The great French writer, philosopher and gourmand

Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle and the Abbé Jean Terrasson were close friends

but they differed on one account; Fontenelle insisted that his asparagus be

served with an oil dressing whereas Terrasson preferred his served with butter.

One day, the Abbé called on his friend, who had just received a large basket of

his favourite vegetable and, in deference to his guest’s tastes, Fontenelle

instructed his cook to divide the basket into two halves and prepare one half

with oil and the other with butter.

|

| Bernard de Fontenelle |

The friends sat down to chat until it was

time for supper and, after about half an hour, as the Abbé was passing a

pleasantry, he fell into a fit and died. With admirable presence of mind, and

before calling for a physician, Fontenelle dashed to his kitchen door and

shouted to his cook,

“Tout à l’huile, maintenant; tout à l’huile”“All with oil, now; all with oil.”

|

| Asparagus Bundle |

Now, that said, I must say that I am in concert

with the good Abbé on this matter. I prefer my asparagus with butter, (a good,

farmhouse whey-cream butter, if possible), and with a pinch of sea salt flakes and no

more. There are those, like Fontenelle, who advocate a virgin olive oil, and

good luck to them, and some will opt for a hollandaise sauce, mayonnaise and/or

a sprinkling of Parmesan, but I am not amongst them.

|

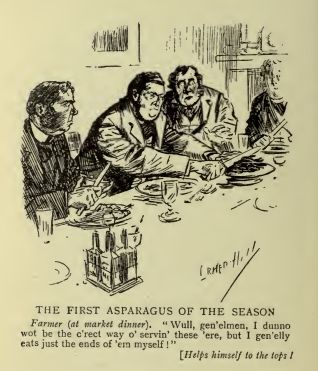

| Wull, gen'elmen, I dunno wot be the c'rect way o' servin' these 'ere, but I gen'elly eats just the ends of 'em myself! |

Asparagus is one of those

things that divides opinion and everyone believes that that their own method is

the only correct way. Hold each stalk separately between your thumbs and

forefingers, and gently flex it. It will snap at just the right place, dividing

the fleshy tip from the woody stem. Then steam the tips over boiling, salted

water for seven minutes, serve on a warm plate with butter and salt. Eat them

with your fingers. And that’s it. Life is already complicated enough.

|

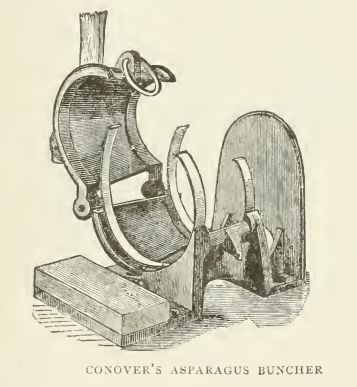

| Conover's Asparagus Buncher |

There are

some who say bind the stalks into bundles and place in boiling water, with the

tips above the level of the water. There are some who use strange devices, made

from silver or ceramic, to hold the stalks as they cook. Some will tell you to

serve the cooked stalks on a clean linen napkin, so as to soak up any surplus

moisture. Other will say that the stalks should be served on cold, dry toast,

also to soak up moisture – and you should no more eat the toast than you would

eat the napkin.

|

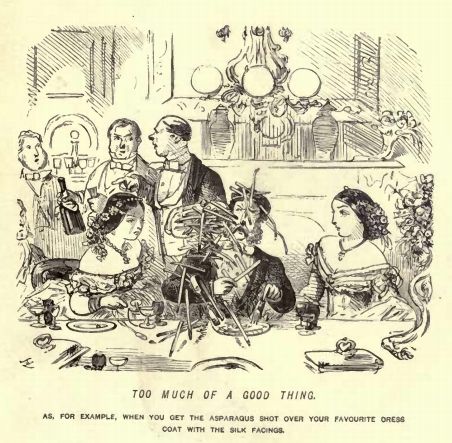

| Too Much of a Good Thing |

The woodier parts of the stalks can be used to make a soup,

with chicken stock, fresh herbs and single cream. Never, ever, under any

circumstances, eat tinned asparagus. You would never wear a pre-tied bow tie

(Would you? I hope not), so why would you even consider eating asparagus from a

tin? You may, on occasion, and only in the company of close friends or blood

relatives, serve boiled asparagus tips with fresh petit pois, straight

from the pod and cooked with the tips, with two or three fresh mint leaves

added to the pan.

|

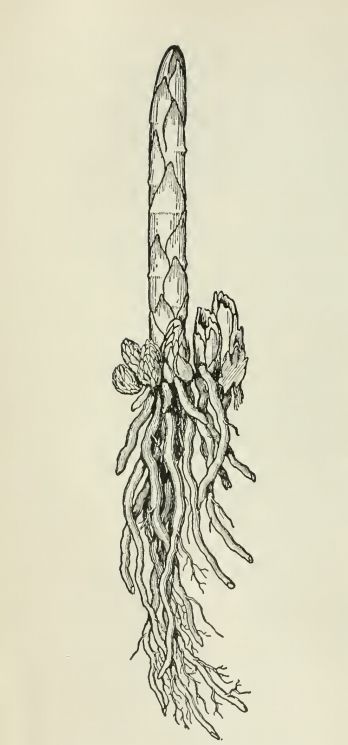

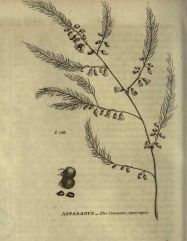

| Asparagus |

Just as cooking and serving preferences differ, so do

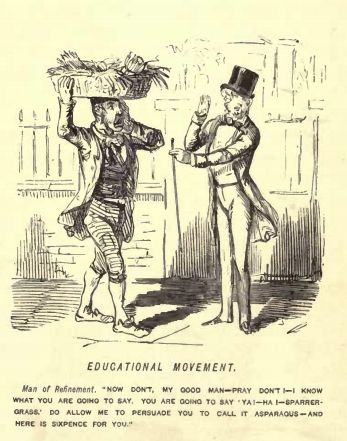

etymological thoughts. One school says that the word ‘asparagus’ derives

from the Turkish koosh konmaz (what the sparrow [small bird] alights not

on), with links to ‘asfoor – Arabic for ‘bird’. There are others

who prefer the Greek, ‘a’ – meaning ‘not’ and ‘sparagos’ –

‘to tear into pieces’ άσφάραγος – referring to a thorny plant that

resists being handled.

Those favouring the Latin cite sparagus and sparagi,

and in early English texts it occurs as sperage, but over the years a

false folk etymology grew up that the name derives from ‘sparrow-grass’.

Certainly, in popular usage, sparrow-grass came to be the most widely used

term, so much so that Walker, in his Pronouncing Dictionary (1791)

states,

“Sparrow-grass is so general that asparagus has an air of stiffness and pedantry.”

Samuel Pepys, in his Diary, (April 20th

1667) writes that he

‘… brought home with me from Fenchurch Street one hundred of sparrowgrass, cost 18d.’

|

| Robert Southey |

In a letter to Coleridge dated July 23rd

1801, Robert Southey has,

“… sparagrass (it ought to be spelled so) and artichokes, good with plain butter, and wholesome.”

During the nineteenth

century, the correct name grew again in literary and polite usage and

sparrow-grass began to be seen as an illiteracy. In modern French it is asperge;

German, spargel; Dutch, aspergie; Spanish, esperrago.

|

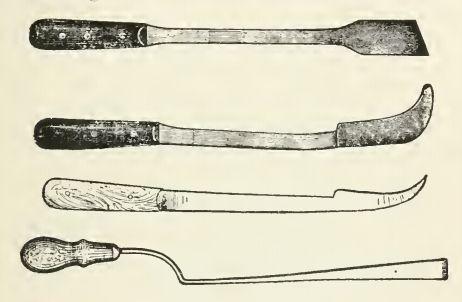

| Asparagus Harvesting Knives |

Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History (Book XIX), differentiates

between varieties of asparagus, claiming that the finest grew at Ravenna, and

that three stalks from there weighed one pound; he also says that the roots of

asparagus can be used to make wine. The Roman method of preparing asparagus was

to dry it and, when required, to quickly boil the dried shoots in water – the

Emperor Augustus had a favourite saying for when he wanted something done

quickly,

“Citius quam asparagi coquentur,”“Do it quicker than you can cook asparagus.”

|

| Asparagus |

The old herbals give asparagus as a remedy for toothache, with

the first mention of sparagi occurring in an Anglo-Saxon text on

Leechdom dating from about 1000.

|

| Asparagus - said by some to be an aphrodisiac! |

William Turner’s The Names of Herbes

(1548) differentiates between two types of asparagus, a common kind that is

grown in English gardens and a prickly type, which is found in the Italian

mountains. In 1555, Joannes Boemus wrote about the plants grown by the ‘Moors’

of North Africa,

“Their haue Cannes like vnto those of India, whiche may contein in the compasse of the knot, or iointe, the measure of ij. bushelles. Ther be sene also Sparagi, of no lesse notable bigguenesse.”The Fardle of Facions.

| ||

| "Well, What do you think of the dining-room, my dear?" "Why, Horace, there's hardly room to swing an asparagus stalk." |

Enjoy your asparagus while you may – the season ends, traditionally,

on Midusmmer’s Day.

|

| Asparagus |

Oh, and it is said to be a great hangover cure (not that

I’d know about that…).

No comments:

Post a Comment