Their story will always be remembered as one of

history’s most heartbreakingly romantic tragedies. It has all the elements that

you could ever wish for – two orphaned young brothers locked away in the deep,

dank dungeons of the Tower of London, one of whom is the King of England until

his crown is usurped by their wicked uncle who then arranges, one dark

midnight, to have the young innocents murdered in their beds and their bodies

hidden away in the depths of the Tower. The tale has been embroidered over the

centuries, with threads added and details embellished, preludes and aftermaths

interwoven, and loose ends neatly tied. So much so, that the facts will never

be known.

|

| The Murdered Princes in the Tower |

We do not have much in terms of what we can even consider to be

primary sources –an Italian, Dominic Mancini, was in London in 1483, and later

in the year, when he had returned to France, he made a report of his visit in

which he repeated a rumour that Richard was suspected of killing his nephews.

It is possible that this is the report influenced Guilliame de Rochefort, Lord

Chancellor of France, who repeated the rumour at the Estates-General in

Tours in 1484, at which another French diplomat was present.

In the Memoirs

of Philip de Commines, this diplomat (who did not come to England but was

in contact with many on both the Lancastrian and Yorkist sides in northern France) whose memoirs

were not written until about seven years later and not published until 1524,

wrote,

“Not long after, he [King Louis XI of France] received letters from the Duke of Gloucester, who had made himself king, styled himself Richard III, and barbarously murdered his two nephews.”

|

| Richard III by John Rous |

An unreliable source is John Rous’s Historia

Regum Angliae, in which we find,

“The throne of the murdered King was then usurped by their Protector, Richard the tyrant, who had remained two years in his mother's womb, and at Fotheringay on the feast of 4,000 virgins was born with long hair, and his teeth complete … such was Richard, who received his master Edward with kisses and fawning caresses, and in three months murdered him and his brother, poisoned his own wife, and what was most detestable both to God and the English nation, slew the sanctified Henry VI.”

I do hope that

you will agree with me that anyone who believes in two-year pregnancies is not

really to be trusted when it comes to other matters.

|

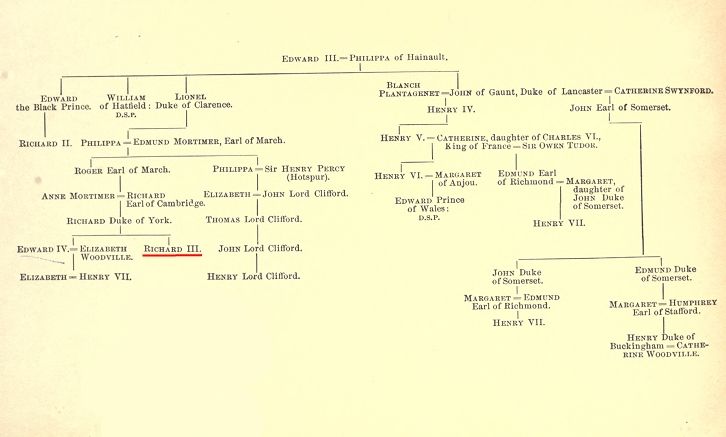

| An abridged royal family tree |

The Grey Friars’ Chronicle

has a single, cryptic line,

“And the two sonnyes of kynge Edward were put to cilence, and the duke of Glocester toke upone hym the crowne in July, wych was the furst yere of hys rayne.”

That ‘put to silence’ might mean that

the princes were ‘silenced’ by being killed, but it might just be that

they were ‘silenced’ by being removed to a place where they could not be

heard, a place like the Tower of London, and the deliberate ambiguity is a

proleptic safeguard, written by a nervous chronicler who feared how an as-yet unresolved future

might turn his record against him.

The Continuation of the History of

Croyland has the following entry,

“In the meantime, and while these things were going on, the two sons of king Edward before-named remained in the Tower of London … while a rumour was spread that the sons of king Edward before-named had died a violent death, but it was uncertain how.”

|

| The Bloody Tower |

Robert

Fabyan’s New Chronicle of England and France for the year 1483 has,

“IN this yere the foresayd grudge encreasinge, and the more for asmoche as the common fame went that kynge Richarde hadde within the Tower put vnto secrete deth the ii sonnes of his broder Edwarde the iiii.”

Fabyan’s Chronicle

may have been ‘revised’ to suit his new Tudor patrons; it was not printed until

1515. When the next accounts appear, time and circumstance had given enough

space for twists to be added to the story.

Polydore Vergil wrote his History

of the Life of Richard III over twenty years after the events, and at the

behest of Henry VII, who had defeated Richard in battle and had assumed the

throne in his stead. Vergil wrote that Richard,

“ … determynyd by death to dispatche his nephewys, because so long as they lyvyd he could never be out of hazard; wherefore he sent warrant to Robert Brakenbury, lyvetenant of the towr of London, to procure ther death with all diligence, by some meane convenyent.”

|

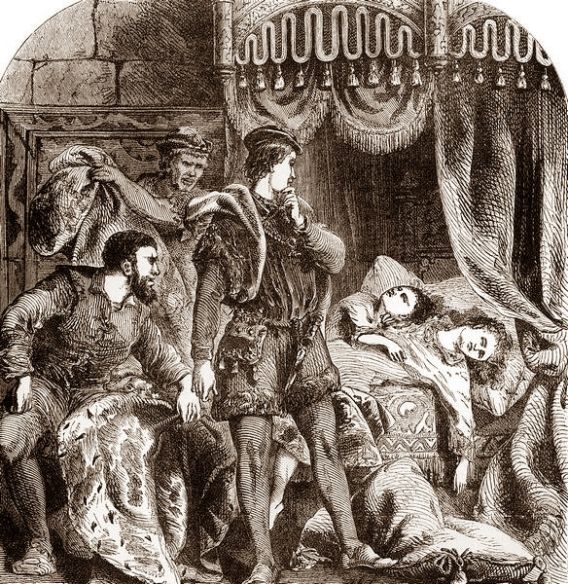

| The Princes in the Tower |

Brakenbury was reluctant to carry out the murder, so Richard arranged for James

Tyrrell to do the deed and he,

“… rode sorowfully to the Towere London, and to the woorst example that hath been almost ever hard of, murderyd those babes of thyssew [the issue] royall …. king Richard, delyveryd by this fact from his care and feare, kept the slaughter not long secret, who, within few days after, permyttyd the rumor of ther death to go abrode, to thinterit (as we may well beleve) that after the people understoode no yssue male of king Edward to be now left alyve, they might with better mynde and good will beare and sustayne his governement.”

And this is the version of events that became

the standard account of the murder of the Little Princes in the Tower. Sir

Thomas More, writing for Henry VIII, another Tudor royal patron, and who was

three years old when the event occurred, takes the story of Brakenbury’s

reluctance, adds some hired bully boys who,

“... about midnight (the sely children lying in their beddes) came into the chamber, and sodainly lapped them vp among the clothes, so bewrapped them and entangled them, keping down by force the fetherbed and pillowes hard vnto their mouthes, that within a while smored and stifled, theyr breath failing, thei gaue vp to God their innocent soules into the joyes of heauen, leauing to the tormentors their bodyes dead in the bed.”

Add to this Shakespeare’s version in his Richard III and

Richard’s reputation as a murderous traitor is sealed.

|

| J E Millais - The Princes in the Tower - 1878 |

The legend received

another shot in the arm during the Victorian times when mawkishly

sentimentalised history paintings came into vogue, and the two boys, hopelessly

vulnerable but heroically brave, cruelly abandoned but pluckily proud, were

ideal subjects for this niche market. Consider their pale little faces

surrounded by shocks of blond curls shining like saints, as they shiver,

hand-in-tiny-hand in their gloomy gaol, uncomprehendingly awaiting whatever

their terrible fate has next in store for them.

|

| Clements Markham - Richard III : His Life and Character - 1906 |

There have been attempts to

rescue Richard’s name, beginning most notably with Horace Walpole’s Historic

Doubts on the Life and Reign of Richard III (1768), and followed over the

years by others, including Richard III: His Life & Character Reviewed In

The Light Of Recent Research, by Sir Clements Markham in 1906, and a

Richard III Society was founded in 1924, with the aim of reappraising the

King’s posthumous reputation. But that's for another day.

No comments:

Post a Comment