I will tell you about Lt Col A D Wintle MC on

another occasion, but just for now I want to mention how, in his remarkable

autobiography, The Last Englishman, he recalls how, as a ten year old,

he was entered for Le Certificat d’Etudes Primaires (although English,

he received his primary education in France), and that he achieved an

unprecedented score of 99%, an astonishing feat for an English boy, of all

things, to accomplish. Flushed with pride, young Alfred Wintle told his father of his

remarkable triumph, only to be brought firmly back to earth when Father barked,

“I expect you were playing the fool or you would have got one hundred per cent.”

|

| J J Audubon - by his son J W Audubon |

Which, if it proves anything, just goes to show that, no matter what

you do, in someone else’s eyes, you’ll never quite manage to cut the mustard.

So, let it be with Audubon. On the afternoon of February 24th 1827,

he read an original paper, entitled ‘Notes on the Rattlesnake’* to the

Wernerian Society of Natural History of Edinburgh.

|

| J J Audubon - Notes on the Rattlesnake - Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal - 1827 |

There was a wide-spread

belief at the time that certain creatures, in particular venomous snakes, had

an almost supernatural power of ‘fascination’ that allowed them

mesmerise their prey, rendering it immobile. Audubon sought to disprove this

idea of the ‘theoretical naturalists’ by empirical proof gained from

observation of snakes in the field. His contention was that the real power of

snakes lay in their speed, their abilities to expand and contract their bodies,

sharp-sightedness, in being amphibious, and their torpidity in winter and prolonged

abstinence during other periods whilst retaining their venomous facility.

|

| Grey Squirrel - from Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America |

He

told the Society how he had observed rattlesnakes hunting grey squirrels,

chasing them with remarkable speed in the branches of trees and upon open

ground, and how he has watched a rattlesnake kill a squirrel and swallow it

whole, tail first, how he had killed that snake and opened its body, to find

the squirrel

“… lying perfectly smooth, even as to its hair, from its nose to the tip of its tail.”

Likewise, he related how he had seen, at first

hand, a snake emerge from a river and begin to sun itself on a rock. Noticing a

bulge in its middle, he shot the snake, opened its belly and found a catfish so

fresh that, when dressed, he ate it for his own supper. Similarly, he had watched

snakes hunting bull-frogs, chasing them underwater and bring them out of the

water in their mouths, to devour them on land.

|

| The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal - 1827 |

Once, when out duck-hunting, his

son had discovered a large rattlesnake lying torpid beneath a log, which they

placed in a cloth bag and took to their camp. When the bag had been placed

close to the campfire, the warmth roused the snake, which became very active

and rose in defence, threatening as if to strike. When removed from the heat

source, this snake had again become torpid, and he told how they had taken it

home, and had watched it become active or torpid depending on its proximity to

warmth.

|

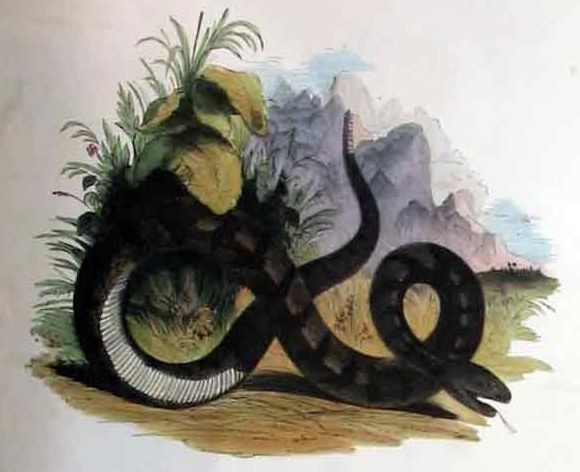

| Rattlesnake |

Another captive snake had refused to feed for three years, and had not

grown the least fraction of an inch during that time. He concluded his talk by

describing a nest of rattlesnakes, comprising over thirty individuals, seen

during the mating season, all of them ‘glistening with cleanliness’ and

hissing, threatening to strike at anyone or anything that approached them.

Audubon finished the meeting, handed his manuscript to Professor Jameson, and

left to the cheers and applause of the Society.

|

| Journal of the Franklin Institute - 1828 |

A few months later, Professor

Jameson published Audubon’s paper in The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal,

and in due time the article was reprinted in the Journal of the Franklin

Institute of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the next edition, Dr Thomas P

Jones, editor of the Journal, wrote an editorial piece condemning

Audubon’s article as ‘a tissue of falsehoods’ that had been included in

haste, without proper scrutiny, and that Jones had since received a

communication from a ‘scientific friend’ that he usefully printed.

“It is a tissue of the grossest falsehoods ever attempted to be palmed upon the credulity of mankind, and it is a pity that anything like countenance should be given to it, by republishing it in a respectable journal. The romances of Audibon [sic] rival those of Munchausen, Mandeville, or even Mendez de Pinto, in the total want of truth, however short they may fall of them in the amusement they afford.”

|

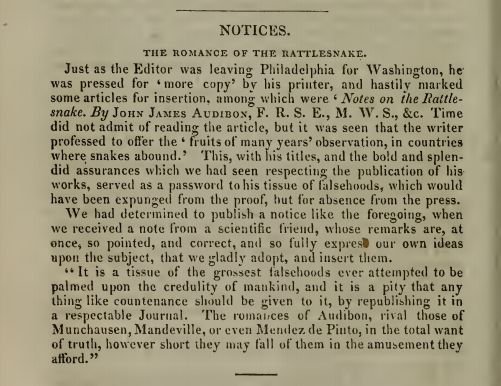

| The Romance of the Rattlesnake - from Journal of the Franklin Institute - 1828 |

Audubon, who was still in England at the time, was

informed of these attacks on his scientific credibility by his friend, Thomas

Sully, and in a reply to Sully, Audubon wrote,

“I feel assured that the pen that traced them must have been dipped in venom more noxious than that which flows from the jaws of the rattlesnake!”

|

| J J Audubon - Mockingbirds attacked by a Rattlesnake - from The Birds of America |

At the same time as all this was

unfolding, Audubon also published his plate of Mockingbirds defending their

nest from the depredations of a Rattlesnake, which added fuel to the fires of

his detractors. Everyone knows that rattlesnakes did not and could not climb

trees, they scoffed, so what was this hick from the sticks thinking of?

|

| Detail of the above |

Defenders

of Audubon wrote letters in his defence, citing personal experiences of

observing rattlesnakes in trees, bushes, shrubs and atop fences. Ironically, as

Audubon returned to America, the attacks crossed the Atlantic in the opposite

direction, his most vociferous critic being the English naturalist, Charles

Waterton, who lashed out at the Birds of America and the Ornithological

Biographies in the Magazine of Natural History in a series of

letters that began in 1833.

|

| J J Audubon - Notes on the Rattlesnake - in Journal of the Franklin Institute - 1828 |

Tomorrow – What was going on with these attacks on

Audubon?

* - Remember, the British warship that attacked the Polly, the vessel on which Audubon was returning to America was called The Rattlesnake. Was this an omen? Or just a coincidence?

No comments:

Post a Comment