In the years between 1827, when the first plates of

his Birds of America were printed, through to 1839, when John James

Audubon, with the assistance of James MacGillivray, completed the Ornithilogical

Biography, he spent his time alternately between England and America.

During his time in America, he travelled and drew, at a punishing pace;

“I am at work and have done much, but I wish I had eight pairs of hands, and another body to shoot the specimens; still I am delighted at what I have accumulated in drawings this season. Forty-two drawings in four months, eleven large, eleven middle size, and twenty-two small, comprising ninety-five birds.”

|

| J J Audubon - American Bald Eagle |

He would rise before dawn and begin working, sometimes in sessions of fourteen

hours at a spell, and would also go out into the wild to shoot specimens, which

he mounted with wires in life-like poses, attempting to draw and paint the bird

on the same day, and would work until about one o’clock in the morning, often

only sleeping for four hours, before rising again and repeating the same

pattern.

|

| J J Audubon - Bernicle Geese - Read more here |

There was pressure to keep producing the drawings in order to fulfil

his obligations to the subscribers, but it was a labour of love and Audubon

worked at such a pace because he enjoyed what he was doing, his enthusiasm for

the project drove his perseverance. When he spent the rest of his days engaged

in the other side of the business, obtaining further subscriptions or

collecting the fees, he dreamed of being back in the wilderness, left to

himself with his birds, and adding material to his great work.

|

| J J Audubon - Passenger Pigeons - Read more Here |

The Audubons

tried settling down in New York, but city life did not suit them and, in 1842,

they bought instead property on the Hudson River which they called Minnie’s

Land (it is now incorporated into New York and is known as Audubon Park). As

the years passed, Audubon was greatly helped by his sons, Victor and John,

(John Waterhouse Audubon became a noted naturalist in his own right), as they

undertook much of the administrative side of the enterprise, giving Audubon

more time to concentrate on his drawings.

|

| J J Audubon - Great Auk - Read more here |

When the octavo edition of Audubon’s

work was published, Victor oversaw the printing and John reduced the plates to

the required size with a camera lucida. In 1837, Audubon faced two

threats to the nearing completion of his work. The first was the result of his

own industry, for as he had spent so much time searching for specimens, he had

discovered new species that, in order to comply with his initial intent of

figuring every species of American birds, he was compelled to included them.

|

| J J Audubon - White Egret - Read more here |

However, he had, in his prospectus, fixed the edition to be of eighty parts of

five plates, a total of 400 plates. Many subscribers were not prepared to pay

for any additional plates, and Audubon was not prepared to compromise by

including plates that featured more than a single species each, but his only

other option was to issue a completely new, complete, edition.

|

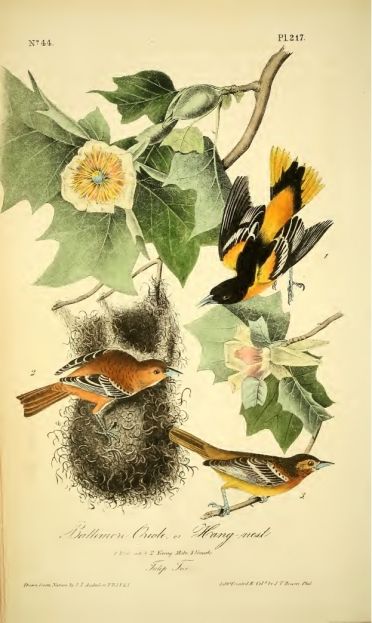

| J J Audubon - Baltimore Oriole |

He was also

forced to abandon his plan of including plates, at the end, that were intended

to show the eggs of all the birds. In the end, he extended the plates by an

additional seven parts, of thirty-five plates, by which he figured 489 American

species. The second problem was the economic crisis of 1837, which greatly

affected subscribers on both sides of the Atlantic, with many having no choice

but to cancel their subscriptions as they faced bankruptcy.

|

| J J Audubon - Blue Jays |

It had been an

ambitious undertaking in the first place and, in his heart of hearts, Audubon

must have known that a number of his subscribers would have had to cancel, for

whatever the reasons, over a period of ten years, even if they fully intended

to commit themselves to an outlay of about $100 per annum. Audubon himself

estimated that there were 120 incomplete editions in circulation when the work

was eventually completed.

|

| J J Audubon - Eider Ducks |

Still, on June 20th 1838, the final plate

of the Birds of America was published, completing the illustrations although it

would be two more years before the text was finished. It is a remarkable

undertaking, in size, scope and ambition, and is one of the most beautiful of

any printed book ever produced. The double elephant sized volumes require two

men to lift them, because of the weight and the size, and each print contains a

life-size depiction of its subject.

|

| J J Audubon - Roseate Spoonbill |

Audubon’s finished drawings were engraved

onto copper plates and for each impression, the metal plate had to be inked and

pressed individually, left to dry, and then painted in water-colours by hand by

teams of skilled colourists. At the time, chromo-lithography was a thing of the

future, and this was the only method of producing a work of this sort. As such,

it was tremendously expensive to make and to buy, and because publishers were

unwilling to undertake the costs of production, Audubon himself paid for the

books to be printed and coloured.

|

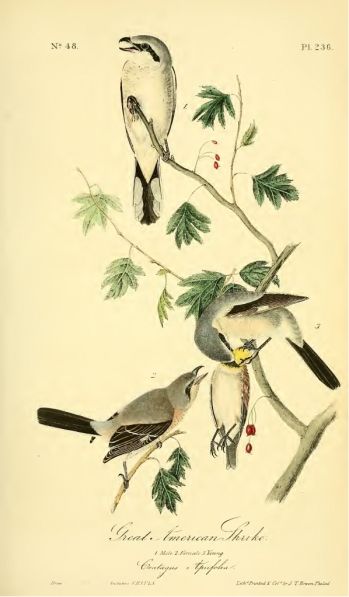

| J J Audubon - Great American Shrike |

It is estimated that he paid out over

$100,000 in production costs over the twelve years it took to complete the

work. It is thought that 120 copies of the complete first edition still exist,

and to give you some idea of their worth, a complete copy sold in 2012 for $7.9

million.

Tomorrow – Beasts, not Birds.

No comments:

Post a Comment