When William Kent married Elizabeth Lynes in 1756, it

seemed that he was about to change his former ways. Kent had been a usurer in

Norwich, lending money at high interest, but after his marriage he took, first,

an inn and then a post office in nearby Stoke Ferry, Norfolk. Soon, Elizabeth became

pregnant with their first child and the couple were, by all accounts, happily

married and very much in love.

This domestic idyll was brought to a tragic end

when Elizabeth died during childbirth but her sister, Frances, who had earlier

moved in to help with the birth, stayed on with Kent and the infant boy, acting

as their housekeeper. Kent and Frances, or Fanny as she was known, fell in love

but because the child had been born alive, canon law at the time forbade them

from marrying, even though the baby had only survived his mother by a few

hours.

|

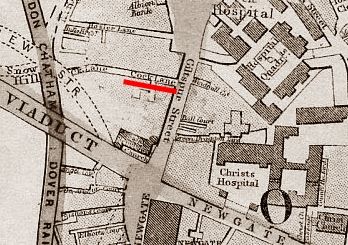

| London - Cock Lane marked in red |

Kent moved to London, hoping that hard work would help him overcome his

grief, but Fanny, her absent heart growing ever fonder, wrote numerous passionate

love letters to him, and she eventually moved to London to be with him. The

pair lived as man and wife, hiding their illicit relationship in the anonymity

of the capital, and they even drew up mutual wills in the other’s favour. The

Lynes family disapproved and frequently intervened, exposing the couple’s

situation to their landlords and forcing them to move lodgings, until at last

they met a sympathetic church clerk called Richard Parsons, who offered them a

room in his house in Cock Lane, near Smithfields meat market.

|

| Close-up of the above map |

It was a tiny house,

just three single rooms, one on each floor, with a winding staircase between

them, in a once-respectable but by then declining area of London. Parsons

himself was also in decline, outwardly respectable but far too fond of drink,

he was struggling to provide for his family, and he borrowed twelve guineas

from Kent, to be repaid at the rate of a guinea a month. Fanny was, by then,

heavily pregnant, and when William Kent went to attend a wedding in the

country, he asked if Parsons’ ten-year-old daughter would stay with Fanny in

their room.

|

| Clerkenwell |

On his return, he found Fanny was ill and, following an argument

with Parsons about money, in January 1760, Kent moved Fanny to more suitable

accommodation in Bartlett Court, Clerkenwell. A doctor was called for, who seemed

sure that the baby was about to be born, but as her condition worsened, he

diagnosed a virulent form of smallpox and told Kent to prepare for the worst.

On February 2nd, after having had her will confirmed as legal by a

solicitor, Fanny died and her body was buried in an unmarked coffin, in the

vaults of St John’s Clerkenwell.

|

| Clerkenwell - St John's marked in red |

Kent was unwilling to put his own name on the

coffin, lest that be seen as illegal, and was unwilling to put any other name

on the casket. He informed Fanny’s sister, Ann, who lived in Pall Mall, of the

death and she attended the funeral, after which Kent offered whichever of

Fanny’s clothing she wanted but Ann declined, adding that she had regarded Kent

and Fanny as a married couple in all but name. However, when Fanny’s will was made

public, the Lynes family were shocked to learn that their sister had left each

of them half a crown with the rest of her estate going to Kent. It wasn’t much,

just over a hundred pounds, and Kent’s own fortune amounted to many times that

amount but still the Lynes felt hard done by and took the case to court, which

found in Kent’s favour, causing more resentment from the family. It seemed that

that was the end of the matter – Kent remarried the following year and took a

job as a stockbroker in London, and sued Parsons for the outstanding debt.

|

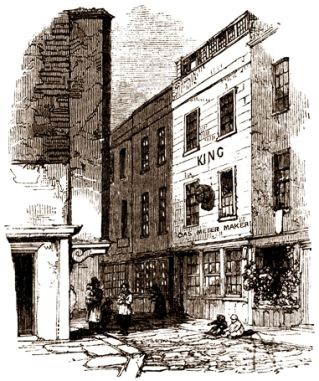

| The House in Cock Lane |

Then, in January 1762, a report appeared in the London Ledger that a

ghostly disturbance had occurred in Cock Lane, at the house of the clerk of St

Sepulchre’s, and an investigation by four gentlemen, including a clergyman, had

revealed that the noisy spirit had rapped thirty-one times when asked if anyone

had been poisoned in the house. Reports from the neighbourhood said that a

woman had been poisoned by her brother-in-law and that her body had been

interred in St John’s Clerkenwell. Other London newspapers took up the matter

during the next fortnight, although any of the names of those involved were

redacted and they were referred to only by their initials. These accounts told

the story that the ghostly rappings had first occurred two years before, when

the dead woman was still alive and had shared her room with the clerk’s young

daughter when her husband was away at a wedding.

|

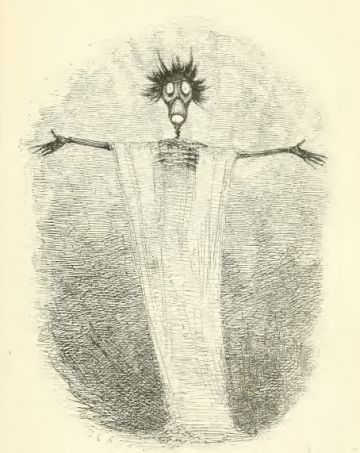

| The Ghost |

There had been knockings and

scratchings, a ghostly figure in white had been seen on the staircase by

several people, and the woman became convinced that it was the spirit of her

dead sister, come to warn her of her own impending murder. Aided by John Moore,

former assistant preacher at St Sepulchre’s and now rector at St

Bartholemew-the-Great, Smithfield, Richard Parsons set about investigating his

daughter Elizabeth’s bedroom, as the sounds occurred when only Elizabeth, now

aged twelve, was present.

|

| Modern Cock Lane |

Noises like the scratching of a cat on a cane chair

were heard, and when questions were put to the ghost, replies were made by one

knock for ‘yes’ and two knocks for ‘no’. Understandably, when William Kent

heard about this, he made straight for Cock Lane and took part in one of the

séances. Things did not go well.

“Are you Miss Fanny ?” ‘One knock - Yes.’‘Did you die naturally?’ ‘Two knocks - No.’‘Did you die by poison?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’‘Do you know what kind of poison it was?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’‘Was it arsenic?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’‘Was it given to you by any person other than Mr. Kent?’ ‘Two knocks – No.’‘Do you wish that he be hanged?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’‘Was it given to you in gruel?’ ‘Two knocks – No.’‘In beer?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’(Here a spectator interrupted with the remark that the deceased was never known to drink beer, but had been fond of purl, [a mix of ale and gin] and the question was hastily put.)‘Was it not in purl?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’‘How long did you live after taking it?’ ‘Three knocks, held to mean three hours.’‘Did Carrots (her maid) know of your being poisoned?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’‘Did you tell her?’ ‘One knock - Yes.’‘How long was it after you took it before you told her?’ ‘One knock, for one hour.’Kent, by now outraged, cried out,“Thou art a lying spirit, thou are not the ghost of my Fanny. She would never have said any such thing.”

Tomorrow - Scratching Fanny in Cock Lane

No comments:

Post a Comment