When you read about the extent of substance abuse in

Victorian Britain, you could be forgiven for wondering how the British Empire

ever became a going-concern in the first place. Those people who did not spend

their days in a drunken stupor busied themselves instead with smoking,

drinking, inhaling, ingesting or injecting themselves with just about any

narcotic concoction that became available to them.

|

| Queen Victoria |

Take Queen Victoria herself

as an example – it is on record that she used chloroform during the birth of her

eighth child, Prince Leopold, in 1853, and it was so ‘delightful beyond

measure’ that it was also used at the birth of her next, and last, child,

Princess Beatrice, in 1857. The use of analgesics during childbirth was unusual

at the time – good Christian women were expected to suffer during delivery

(hadn’t God, after all, said to Eve,

“In pain thou shalt bring forth children”[Genesis 3:16])

- and

Victoria’s decision to use the new anaesthetic was an unexpected move. Her

favourite tipple was single malt Royal Lochnagar whisky mixed with fine claret,

a combination that even the most seasoned of topers would think twice about

tackling on a regular basis.

|

| White and Black Poppies |

We know that she suffered from menstrual cramps

and in A System of Medicine, edited by her personal physician, Sir John

Russell Reynolds, the remedies given are ether, lavender, henbane and cannabis

indica, together with morphia suppositories, and there is every chance that he

would have prescribed some permutation of these options for her Majesty’s monthlies,

and like any other Victorian, she also would have used laudanum for pain

relief, as was the norm back then. That is an important point. There were not

the same restrictions on these substances that are in place today, and a

Victorian would think no more of resorting to laudanum or morphine, as we would

think of turning to paracetamol or ibuprofen to ease that persistent ache that

bothers us.

|

| Dr Collis Browne's Chlorodyne |

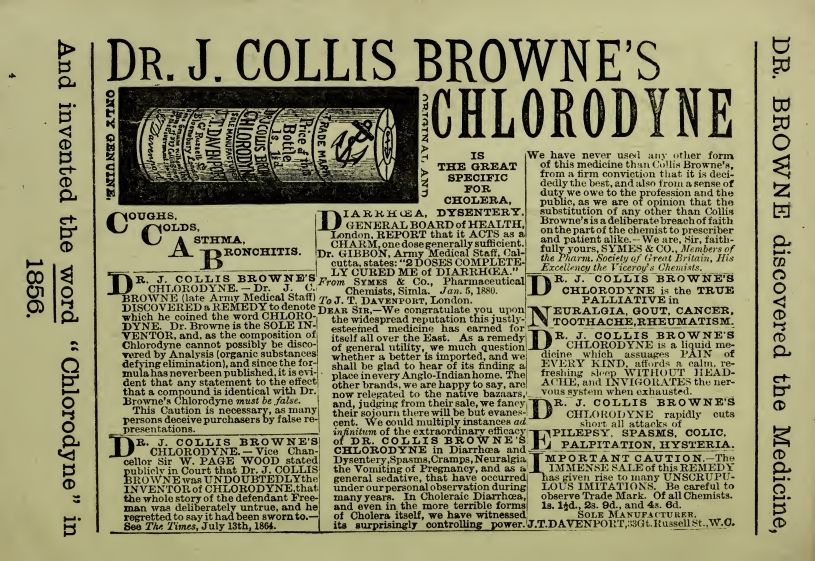

Laudanum was an ingredient of many patent medicines that were

easily available, one such being Dr Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne, a mixture of

laudanum, chloroform and tincture of cannabis, sold as a pain-killer, sedative

and remedy for cholera, dysentery and diarrhoea (amongst other complaints). It

was highly addictive and responsible for many accidental and deliberate deaths.

|

| Freeman's Chlorodyne |

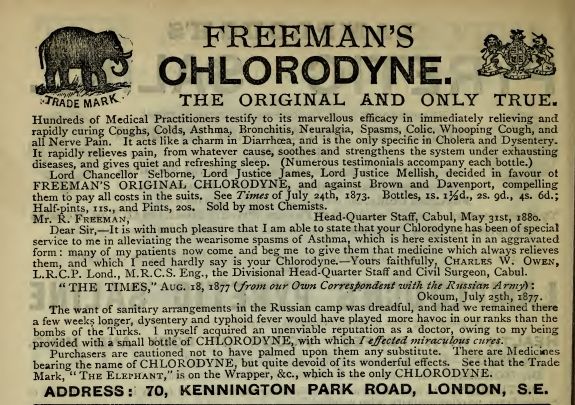

Other manufacturers produced their own chlorodynes, such as Freeman’s,

Teasdale’s and Towle’s, competition was strong and local chemists would also

mix their own, generic versions from recipes in the pharmacopoeias.

Furthermore, as a medicine, there was no excise duty on laudanum, unlike

alcohol, making it an attractive choice for recreational use.

|

| Dr Collis Browne's Chlorodyne |

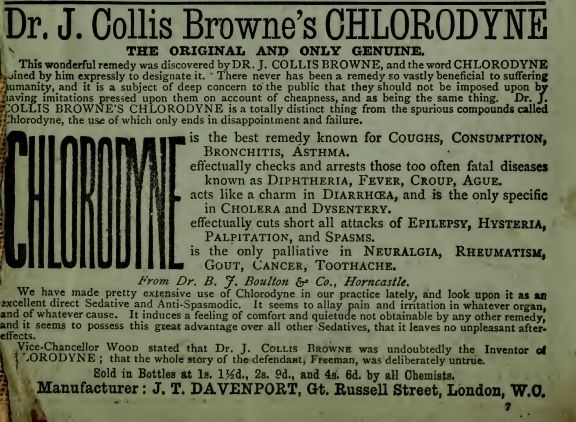

In The Sign of

Four, Sherlock Holmes takes his hypodermic from its neat morocco case,

rolls back his left shirt-cuff, looks ‘thoughtfully upon the sinewy forearm

and wrist all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-marks’ before he

injects a seven per cent solution of cocaine into a vein.

|

| Sherlock Holmes |

So, not a infrequent

user then, and Dr Watson disapproves, he is a doctor after all, but he is not

shocked or surprised, his reaction is more that of your local general

practitioner to one of today’s habitual smokers. It’s art, of a slight sort,

reflecting life.

|

| Charles Dickens - Dictionary of London - 1882 |

And in life itself, you had writers like Charles Dickens whose

Dictionary of London, an early sort of tourist guide, helpfully pointed

out where you might find ‘Johnny the Chinaman’ and his opium den if you

found yourself adrift in the capital, (just off the Radcliffe Highway, down the

narrow alley hard by Quashie’s Music Hall, if you’re interested, although I

suspect it no longer receives clients. Limehouse, in particular, was also

notorious for its opium dens). Punch, naturally, had a take on the

situation.

|

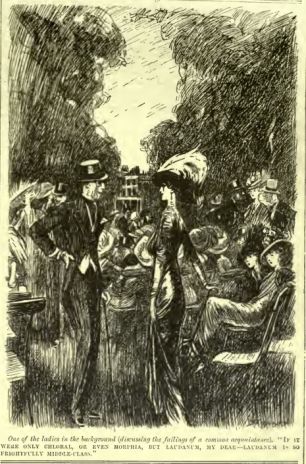

| Punch - July 11 1912 |

A cartoon of 1912 shows a slight young thing conversing with a

monocled man-about-town, whilst in the background, judgemental ton

ladies discuss her habit – they sniff,

“If it were only chloral, or even morphia, but laudanum, my dear, - laudanum is so frightfully middle-class."

The use of intoxicants was so widespread that some modern historians have

called the period between 1870 and 1914 ‘The Great Binge’. When the Great War

broke out, Harrods offered handy boxes containing cocaine, morphine, heroin and

all the assorted paraphernalia, all packed and ready for shipment to our boys on

the frontlines. Drugs were very cheap, easily available, totally unrestricted

and were positively encouraged by the medical men – why suffer when the marvels

of modern science could alleviate your many discomforts?

|

| Thomas Healde - The London Pharmacopoeia - 1796 |

It’s Progress with a

capital P, we’re not living in the Dark Ages any more, we can make all it go

away and life can be free from all unnecessary suffering. Others yet went at

it like a bull at a gate – they saw the squalor, the inequality, the

hopelessness, the cruelty, the whole sorry mess that one tiny section of humanity

was industriously inflicting on the rest of humanity and they sought any

thankful oblivion from the nightmare that was on offer, with an admirable fin

de siècle and millenarianistic zeal.

|

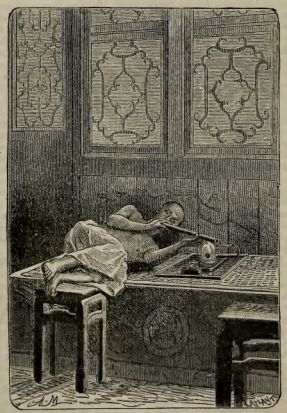

| In an opium den |

The figures are interesting in

themselves; in 1850, opium imports into London amounted to 103,718 lbs, in the

following year they increased to 118, 915 lbs, and in 1852, imports jumped to

250,790 lbs. Opium imports were one thing, but opium exports were quite

another.

No comments:

Post a Comment