On the evening of January 27th 1905, Mr

Frederick Wells, a mine manager, was making his rounds of the new No 2 Premier

Mine, near Pretoria, South Africa, when he saw something gleaming the rays of

the dying sun, at the brink of the open workings. He picked up a large stone,

put it into the pocket of his sack coat, and went back to the company office to

examine his find. At first, it was thought that Wells had picked up a piece of

rock crystal and it was almost thrown aside, but on closer examination, the stone

was found to be a diamond of unprecedented size, weighing over 1.3 pounds, or

3253 ¾ carats.

|

| The Last Open Workings at Kimberley - 1889 |

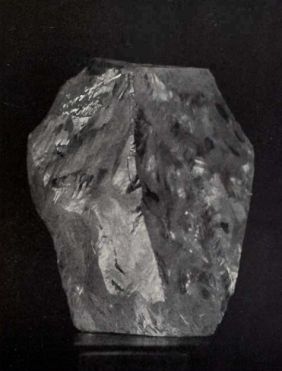

As the stone had a distinct fracture line on one face, it was

thought to be a fragment of a larger octahedral crystal, although the

corresponding piece has not (yet) been unearthed. The stone was named after the

chairman of the Premier (Transvaal) Mining Company, (later Sir) Thomas

Cullinan, and purchased by the Transvaal Government for £200,000, although it

was insured for £1,500,000. It was decided that this huge gemstone should be

presented to King Edward VII as a gift for his 66th birthday, as a

suitable token of the entry of South Africa into the British Empire, but there

was the problem of transporting it from the Cape to England.

|

| The Cullinan Diamond in its rough state |

A facsimile stone

was sent by steamboat, and accompanied by detectives, as a diversionary tactic

to attract potential thieves, whilst the real stone was packed into a plain box

and sent by normal parcel post (although it was sent by registered mail). To

the dismay of London jewellers, when the rough diamond was examined, the Crown

authorities decided to ship the stone to Amsterdam for cutting and polishing.

|

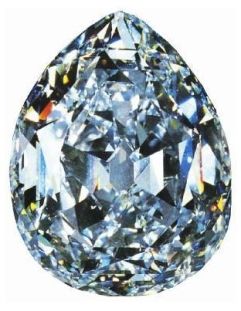

| Cullinan I in its cut state |

The stone was not perfect, and it would have been impossible to form it into

one enormous brilliant cut gem; there was a small, black spot in the centre,

and although the stone was remarkably clear, there were other graphitic spots

close to the surface, and other discolouration on the outside. At one point,

there was an internal crack, and at another, there was an opaque, milky mass,

of a brown colour, with what looked like iron oxide stains.

|

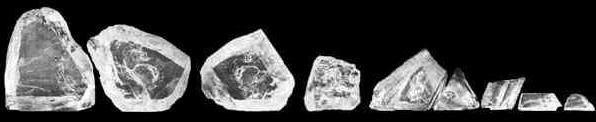

| The Fragments of the Cullinan after cleaving |

Therefore, the

decision was made to break up the rough stone into smaller parts, with the work

to be carried out by the house of J Asscher and Co, of Amsterdam and Paris. At

the beginning of 1908, the Cullinan Diamond was moved, under escort, to the

Asscher fabriek on Tulp Straat, where it was kept in a vault with

concrete and steel walls two feet thick, with Dutch secret servicemen and

Scotland Yard detectives guarding the establishment.

|

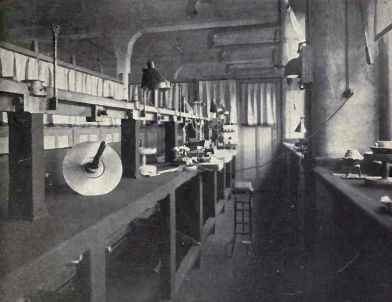

| The Cutting Room at Asscher's where the Cullinan was cut |

The experts examined the

stone for weeks, deciding how best to cut it before, on February 10th

1908, Mr Joseph Asscher, the finest diamond cleaver in the world, made ready to

make the first cut, under the supervision of Messrs M J Levy and Nephews, the

precious stone experts. Models had been made in crystal, to give Asscher a

guide to the desired effect, and a cut, three quarters of an inch deep was made

with a diamond saw along the line of cleavage. A special steel, comb-shaped

knife, without a handle, was made and inserted into the cut on the stone and

with a steel bar, Asscher struck the back of the knife. The steel knife broke

and the stone remained intact.

|

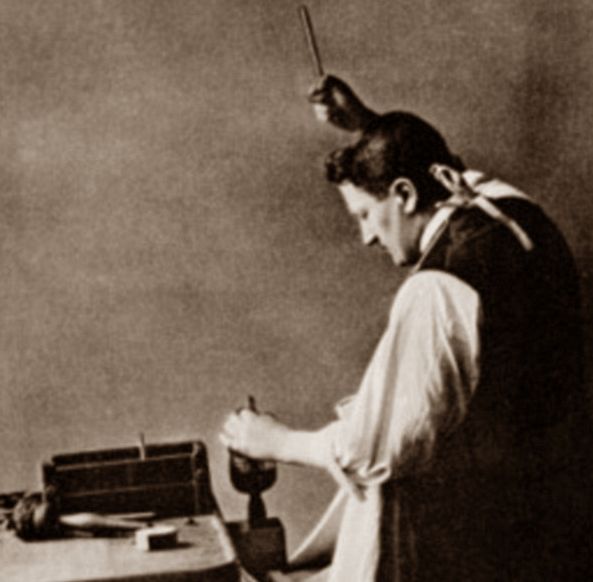

| Joseph Asscher prepares to cleave the Cullinan Diamond |

A replacement knife was placed in the cut and

Asscher struck again – this time the Cullinan diamond split into two parts,

exactly as planned. (There is a story that Asscher insisted on having a doctor

and nurse present, and when the stone broke, he fainted on the spot. This is

almost certainly apocryphal).

|

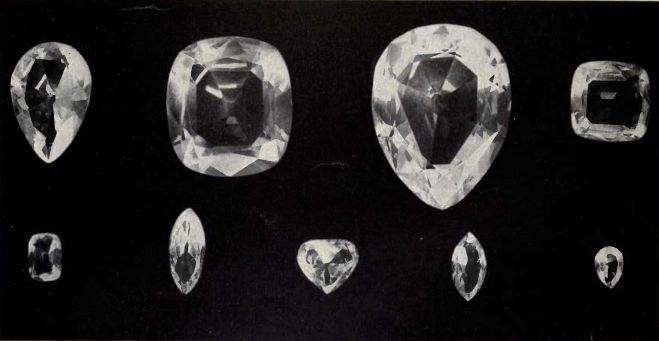

| The Nine larger Cullinan cut stones |

Later in February, the larger portion was again divided,

and over the months until November, the rough diamond was divided again and cut

and polished to produce nine large gemstones, 96 smaller stones and nine carats

of uncut bort. Cullinan I was, then, by far the largest cut diamond in the

world, at 516 ½ carats, (the previous largest brilliant, the Jubilee, weighs

239 carats, and the Koh-i-noor pales into an insignificant 102 ¾ carats), with

Cullinan II weighing 309 3/18 carats.

|

| Queen Elizabeth II - Cullinan I is in the head of the Sceptre |

The pear-shaped, brilliant Cullinan I was

placed in the Sovereign’s Sceptre, and the brilliant-cushion Cullinan II was

put into the Imperial State Crown, below the Black Prince’s ruby. The other,

smaller Cullinan diamonds were mounted in other pieces of royal regalia, and it

is interesting to note that the four largest pieces amount to 986 carats of cut

and polished jewels, taken from a rough diamond of over 3,000 carats.

|

| The Imperial State Crown - with Cullinan II in the front |

Above a

certain size, there is almost no commercial market for large gemstones, for

there are few people wealthy enough to buy them, and fewer still prepared to wear

something that looks like it might have been purloined from a crystal

chandelier, and they can only be displayed in the context of royal regalia worn

on state occasions, supplemented with hundreds, or thousands, of smaller gems.

Cullinan I and II are, effectively, beyond price, as there is nothing close to

matching them and certainly nothing to replace them, and they are set in the

Crown Jewels, which are, again, simply priceless, but just for the sake of

argument, the bidding for either stone would not open at a penny less than

£200,000,000.

|

| Cullinan II |

Not bad for something that almost got thrown out of a

mine-manager’s estate-office window.

No comments:

Post a Comment