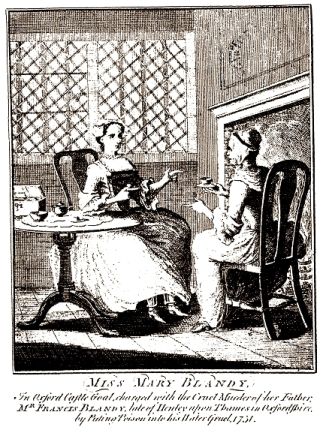

Miss Mary Blandy spent the early days of her

incarceration in something more like a withdrawal from the world than the

normal imprisonment that a suspected murderess might expect in the eighteenth

century. She took her Hyson tea, played a hand of whist, walked in the

Oxfordshire sunshine.

|

| Miss Mary Blandy in Oxford Castle |

But the genteel façade began to be chipped away. News

reached her that her father had died without making a will, unusual for a

lawyer maybe, and she was the sole heiress to his fortune which, to her shock,

amounted to something less than four thousand pounds. The promised dowry of ten

thousand pounds, which had so attracted her Scottish nobleman, was a figment of

the sycophantic attorney’s imagination.

|

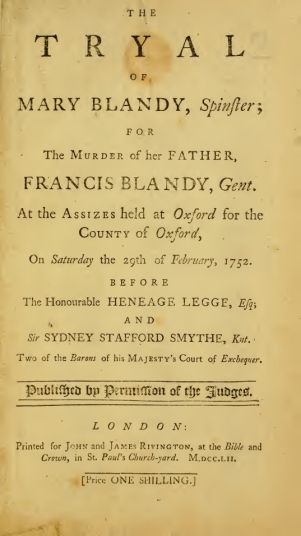

| The Tryal of Mary Blandy - 1752 |

The Secretary of State heard whispers

that there was a plot being prepared to

free the parricide and he sent orders to Oxford that a more careful watch

should be placed on her. The garden walks came to a sudden end and shackles

were riveted around her slender ankles. The tea-drinking and card games were

substituted by chapel services and her only visitor was the prison chaplain.

|

| The Tryal of Mary Blandy - Two Shilling Folio edition |

Rumours and speculations abounded – she had also poisoned her mother, she had

poisoned Mrs Pocock, a family friend, she had spent her fortune bribing

officials, she was still in correspondence with Cranstoun, she was secretly

married to the keeper’s son, witnesses against her were ‘being taken care of’,

she was a drunkard, she was an habitual user of profanities, she never attended

church services, even that she had escaped.

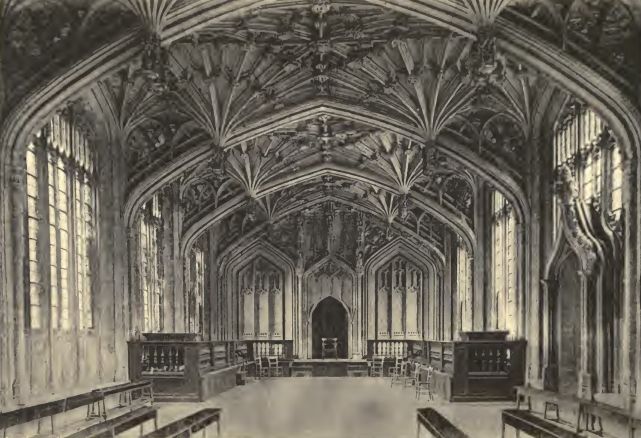

Concerns were aired that the servants, Gunnel

and Emmet, might possibly succumb to the same fate as their former master, and

an early trial was recommended. The town hall at Oxford was undergoing

refurbishment and the University refused the use of Sheldonian Theatre, so the

trial began in the hall of the Divinity School at eight o’clock in the morning

of Tuesday March 3rd 1752.

|

| Hall of the Divinity School, Oxford |

The indictment charged the prisoner with

the wilful murder of Francis Blandy by administering to him white arsenic at

divers times during 1751. The trial was remarkable as it was the first one of

which there is any detailed record, in which convincing scientific proof of

poisoning was given. The Crown case opened with the medical evidence from Drs

Addington and Lewis, and Norton the apothecary, who presented proof that the

arsenic was the cause of death, arsenic was in the gruel pot, and arsenic was

in the packet that the witness had attempted to burn.

The servants were called

and gave evidence that they had heard Miss Blandy wish her father dead and that

she had referred to him in less than daughterly terms. Her hurried,

intercepted, note to Cranstoun was produced and read, witnesses from the Angel

tavern were called and the Crown closed its case.

|

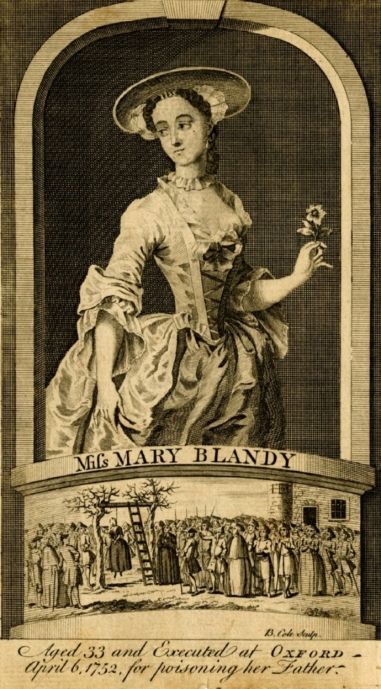

| Miss Mary Blandy |

Then Mary Blandy took the

stand but gave little evidence other than stating that she thought the powder

‘an inoffensive thing’ that she had given to her father to procure his love.

The defence called its own witnesses, former servants who said that they had

never heard Miss Blandy speak a word against her father. Edward Herne, the

inattentive sentry and old flame, told how he had visited the house at least

four times a week and had always found Mary to be a exemplary, attentive

daughter.

After thirteen hours in the courtroom, the jury consulted for five

minutes without even withdrawing, and immediately returned a guilty verdict. Mr Baron Legge

pronounced the death sentence on Miss Mary Blandy, who was then returned to

Oxford Castle, stepping “… into the Coach with as little Concern as if she

had been going to a Ball.”

|

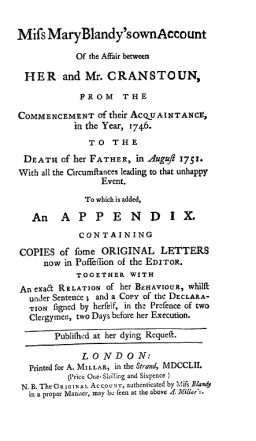

| Miss Mary Blandy's Own Account - 1752 |

A flurry of pamphlets appeared, stating the

truth of both sides, and Mary produced her own ‘True Account’ of what

had happened. None of it made any difference. The date of the execution was

fixed for Saturday April 6th but the University authorities objected

that it was an unseemly thing for Holy Week, so the date was moved to the

following Monday.

|

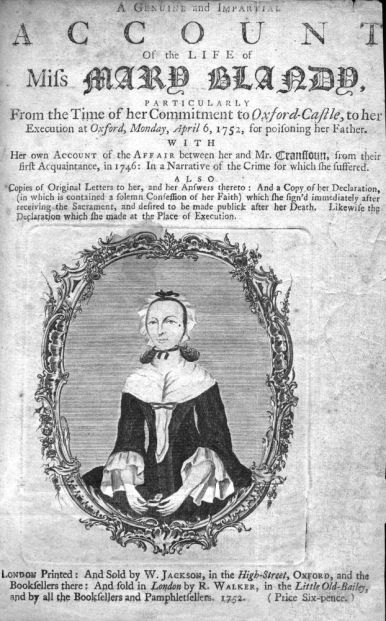

| Account of the Life of Miss Mary Blandy |

At nine in the morning, Mary Blandy was led from her cell

and, dressed in black crepe and with her arms tied with black paduasoy ribbons,

carrying a prayerbook and two guineas for the hangman, she walked to the Castle

Green. Before a silent, respectful crowd of over five thousand, she made a

modest speech admitting her guilt and denying any involvement in any other

deaths. She began to climb the ladder but stopped when five steps up and asked ‘for

modesty’s sake’ not to be hanged high. She went up two more steps and

stopped again, fearing that she might fall, a handkerchief was placed over her

face and, with the prayerbook still in her hand, she was turned off the ladder.

|

| The Execution of Miss Blandy |

After half an hour, she was taken down but no hearse or coffin had been

brought, so the body was thrown over the shoulder of one of the sheriff’s men

and carried away, immodestly exposing her legs to the gaze of the onlookers.

She was laid in the sheriff’s house during the afternoon and then taken to

Henley, where at one o’clock in the morning she was buried in the same grave as

her mother and father in the chancel of Henley Parish Church.

|

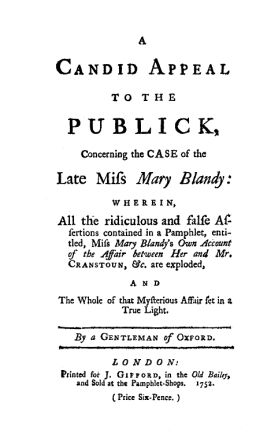

| A Candid Appeal to the Publick - 1752 |

Her genteel

departure came just in time, as a new law was passed later in the same year whereby

those condemned for murder where to be hanged the next day but one after

sentence was passed and then their body passed on to the surgeons for

dissection or, at the judge’s discretion, hanged in chains. The case of Mary

Blandy was followed greatly at the time although she almost forgotten now.

|

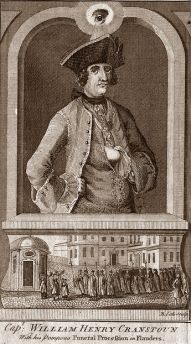

| Capt. William Henry Cranston |

And

what, you may ask, became of the Honourable William Henry Cranstoun? Well, when

news of the arrest of his intended reached his ears, this officer and gentleman

fled to Scotland and when a writ for his arrest was issued, he ran for the

continent as quickly as his scrawny little legs could carry him. He sought

refuge with a kinswoman in France and assumed her maiden name, Dunbar, but his

arrival became known to officers in the French service who were related to his

wife and when they vowed revenge for his shabby treatment of her, he scampered

off to Furnes, a town in Flanders owned by the Queen of Hungary.

There, in late

November 1752, he fell ill with a mystery illness and on December 2nd

he died, in great agonies, you may be pleased to hear. His goods, including his

embroidered waistcoats, were sold off to pay his debts. On his deathbed, he

converted to the Roman Catholic Church, and the death of so prominent a convert

impelled the local clergy to arrange a magnificent ceremonial funeral in the

Cathedral, with a procession and high requiem mass, all attended by monks,

friars and the magistrates of the town. We can only assume that they were

unaware of the true identity of their latest celebrity.

|

| Commodore Howe - or is it? Compare with the above portrait of Cranstoun. |

In an interesting

aside, in 1760, John Fuller published a three volume edition of The Naval

Chronicle; or, Voyages, Travels, Expeditions. Volume Three included

accounts of various prominent naval officers, illustrated with woodcuts of

these eminent gentlemen, but when it came to Commodore Lord Richard Howe, who later

became First Lord of the Admiralty, Fuller must not have had a portrait of Howe

available, as he had a portrait of Cranstoun reworked and presented in his book

as the image of the naval hero.

Quite what ‘Black Dick’ Howe thought of

his portrait when he was confronted with Fuller’s presentation of the odious

Cranstoun as his own likeness has not made its way down to us. I do not expect that it was

one of enthusiastic approval.

No comments:

Post a Comment