The task of separating fact from fiction is, for me

at least, one of the most fascinating elements of studying history. The most

valuable evidence comes from what are called ‘primary sources’, which are

artefacts that are contemporaneous with whatever it is that historians are

considering. These can be written sources – reports, diaries, letters and so on

– but can also be almost any other things that you may care to imagine, even

down to the minutiae of everyday life.

Other things that come from later times,

things like autobiographies, reconstructions and so on, are called ‘secondary

sources’ and are necessarily, consciously or unconsciously, coloured by their

creator’s own conceptual filters. That isn’t to say that primary sources are

always entirely free from bias, and that is where the separation of fact and

fiction enters into the equation.

|

| Richard III |

Let’s look at the death of Richard III, as an

example. Richard died at the Battle of Bosworth Field, which happened on August

22nd 1485, and there can be no credible doubt about that. The

chroniclers who wrote about the battle agree that he died in the thick of the

battle, from wounds inflicted during the fighting. The continuer of the Croyland

Chronicle, which is the nearest thing to a contemporary account, has little

to say about the actual battle,

“For while fighting, and not in the act of flight, the said king Richard was pierced with numerous deadly wounds, and fell in the field like a brave and most valiant prince.”

|

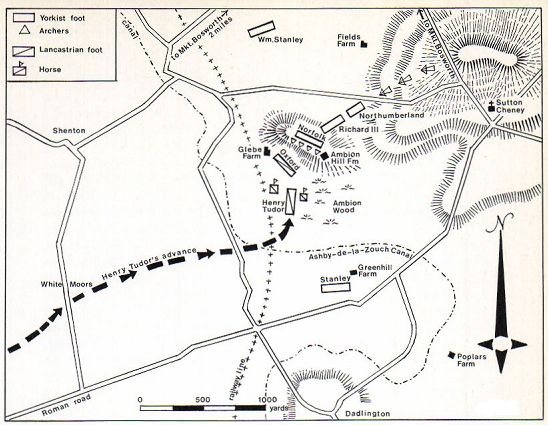

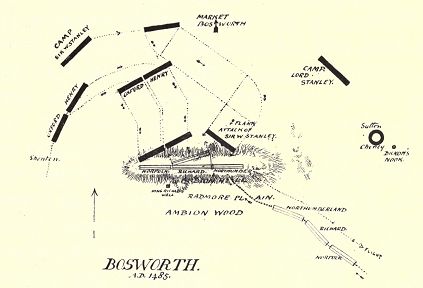

| Plan of Battle of Bosworth Field |

Another chronicler,

Philip de Commines, a French diplomat writing a little after the events, is

even briefer,

“… The Earl of Richmond, the present king ... in a set battle defeated and slew this bloody King Richard,”

and Robert Fabyan, in the New

Chronicle of England is briefer yet,

“…nere vnto a village in Leycestershyre, named Bosworth … kynge Richarde was there slayne.”

Polydore

Vergil, again writing slightly later, yet still in living memory of the battle,

has,

“King Richerd alone was killyd fyghting manfully in the thickkest presse of his enemyes.”

|

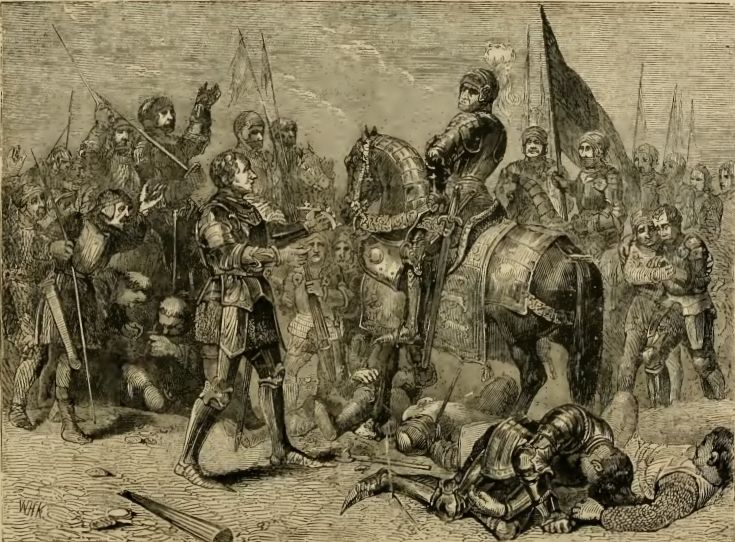

| Henry VII offered the crown on Bosworth Field |

Now it has to be said that Henry VII, victor at

Bosworth, had later writers skew events to suit the Tudor interpretation and

was keen to present Richard in a very bad light but on the other hand, it was

better for his image if he gained the crown by taking it from a formidable

opponent – it reads better if his foe was someone worth besting, rather than

snatching kingship from a snivelling coward caught hiding in a hole in the

ground. However, what is recorded next doesn’t really show Henry as a gracious winner,

as the chroniclers tell what happened to Richard’s corpse. Croyland

says,

“… the body of the said king Richard being found among the dead … many other insults were also heaped upon it, and, not exactly in accordance with the laws of humanity, a halter being thrown round the neck, it was carried to Leicester.”

|

| The view toward Market Bosworth |

Fabyan’s account agrees with the despoliation of Richard’s

body,

“Thanne was the corps of Richarde, late kynge, spoyled, &, naked, as he was borne, cast behynde a man, and so caryed unreuerently overthwarte the horse backe vnto the fryers at Leyceter; where after a season that he had lyen, that all men might beholde hym, he was there with lytel reuerence buryed.”

Vergil too has a

similar version of the fate of the former king,

“In the meane time the body of king Rycherd nakyd of all clothing, and layd uponn an horse bake with the armes and legges hanginge downe on both sydes, was browght to thabbay of monks Franciscanes at Leycester, a myserable spectacle in good sooth, but not unworthy for the mans lyfe, and ther was buryed two days after without any pompe or solemne funerall.”

|

| View over Bosworth Field |

The Chronicle of the Grey Friars (that

is, the same Franciscans mentioned above), is maddeningly brief,

“This yere in August the erle of Richmond with the erle of Pembroke that long hade bene banyshed, came into Ynglond, and the other gentylmen that flede into France, [and] made a felde besyde Leyceter, and the kynge there slayne.”

So, it seems

likely, Richard III’s body was stripped, a halter put about his neck, and his

body thrown over a horse’s back and taken to Leicester where, after it had been

displayed publicly, the Franciscans buried it in their church of St Mary’s.

Henry VII raised a marble monument but this was lost during the dissolution of

the monasteries made under his son, Henry VIII.

|

| Epitaph to Richard III - from George Buck - The History of the Life and Reigne of Richard III - 1647 |

A prominent local citizen,

Robert Heyrick, acquired the land on which the monastery had stood and he had a

small column built on the site, with a dedication to ‘King Richard III, some

time king of England’, which was described by Sir Christopher Wren in 1612,

but this too has since been destroyed, and by the days of Charles I, the site

of the grave had been lost. A local tradition had it that the bones of Richard

had been taken from the grave and thrown into the River Soar.

|

| Plan of the Battle of Bosworth |

The stone coffin

in which the body had lain was supposed to have been taken to a local inn, the

White Horse Inn, and was used as a water trough, but when the historian William

Hutton went in search of it, in 1758, locals told him that it had been broken

up and used to build steps in the cellar of the same inn.

|

| The White Boar, later the Blue Boar, Leicester |

Another inn, named

for Richard’s heraldic device, was the White Boar, where Richard was

said to have spent his last night, but this was renamed the Blue Boar

when the Tudors came to power and was eventually demolished in 1836.

|

| The Badge of Richard III |

And then,

in 2009, Philippa Langley, Secretary of the Scottish Richard III society

launched a project to attempt to discover the remains of the only English king

whose resting place was unknown. In collaboration with the University of Leicester

Archaeological Services, surveys were made and in 2012, test trenches were

excavated in the staff car park of Leicester Social Services, where it was

thought the former monastery of St Mary’s had once stood. The ULAS website

tells the whole story and a remarkable story it is too, I strongly recommend

you visit it at least once, but suffice to say that a skeleton was found that

that, when a battery of various tests had been completed, was declared to be ‘beyond

reasonable doubt’ that of the lost monarch.

|

| Henry VII crowned at Bosworth |

The skull showed evidence of

damage that could only have been inflicted during mortal combat, confirming the

chroniclers’ reports that Richard had died in battle (and negating the legend

that his body had been dumped in the Soar). You simply don’t get better primary

evidence than that! As I write this, it is still undecided where the bones will

eventually re-interred.

No comments:

Post a Comment