Poppies have been used in Chinese medicine since the

seventh century CE, they are mentioned in a pharmacopoeia by Liu Han, Ma Chih

and others, where the seeds of the poppy – ying-tzŭ-su – are described

as being useful for those who have been taking mercury in the belief that it

imparts immortality, if the seeds are mixed with bamboo juice boiled into

gruel. Wang Hsi, who died in 1488, wrote,

“Opium is produced in Arabia from a Poppy with a red flower … the capsule, while still fresh, is pricked for the juice.”

|

| Opium Poppies |

In the latter years of the Ming dynasty, in the seventeenth

century, Spanish and Dutch merchants introduced tobacco from the Americas into

China through the Philippines, and the practice of smoking a mixture of opium

and tobacco began. Edicts against tobacco smoking were issued, but the habit

spread too rapidly to be effectively restricted by law. The Chinese habit was

to smoke their tobacco in pipes, and it spread throughout the entire country,

across all classes and was enjoyed by men and women alike.

|

| Chinese Opium Smokers |

It was not until

1729 that the first edict restricting the use of opium was issued, but this was

also ineffectual, due to the widespread use of the drug, not least amongst

those in positions of power. The punishments were not inflicted on the smokers,

but on anyone involved in the sale and distribution, and were very harsh

indeed. The sellers were imprisoned for several months and then strangled,

their assistants were beaten with one hundred blows and subjected to a

banishment of one thousand miles.

|

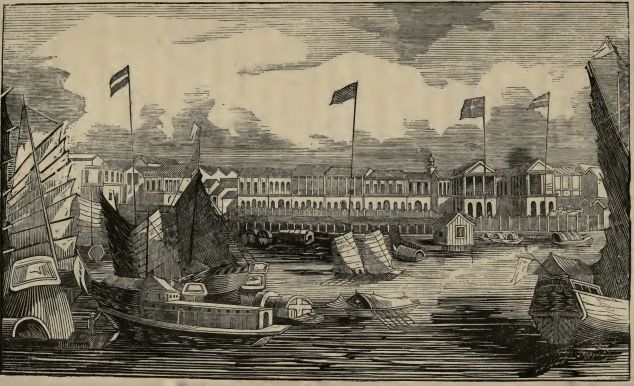

| Chinese Merchants |

Runners, magistrates, police, boat-keepers,

indeed anyone bar the smoker (who, it was felt, had suffered enough with their

addiction), were all severely dealt with, as it was attempted to remove the

scourge from China. In a report to the British parliament of 1783, it was

reported that any vessel caught importing opium to be used for smoking would be

confiscated, the opium would be destroyed and any Chinese members of the crew

would be executed.

|

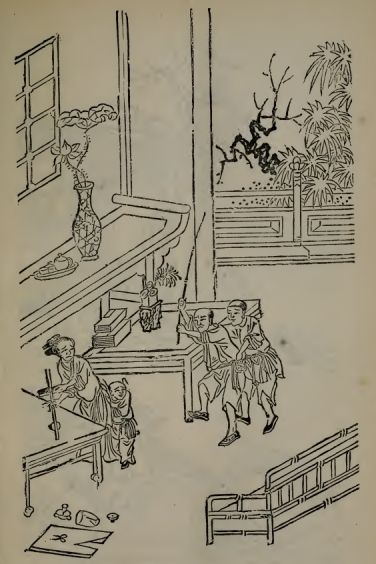

| A Wife tries to destroy an opium smoker's pipe |

Nevertheless, contraband opium continued to be smuggled into

the country and as more opium entered the market, more addicts were created,

and more addicts meant further opium was needed to feed their habit, resulting

in a terrible self-replicating circle. The main reason for the failure of the

official policy was the great number of corrupt of Viceroys, Governors, Customs

Officers and so forth, who were far to easy to bribe, either with silver or

even with opium itself, compounding the problem still further. It is estimated

that Dutch and Portuguese traders were importing no more than two hundred

chests of opium per year at the time, and the edict was intended to stop the

smoking of opium, rather than restricting its import for medical use.

|

| Canton |

In 1773,

the Dutch trade ended and English merchants, trading from Calcutta, took over

the importing of opium into China, until the East India Company in turn took

over the trade in 1781, and by 1790 the imports had risen to four thousand

chests per year. As the smoking of opium spread throughout southern China, the

Jiaqing Emperor issued an edict banning its importation and smoking, together

with the cultivation of poppies, and opium became a contraband cargo.

|

| The Great Wall over the Hills |

The

British, trading through the East India Company, bought vast amounts of goods

from China, including tea and porcelain, for which they paid in silver but the

Chinese imported very few goods from the west, resulting on a drain in hard

currency from Europe.

|

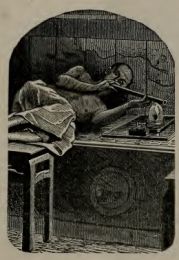

| Smoking Opium |

The opium trade reversed this situation, as silver began

to ooze out of China, to the consternation of the Emperor, who needed funds to

suppress internal revolts in his realm. British vessels shipped the opium to

Lintin Island, where it was unload and the ships proceeded into Canton with

their legitimate cargoes, whilst smaller native vessels smuggled the prohibited

drug ashore later. It was a cash trade on an open market, and demand continued

to grow, from an average of about five thousand chests in the 1810s, which had

doubled by the following decade.

|

| Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu |

From 1820 on, the new Dauguang Emperor issued

many more edicts banning opium and sent his Commissioner Lin Zexu south, to

enforce the edicts. Lin arrived in Canton (now Guangdong) in March 1839 and had

an immediate effect. He was an tremendously efficient bureaucrat and

administrator, and was noted for his honesty and morality, and he confiscated

over 20,000 chests of opium (over one million kilograms) which he had

destroyed, arrested over 1,700 opium dealers, and seized over 70,000 opium

pipes.

|

| Crates of Opium awaiting destruction |

But Lin Zexu did something else in his attempt to stamp out the opium

trade. I will tell you what that was tomorrow.

No comments:

Post a Comment