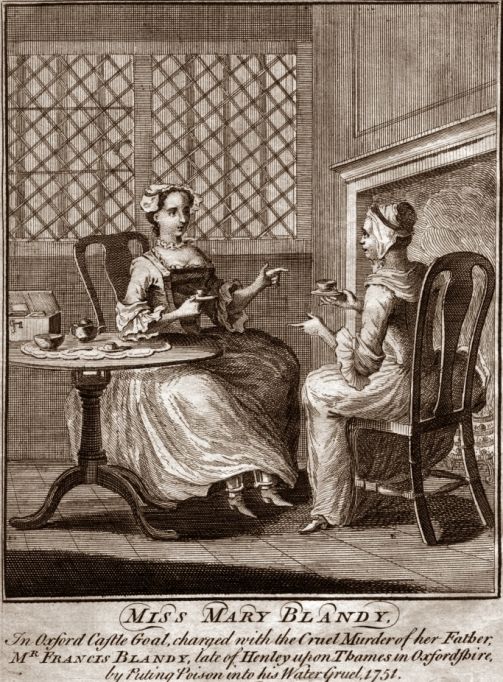

| Miss Mary Blandy |

So, Mary

changed her method – ‘anything of substance’, Cranstoun had said, so she

turned instead to her father’s oatmeal, stirring the powder into his water

gruel. The servants noticed a white residue in the bottom of the gruel pan and

hid the pan away, unwashed. Mr Blandy came into the kitchen one morning, to get

hot water for his shave, and he dropped hints to his daughter that he suspected

a friend of his had been poisoned in the coffee house. His tea, he said, had a bad

taste and he suspected there was something untoward with it.

|

| Miss Molly [sic] Blandy |

Alarmed, Mary went

to her room, took Cranstoun’s letters and the packet containing the powder and

threw them onto the fire. Susan Gunnel, the maid, noticed what was going on and

threw heavy coals onto the fire and when her mistress went out of the room, she

recovered what remained unburned from the hearth, including the packet of

powder. Miss Blandy, in a show of concern, sent for the famous Dr Addington,

who arrived and with typical directness told her that her father was being

poisoned. She denied it, of course, but dashed off a note to Cranstoun,

“DEAR WILLY, My father is so bad that I have only time to tell you that if you do not hear from me soon again, don't be frightened. I am better myself. Lest any accident should happen to your letters be careful what you write. My sincere compliments, I am ever, yours.”

The clerk who was charged with posting this

note handed it over at once to the doctor. The servants produced the gruel pan

and the packet of powder, and Mr Benjamin Norton, an apothecary, confirmed that

love philtre was really white arsenic. Dr Addington pulled no punches. He told

Mary outright,

“If your father dies, you will inevitably be ruined.”

Norton ordered Mary from her father’s bedside and placed Gunnel on watch, with

strict orders to admit no one. Nevertheless, old Mr Blandy asked for his

daughter and when she came, he told her that he suspected Cranstoun of the

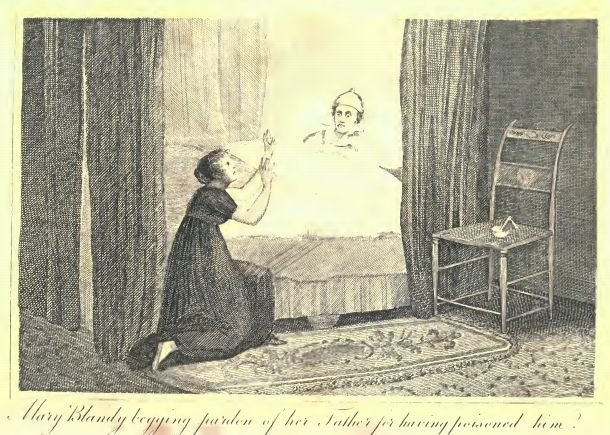

whole sorry business and she could not be to blame. In tears, she begged

forgiveness, and the old man replied,

“I bless thee, and hope that God will bless thee and amend thy life. Go, my dear, go out of my room. Say no more, lest thou shouldst say anything to thy own prejudice.”

Dr Addington asked

Mr Blandy directly whom he thought was to blame for his poisoning,

“A poor love-sick girl, I forgive her. I always thought there was mischief in those cursed Scotch pebbles.”

|

| Miss Blandy begs her Father's Pardon |

It was enough for the shrewd old doctor who took

the law into his own hands and had Mary Blandy put under lock and key in her

own room, with a guard on the door. Sadly, nothing could be done for the old

lawyer and on August 14th, Mr Francis Blandy died in his bed. It

just so happened that the guard placed on Miss Blandy’s door, Mr Herne, had

worked as a humble clerk for her father some years before and who had once had

his aspirations for the hand of the attorney’s daughter politely rejected by

the ladder-climbing lawyer.

Mr Herne abandoned his sentry duty, to go and dig a

grave for his former employer, he said, which convenience gave Miss Blandy the

opportunity to escape into the street and over Henley Bridge. Dressed only in a

half-sack and a petticoat without hoops, she was immediately recognised by her

neighbours and forced to take refuge from the assembling mob in the Angel

tavern. Mr Alderman Fisher, called as a juryman for the inquest and

post-mortem, brought a closed carriage (‘to preserve her from the resentment

of the populace’) to the Angel and persuaded the fugitive to return to her

home with him.

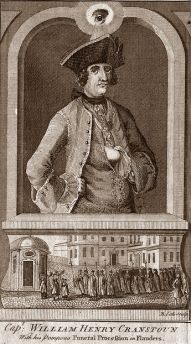

|

| Capt. William Henry Cranstoun |

Later in the day, Dr Addington, assisted by other medical men,

performed the autopsy, and the inquiry concluded that Francis Blandy had been

poisoned and murdered by his daughter, who had administered arsenic to him

concealed in his food and drink. The mayor and coroner issued the constables

with a warrant to detain the prisoner and convey her to Oxford prison to await

the due process of law.

That evening, Mr Francis Blandy was buried, in the

presence of Norton, the apothecary, Littleton, his clerk, and Harman, his

footman; none of his relatives attended. Miss Blandy was given leave to pack

her essentials, including her caddy of fine Hyson tea, and a former servant,

Mrs Dean, was engaged to act as her maid. At four o’clock in the Saturday morning, a landau and four containing the

two ladies and two constables left Henley for Oxford Castle, arriving there at

about eleven.

|

| Miss Mary Blandy takes tea at Oxford Castle |

Miss Blandy was given the finest apartments in the keeper’s

house, where she took tea twice a day, walked in the castle garden’s in the

afternoon and played cards in the evening. Her privacy was respected, and

although great sums of money were offered, no one was allowed to see her

without her permission. In genteel seclusion, she waited for the date of her

trial to be set.

No comments:

Post a Comment