You could never accuse Charles Waterton of

inconsistency. Over five years, he sent nineteen articles to the Magazine of

Natural History, attacking Audubon, his friends, his supporters, his

associates and there is every chance, given time, he would have got around to

having a go at his bootmaker or his dog. Some of the criticism is measured and

considered, but the majority of it comes across as the crazed ramblings of an

eccentric English country squire. Which comes as no great surprise, because

that’s just what they are.

|

| Charles Waterton |

Waterton’s Roman Catholic family had held great

tracts of land in Yorkshire prior to the Norman Conquest and, as Waterton puts

it in his memoir,

‘… things had gone swimmingly for the Watertons,’

up

until the days of King Henry VIII, when that King fixed his eyes on a buxom

lass but was refused permission to marry her by the Pope, so he ‘became

exceedingly mischievous’ and caused himself to be made head of the Church,

whereupon,

“… he suppressed all the monasteries, and squandered their revenues amongst gamesters, harlots, mountebanks, and apostates.”

|

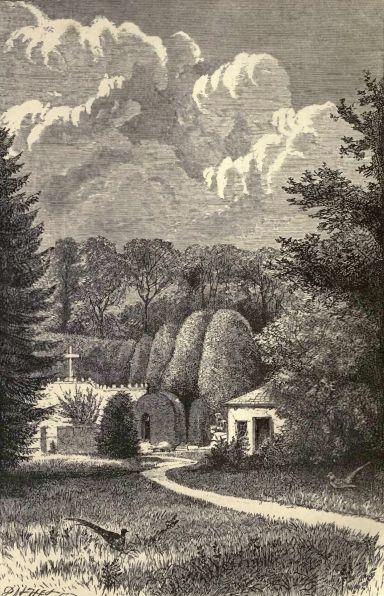

| Walton Hall |

After their

Reformation, the new religionists made the Watertons pay a penalty of twenty

pounds a month for refusing to hear a married parson read the prayers in a

church stripped of its altar, its crucifix, its chalice and its tabernacle.

Waterton’s grandfather was jailed at York for supporting the hereditary right

of kings, in the person of Bonnie Prince Charlie, and had his horses

confiscated by the magistrates, although they offered to sell him one back,

provided it was worth less than £5 – the laws forbade Catholics from owning a

horse worth more than that amount – and when ‘Dutch William’ took the

throne, that ‘sordid foreigner’ doubled the taxes paid by Catholics.

|

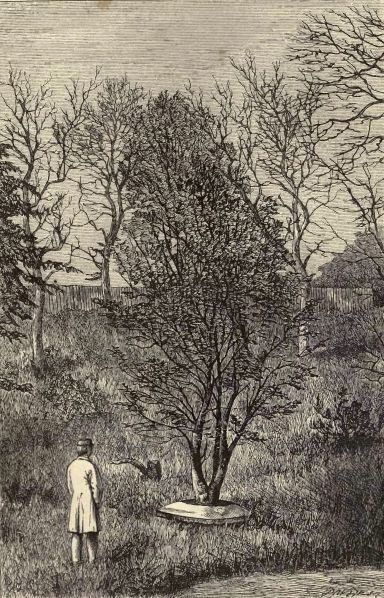

| Stonyhurst College, Hurst Green, Lancashire |

In

1796, young Waterton was sent to school at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire,

which had just been signed over to the Jesuits, making Waterton one of the

earliest pupils to attend. In the woods and fields around Hurst Green, Waterton

was able to give his love of nature its full rein, and the Jesuits encouraged

his interests as well as inculcating a love of literature in their charge.

|

| Gateway at Walton Hall |

His

master, Father Clifford, predicted that nothing would keep Waterton at home and

that he would travel to many far distant lands. Clifford also made him promise

that he would never drink wines or spirits, a promise he kept throughout his

life, (when, in 1824, he built a wall, three-miles long and nine feet high,

around his Walton Hall estate, at a cost of £9,000 (£2.4 million in today’s

money), he said he paid for it with ‘the wine I do not drink’).

|

| The Grotto, Walton Hall |

When he

finished his time at Stonyhurst, he returned to Walton Hall, where he spent the

best part of a year riding and fox-hunting, before he went to Spain, in 1802,

to visit two of his uncles, and where he experienced pestilence and an

earthquake.

|

| Waterton and the Vigour of Nature |

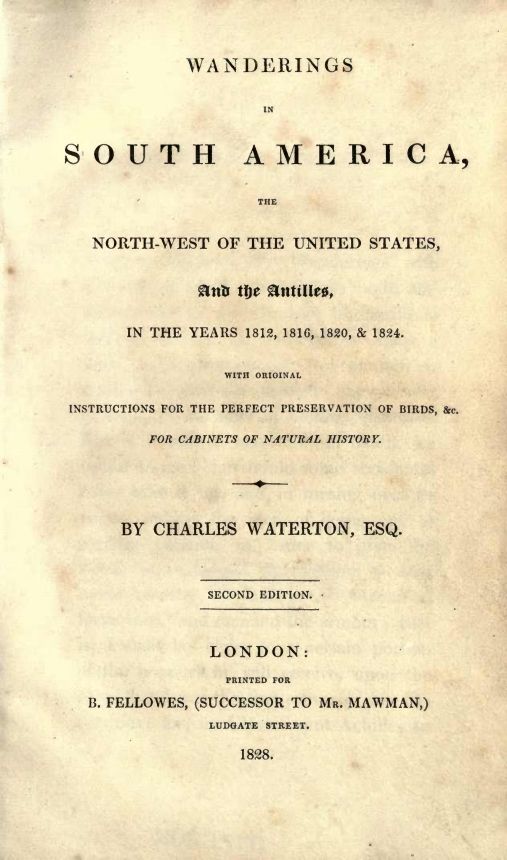

In 1804, he travelled to Demerara, where another uncle had a

plantation, and delighted in the natural history of Guiana, and after returning

to England in 1806, following his father’s death, he made four more journeys to

the Americas, which he wrote about in his Wanderings in South America, the

North-West of the United States and the Antilles (1825).

|

| Charles Waterton - Wanderings in South America, the North-West of the United States and the Antilles - 1825 (2nd Ed. 1828) |

The book was very

popular at the time, and in it Waterton foregoes the guide-book style of travel

writing and instead gives detailed descriptions of the flora and fauna he

encountered, providing, for instance, the first accounts of the giant

ant-eater, the sloth and the toucan.

|

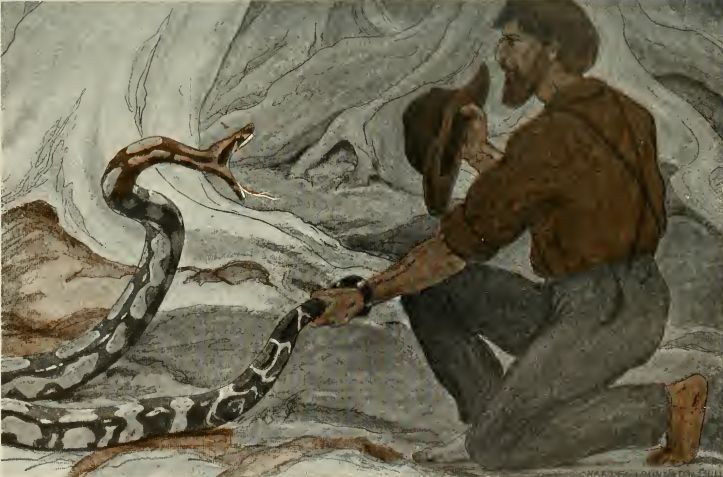

| Wrestling a Cayman |

Perhaps the most famous incident in the Wanderings

is his capture of a live cayman, ten and a half feet in length, which was

hooked in a river and onto which Waterton threw himself, wrestling its forelegs

behind its back,

‘thus they served me for a bridle … he continued to plunge and strike, and made my seat very uncomfortable. It must have been a fine sight for an unoccupied spectator.’

The creature was taken back to

Waterton’s camp where, after breakfast, it was killed and dissected. In another

incident, when surprised by a boa, Waterton put his fist into his hat and

punched the snake in its open jaws.

|

| Punching a Snake |

When he returned to Walton Hall, he

published a collection of writings Essays on Natural History, chiefly

Ornithology (1838), and established what is regarded as the world’s first

nature reserve, forbidding hunting and fowling on his estates. He was also the

inventor of the artificial nesting box, which he placed in the trees around

Walton, and in buying a telescope, with which to watch the birds on his estate,

he has a claim to be the world’s first birdwatcher.

|

| Charles Waterton - Essays on Natural History, chiefly Ornithology - 1838 |

Although he hated the term,

he became known as the ‘eccentric squire’, which was probably deserved –

he had a habit of ducking below the dinner table and biting his guests’ legs,

in the manner of a dog. The fashion of the day was for men to wear their hair

long – Waterton wore his hair closely cropped. When in Rome, he climbed to the

cross that served as a lightning conductor on the dome of St Peter’s basilica,

and left his gloves upon it; when Pope Pius VII asked him to remove them, he

climbed back up again and did so.

|

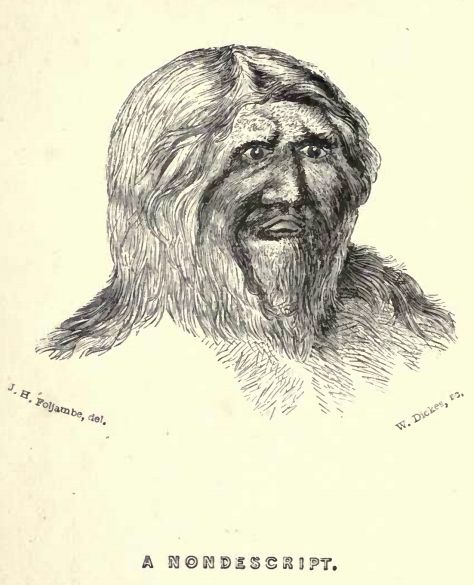

| Walton Hall estate |

In an attempt to ‘navigate the atmosphere’

(i.e. fly), he jumped from the roof of an outhouse, only to hit the ground with

a ‘foul shak.’ He was a skilled taxidermist (the final chapter of his Wanderings

is as good an introduction to the art as you are ever likely to find), and he

prepared the skin of a red howler monkey, which he called the ‘Nondescript’,

said by some to be a caricature of an enemy, Treasury Secretary J R Lushington.

|

| The Nondescript |

But it was not all madness. When in Guiana, he taught taxidermy to a black

slave, John Edmonstone, who moved first to Glasgow and then Edinburgh when he

gained his freedom, and where he in turn taught taxidermy to the University

students, including one Charles Darwin. Both Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

acknowledged that, as boys, they were inspired to study natural history after

reading Waterton’s Wanderings.

|

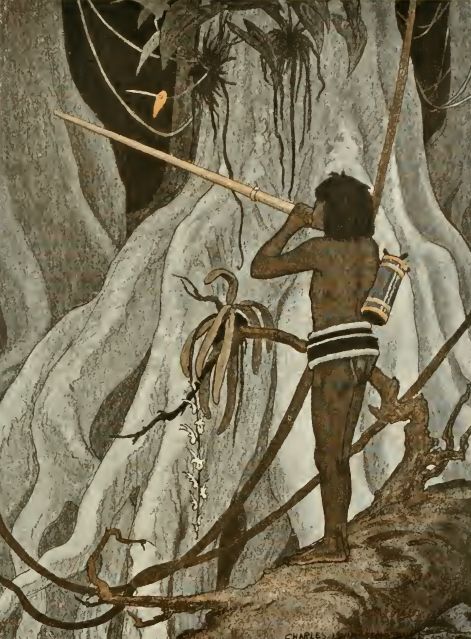

| Blowpipe |

He introduced the valuable medicine

curare into England, which he had seen the peoples of South America using in

their blowpipes, and also introduced the Little Owl into this country. In 1829,

at the age of 47, he married Anne Edmondstone, who was 17 at the time. She died

in childbirth a year later, Waterton blamed himself and, as penance, thereafter

slept on the bare floor with an oak block as a pillow. He can also lay claim to

be one of the first environmentalists, as he fought and won a legal battle

against a soap manufacturer whose factory was polluting the waters surrounding

Walton Hall.

|

| Waterton's Grave |

In spite of his wrestling caymen, punching boas, surviving

earthquakes and plagues, he died at 83, when he tripped over a briar root,

broke his ribs and injured his liver. He was buried between two oak trees on

his Walton estate.

|

| Walton Hall |

Waterton’s only son, Edmund, failed to keep up his father’s

works. He opened up Walton to shooting parties, in an attempt to clear his debts,

and eventually sold the estate to Edward ‘Soapy’ Simpson, the same polluting

manufacturer that his father had defeated in the legal case.

No comments:

Post a Comment