I bought a new gooseberry bush for my back garden

the other day and I’ve been thinking about the name. There are plenty of plants

that take their names from those of birds – Duckweed, Cuckoo Pint, Chickweed,

Guinea-flower, Crane’s Bill to name but a few, so is the name simply taken from

the bird? If so, why goose, of all things? There is no immediate physical

resemblance between any part of the goose and any part of the plant.

|

| Goose ? |

Geese

don’t particularly favour the plant as a food over any other plant – if anything,

the spines of the plants are more likely to discourage the birds from eating

them. What about eating gooseberries with goose meat? Gooseberry sauce is

very good with fatty and oily foods, and geese are certainly fatty fowls. John

Timbs, in Nooks and Corners of English Life (1867), seems to think so,

as he says,

“Roasted geese were stuffed with gooseberries—hence the term.”

|

| Mackerel ? |

And the French name for the gooseberry, groseille à macqueraux,

would seem to fit

with this, as gooseberry sauce is delicious with an oily fish like mackerel,

but that name comes from the similarity of the stripy fishes to the stripes on

the berries, so maybe this is a dead end.

Perhaps the name is a variant on gorse-berry,

as the gorse is another thorny plant, and doesn’t Shakespeare, in The

Tempest, mention, “Tooth'd briers, sharp furzes, pricking goss, and

thorns.” There may be something in this. A northern English folk-name for

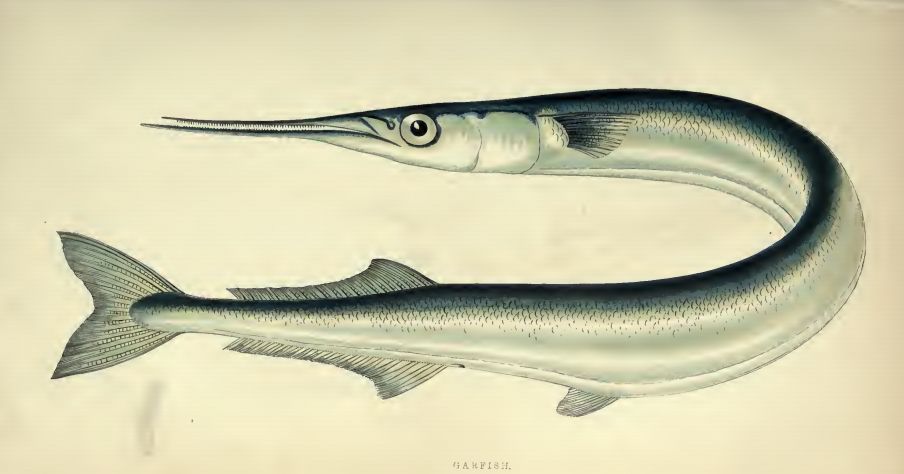

gooseberry is car-berry, which comes from the Norse gar – ‘a

spike or spine’ (as in garfish).

|

| Garfish |

How

about other languages? The German name for gooseberry is krausbeere, ‘curly,

frizzy berry’, in Dutch kruisbes ‘bristly berry’, and the Latin name of

the plant Ribes Uva-Crispa seems to confirm that the name comes from a

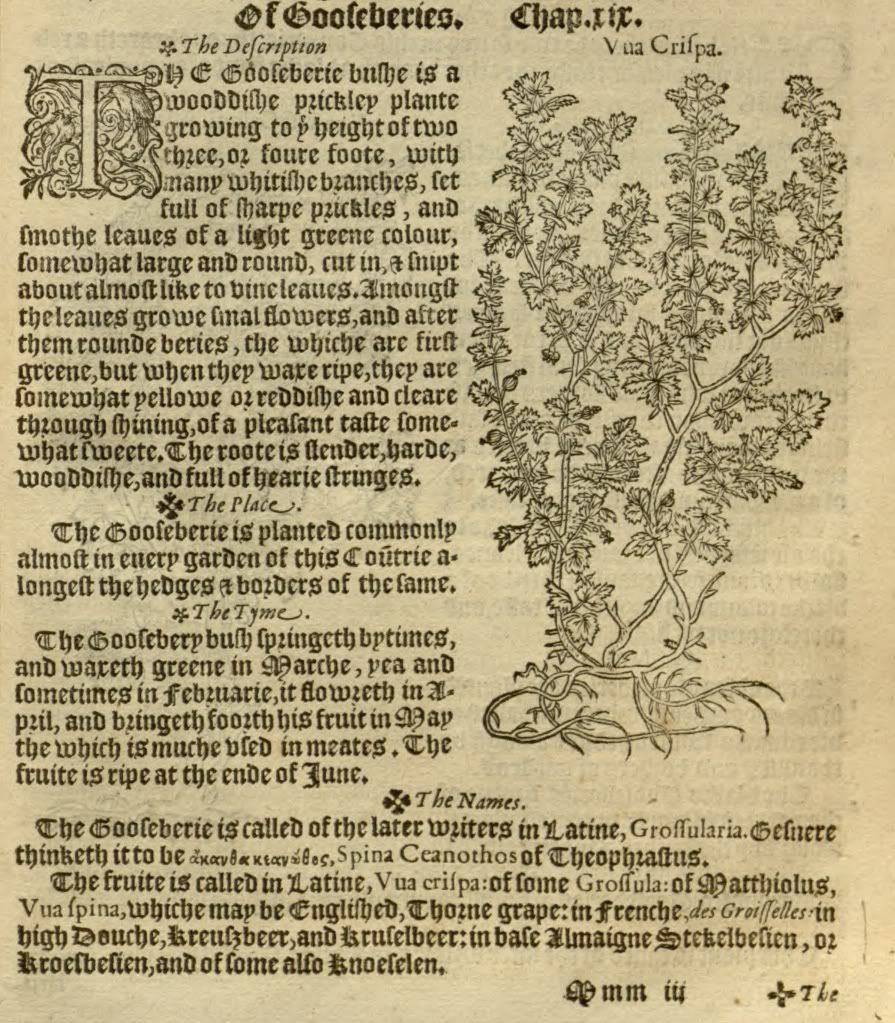

variation of bristle-berry. In the Nievve Herbal or Historie of

Plants (1578), Rembert Dodoens says that,

“The Gooseberie is planted commonly almost in every garden in this Countrie,”

which shows how popular

the plant was, even almost five hundred years ago.

|

| Rembert Dodoens - Goofeberies - from Nievve Herbal - 1578 |

Similarly, Thomas Tusser, writing during the reign of Henry VIII,

in his husbandry hints for September, writes,

“The Barbery, Respis, [i.e. Raspberry] and Goosebery too,Looke now to be planted as other things dooThe Goosebery, Respis, and Roses, al three,With Strawberies vnder them trimly agree.”

|

| Gooseberries |

The gooseberry was used in a wide variety of foods, one of

the most popular of which was Gooseberry Fool. A folk etymology of the name

says that the ‘fool’ is allied to the word ‘trifle’, meaning something light or

of little concern, and although gooseberries are mixed with cream and sugar to

make a fool, rather like a syllabub or custard, the ‘fool’ part of the

name comes from the French fouler – ‘to crush or tread’, as the berries

are crushed before mixing them with the rest of the ingredients.

Another use

for the fruit is for making wine, commonly called Gooseberry Champagne, as the

light white wine is best when made into a sparkling drink (elderflowers can be

mixed with the gooseberries – or elderflower champagne is another delicious

country wine).

|

| Gooseberry |

Playing Old Gooseberry was just another old way of saying

Playing Old Dickens, Playing the Deuce or Playing the Devil, which is to say,

creating havoc. One version of the derivation is that it comes from bottles of

gooseberry wine, stored in a cellar, which shattered when they got warm in the

summer’s heat and exploded, one setting off the rest, and making a real mess.

Playing the Gooseberry also refers to a third person who accompanies a courting

couple, ostensibly acting as a chaperon, and by extension, anyone present whom

others wish wasn’t there. A bit like a wallflower, but fruitier.

|

| Gooseberry |

And, of

course, there are gooseberry pies and gooseberry tarts. What’s the difference?

Well, to my mind, a tart is an open fruit pie (and nothing to do with the

sharp, tart, taste of the filling), whereas a pie has a pastry lid on the top.

In the old days, hand-raised, hot-water pastry crusts were filled with young

gooseberries (older, larger ones would burst and reduce to mush; younger ones

hold their shape), in the same way that hand-raised pork pies are still made.

|

| Gooseberries |

Speaking of larger berries, Charles Darwin, in On the Origin of Species

(1859), mentions how horticulturists were, in his day, selectively breeding

plants that were yielding larger and larger fruits, “… the steadily-increasing

size of the common gooseberry may be quoted,” and, especially in

Lancashire, there were competitions amongst gardeners to see who could grow the

biggest single gooseberry, (the trick is to choose a single berry, which is

grown inside a closed box, with all the rest of the berries removed from the

plant), in the same manner that champion leeks are grown, for example, in the

north east of England. What we call the ‘silly season’ in our newspapers, when

news is slow and stories about almost anything are printed, in Victorian times,

was called the ‘Big Gooseberry Season’.

|

| Under a Gooseberry Bush |

You can’t mention gooseberries without

mentioning babies being found under the gooseberry bush. It was a simple, safe

answer in the past to that question the parents of young children still

continue to dread, ‘Where do babies come from?’ and a handy alternative

to the answer, ‘A stork brings them.’ In Victorian times, little girls

were told they came from the parsley patch and little boys came from the nettle

patch, in a nice addition to the ‘Sugar and spice and all things nice/Slugs

and snails and puppy dogs’ tails’ distinction off what little girls/boys

are made of. Parsley, nettle, gooseberry or cabbage patches, it shuts the

inquisitive little brats up and, by the way, has absolutely nothing to do with

euphemisms for pubic hair, regardless of what you might read on the internet.

No comments:

Post a Comment