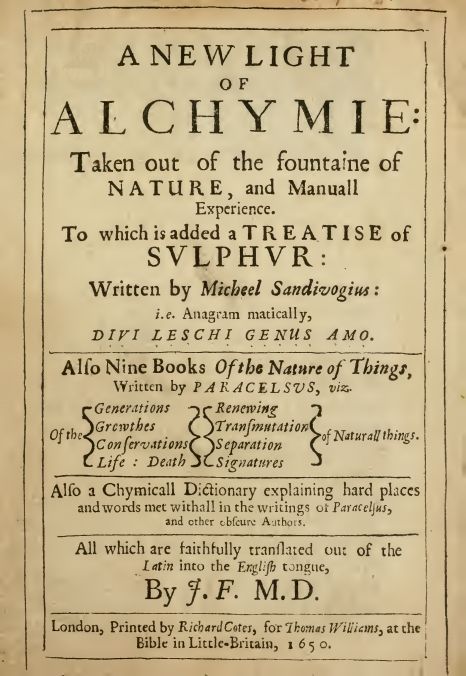

After Paracelsus fled from Basel, he returned to his

earlier peripatetic lifestyle, wandering, seemingly aimlessly, across Europe

and even making his way into Africa. The lies about him, spread by his enemies,

either followed him or were already waiting for him when he arrived at

somewhere new, and he lived a life of low taverns, hired horses and grinding

poverty. He settled briefly at Beratzhausen, on the Danube, and began writing

medical books, but the rancorous, old-school doctors of Leipzig’s Medical Faculty

applied with all ceremony to the Council of Nüremberg to have no more books by

Theophastrus von Hohenheim printed there.

Paracelsus wrote a letter to the

magistrates, which was unsent,

“It is not your business to judge or forbid without careful consideration and discussion: as a matter of fact you are not able to judge of my work, you have not intelligence enough.”

Another letter, which

was sent, said,

“Let those who doubted the truth of his statements meet him in an open Disputation, which, as formerly so now, he would willingly attend.”

|

| Paracelsus |

There was no acknowledgment, only a stony silence, and Paracelsus recorded his

reaction,

“They have forsworn physicians - and God mercifully allows them four – all fools and even horrors.”

He continued to write at Beratzhausen for

almost a year, it mattered little to him where his books were printed, if not

at Nüremberg, then somewhere else would do just as well. His revolutionary

attitude to medicine in some ways reflects the religious upheavals of the

Protestant Reformation that was raging in Northern Europe at the time, although

he objected to being referred to as ‘medicine’s Luther’, however, the

parallels are there, with the attacks on established hierarchies, abused

privilege, misplaced authority and an unquestioning insistence on tradition.

Paracelsus introduced a new way of approaching medicine,

“The power of medicine is to be understood in two ways, in the great world and in man. One way is protective, the other curative. If we protect nature she uses her own science, for without science she would not succeed. But when doctors require to use their science, then are they the healers.”

His attitude was to prevent

illness before it took hold, wherever and whenever possible, by simply living

in a health manner, which included good, fresh food and plenty of fresh air. If

illness did occur, his attitude was to assist the body to heal itself from

within (he called this internal healing force ‘mumia’ which is not to be

confused with the practice of using the remains of mummified bodies as a

medicine, which was popular at the time).

|

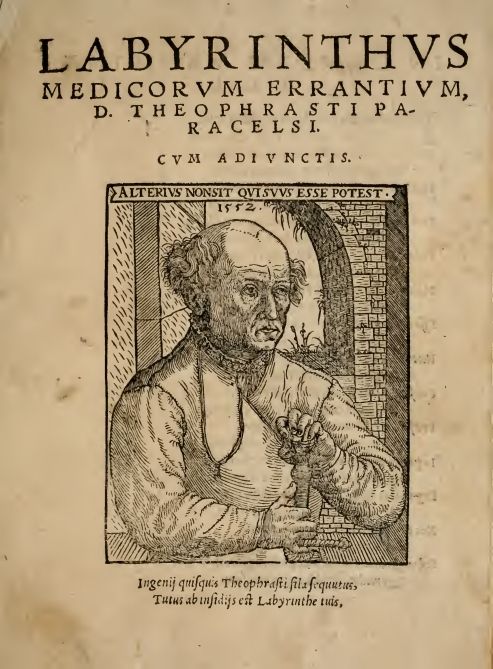

| Paracelsus - Medicina Diastatica or Sympatheticall Mumie - 1653 edition |

His way was the treat the body and

the soul together,

“Rough and harsh are the winds which the truth arouses against its followers, and yet I have ever hoped that He who loves the soul of man loves also his body, that He who saves the soul saves also the body, and therein I have thought to work some little good.”

He is regarded as the

Father of Toxicology and his attitude to poisons follows a similar thread –

“A man may become fat and it is not the fault of his food: or he may become thin and his food does not help him.”

A thing was not, in itself, poisonous,

what mattered was the amount of the dose, too much of anything might prove

fatal if wrongly administered, and even evil could drive out evil, if a poison

was correctly administered as a medicine. Everything was interrelated, part of

whole, and the lesser part mirrored the greater part, microcosm and macrocosm,

God was in nature and nature was God, and all creation was a single entity.

A

part of this philosophy meant that all parts of creation had an effect on one

another, so substances that had not previously considered to be medicinal were

examined, including metals, chemicals and minerals – Paracelsus is credited

with giving the metal zinc its name, seeing the sharpness of the

crystals when smelted, he used the old German word zinke meaning

‘pointed’.

In addition, he pioneered the use of iron, sulphur, mercury, arsenic

and antimony, and he discovered that the alkaloids in opium could be more

effectively dissolved in alcohol rather than water, which he developed a

tincture of opium that he called labdanum, a name that later became laudanum.

Paracelsus had acquired a small quantity of opium in Constantinople and was

rumoured to carry it concealed in the handle of his sword.

|

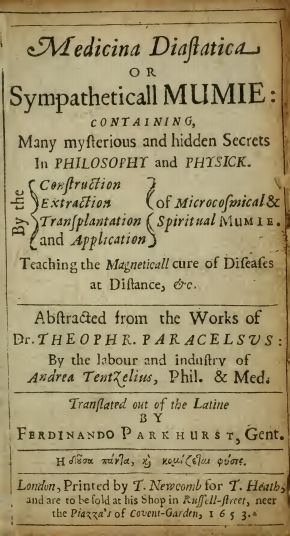

| Paracelsus - A New Light of Alchymie - 1650 edition |

In a near repeat of

the Lichtenfels’ incident, he was called to the bed of Philip, Margrave of

Baden, who was dangerously ill with dysentery, and cured him within days by the

use of laudanum; the grateful Margrave thrust a jewel into Paracelsus’ hand

when he awoke from his stupor but the household staff turned the physician away

without paying the fee, as it was felt that the cure had happened too

quickly. Paracelsus wore the jewel around his neck ever afterwards, as a

protest and token of the outrage (it can be seen clearly in the later portraits

of him).

|

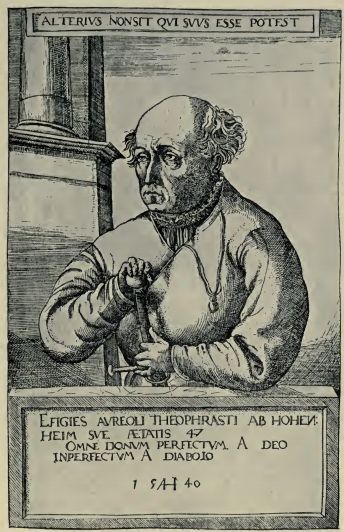

| Paracelsus by Hirschvogel |

One such portrait, by Hirschvogel and dated 1540, also shows the

effects that a lifetime of travel and upheaval, and of decades of working with

poisonous substances; he is drawn, balding and haggard, looking far older than

a man in his late forties. The following year, in September 1541, Paracelsus

died in a room at the White Horse Inn, Salzburg, after making a comprehensive

will and setting his affairs in order. He was forty-seven years old.

Once more, the rumour mills ground out

salacious stories – he had been murdered by an assassin hired by the doctors of

Salzburg, he had been thrown from a rock by a gang of ruffians, he had been

killed with draughts of poisoned wine, ground glass had been put in his beer,

he had been murdered in a drunken bar-fight, and so on and so forth.

|

| Bust of Paracelsus |

The truth

was that he was a remarkable man, a great scholar, a caring and adept doctor, a

pioneering scientist, a prolific author, a hero of humanism, a restless mind in

a restless body and a much maligned individual. If anyone deserves a

re-evaluation and a restored reputation, it surely must be Philippus Aureolus

Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim.

No comments:

Post a Comment