It is a great mistake to imagine the Wars of the

Roses as some latter-day Roses cricket match, with the Red Rose county of

Lancashire and the White Rose county of Yorkshire fighting it out for victory.

The real War of the Roses had little to do with the neat geographical

distinctions between the opponents and everything to do with the noble Houses

of Lancaster and York. In fact, many noble families in Lancashire allied

themselves to the Yorkist faction and, similarly, many Yorkshire families

fought on the Lancastrian side, as England was riven by political, financial

and social in-fighting as the Hundred Years War with France came to an end.

|

| King Edward III |

The

leading contenders for the throne of England came from the Plantagenet Kings,

notably the offspring of Edward III. His son, Edward the Black Prince, died one

year before his father and the crown passed to the Black Prince’s son, who

became King Richard II.

|

| John of Gaunt |

King Edward III’s third son, John of Gaunt, had a son,

Henry Bolingbroke, who eventually deposed his cousin, Richard II, and declared

himself King Henry IV, the first of the Lancastrian Kings of England.

|

| King Henry IV |

His son,

Henry V, carried on the Lancastrian line, and he was followed by his infant

son, Henry VI.

|

| King Henry V |

During, and following, the regency of Henry VI, the Yorkist side

of the Plantagenet family gained influence and power, and Henry was deposed,

twice, by Edward IV, who was the great-grandson of King Edward III. Edward IV

was then followed by his brother, Richard III, who has had his reputation

blackened by later historians.

|

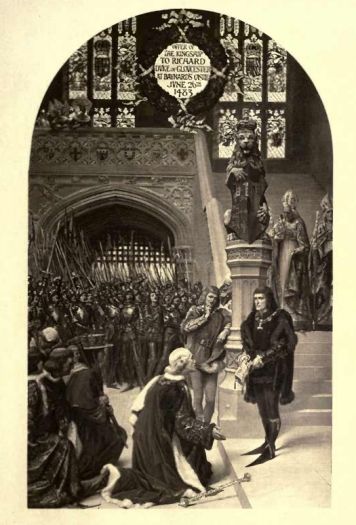

| Richard III accepts the crown |

He is said to have had a hand in the murder of

Henry VI, his brothers Edward IV and George, Duke of Clarence, his nephews King

Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, and numerous others who stood in his way to

the throne. As you will appreciate from all this, the family threads of the

later Plantagenets were very tangled, and just as Richard III thought that he

might form them into a single strand, another distant relative made a bid for

the crown.

|

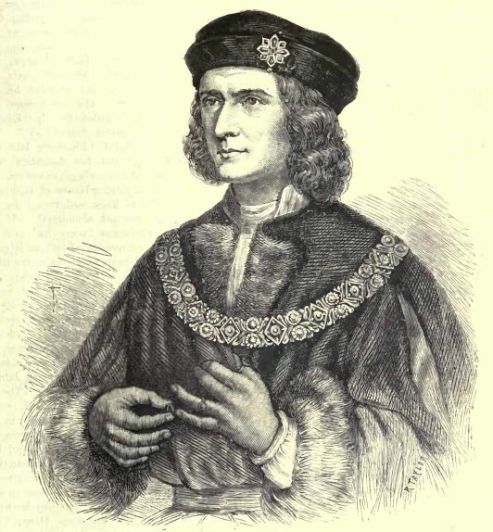

| King Richard III |

Henry of Richmond, was an unlikely contender, his father had died

three months before he was born, his claim came through his mother, Margaret

Beaufort, who was thirteen when he was born, and was a great-granddaughter of

John of Gaunt’s third marriage, by children who had been born out of wedlock

but later legitimised by Richard II, (who had added a clause of doubtful

legality denying that branch of the family any claims of succession). It was a

tenuous, but nonetheless, valid relationship, strengthened a little by links to

the Welsh Tudors. Young Richmond spent most of his life in exile, in France and

Brittany, where his mother, who had remarried into the Yorkist Stanley family,

promoted his claim to the throne.

|

| Elizabeth of York |

In 1483, Richmond was betrothed to Elizabeth

of York, their marriage would unite the Yorkist and Lancastrian lines of the

family. In October, an unsuccessful invasion was planned from Brittany but

terrible weather turned them back. Richard III was aware of the plans against

him and took steps to counter Richmond’s claims, but his own dynastic dreams

received a fatal blow when Edward, his ten year old son, died unexpectedly.

|

| Princes in the Tower |

Richard had had plans for this son Richard to marry Elizabeth of York, daughter

of Edward IV, sister of the Princes in the Tower and his own niece; now he

considered murdering his wife, Anne Neville, (widow of Edward, son of Henry VI)

in order to marry her himself, thus thwarting Richmond’s plans of uniting the

Yorkist and Lancastrian branches of the family.

|

| Sailing for England |

On August 1st 1485,

Richmond and an army of exiles, Scots and French mercenaries sailed from

Harfleur and landed at Mill Bay, near Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, seven days

later. His Welsh family connections brought him support from the Welsh, and

others joined him from the north, as they marched east, through Wales and into

Leicestershire, where Richard was waiting with a massed army (although Stanley

alone did not join him, claiming to be suffering from the sweating sickness).

|

| Richard III rides out |

On August 21st, Richard rode out from Leicester to Bosworth, two

miles away, at the head of 30,000 men, including the finest cavalry in Europe;

Richmond was at Atherstone, his forces barely half the size of Richard’s. Here

he met Stanley, who assured him of support although he could not act at once,

as Richard was holding his son, Lord Strange, as a virtual hostage to ensure

his loyalty.

|

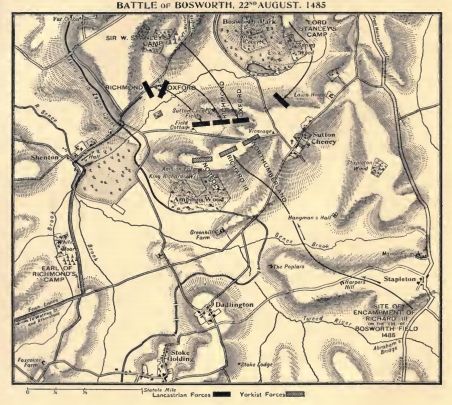

| Plan of Battle of Bosworth |

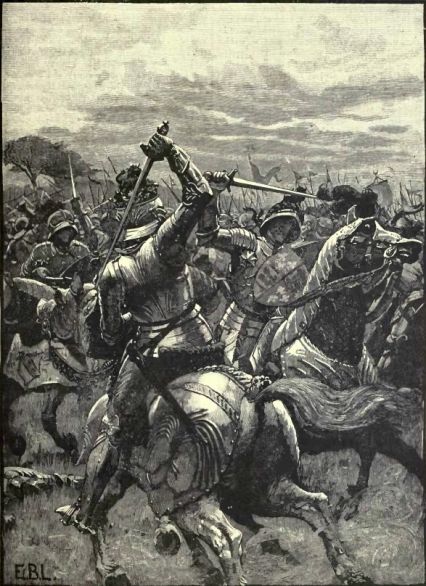

The following day, August 22nd, Richmond and Richard

engaged on Bosworth Field, the battle opening with the archers on each side

firing into their enemy’s troops. Richard led the central body of his army

forward himself, clad in the same burnished armour he had worn at the Battle of

Tewkesbury and wearing a royal circlet on his helmet. He was flanked on each

side by men of the Stanley contingent and these, on a sign, began to attack

Richard’s men.

|

| Battle of Bosworth Field |

Richard, seeing that the Duke of Northumberland was also holding

back, led a direct attack on Richmond’s position; he made three charges in an

attempt to kill Richmond, he killed Richmond’s standard-bearer, Sir William

Brandon, with his own hands, struck Sir John Cheyney from his horse and launched

himself on Richmond himself, when the Stanleys arrived, surrounded him and

hacked him down. He fought, it was said, with tremendous spirit, courage and

strength, distinguishing himself in battle. It was said that the circlet that

Richard wore was hidden in a hawthorn bush by a soldier, but was recovered and

given to Lord Stanley, who crowned Richmond as King Henry VII on the

battlefield of Bosworth Field.

|

| King Henry VII |

Although there followed other, smaller,

engagements (Stoke Field, for example), Bosworth was effectively the final

battle of the War of the Roses.

What happened next to Richard III forms a

fascinating codicil to the story.

No comments:

Post a Comment