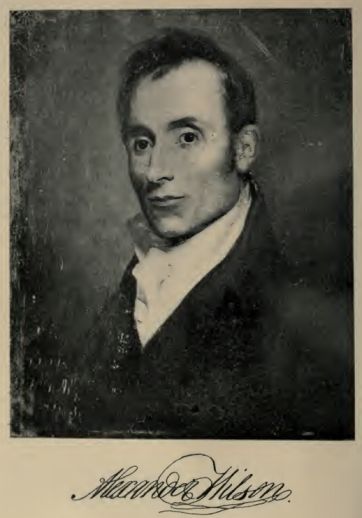

He was not above middle height, with a gaunt face

dominated by a hooked nose and high cheekbones, dressed in a short coat,

trousers and waistcoat of grey cloth that look out of place in Louisville,

Kentucky. Under his arm, he carries two books and he approaches the table where

John James Audubon sat, in the counting house of his general store.

|

| Alexander Wilson |

His name is

Alexander Wilson, originally from Paisley in Scotland, but he had emigrated to

America in search of a better life, like so many of his countrymen, and now he

was looking for subscribers for his book about American ornithology, samples of

which he carries with him. Regardless of the cost, Audubon is keen to add his

name to the list of subscribers, until his business partner, Frederick Rozier,

intervenes. Speaking in French, he says to John,

“My dear Audubon, what induces you to subscribe to this work? Your drawings are certainly far better; and again, you must know as much of the habits of American birds as this gentleman.”

|

| Alexander Wilson |

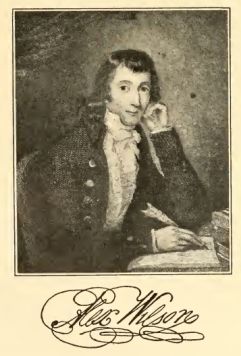

We don’t know if Wilson understood the words, but he certainly

understands the change in Audubon’s demeanour, as he lays his pen aside. His

friend’s encomiums and his own vanity have put an end to his subscription, and

Wilson’s crest falls further when the Frenchman takes out a portfolio of

drawings of his own.

|

| Illustration from Alexander Wilson - American Ornithology |

Birds. So many birds. He shudders in trepidation as he

asks if the artist intends to publish and allows himself a sigh when he replies

in the negative. He asks if he might borrow some of the drawings during his

stay in Louisville, and accompanies Audubon on a collecting trip of species he

has not yet seen. Audubon suggests a correspondence, that Wilson may like to

include some his drawings in his opus, all he asks is that he receives

credit for the works used. Five days later, he leaves for Philadelphia, where

Audubon later visits him. He is received cordially, but there is no mention of

birds, the drawings or the letters, and they part, never to meet again.

|

| Alexander Wilson - Title Page - American Ornithology |

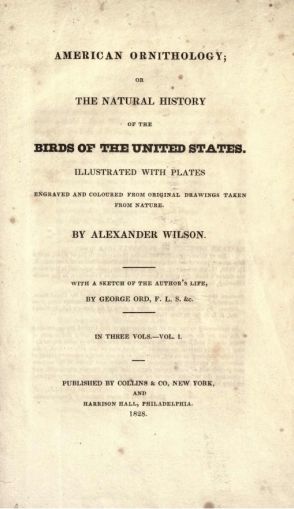

But

Audubon is surprised, if not shocked, when he later reads in volume nine of

Wilson’s American Ornithology,

“I bade adieu to Louisville, to which place I had four letters of recommendation, and was taught to expect much of everything there; but neither received one act of civility from those to whom I was recommended, one subscriber, nor one new bird; though I delivered my letters, ransacked the woods repeatedly, and visited all the characters likely to subscribe. Science or literature has not one friend in this place.”

Wilson died, unexpectedly, in 1813, and there would be further controversy as

his executors saw to the publication of his works, to which I will return

later. Meanwhile, the once prosperous Audubon and Rozier business began a

downturn in its fortune, as competition moved into the area, with other stores

being opened, and the economic repercussions of the political policies taken

prior to, and during, the Revolutionary War began to be felt. Trade embargoes

affected European imports, and Audubon and Rozier felt that a move further down

the Ohio river might prove to be advantageous, so they took the hundred and

twenty-five mile journey to Henderson, where they opened another store. It was

an ill-judged move, as the country was so sparsely populated that they only

sold the most basic of provisions, largely guns and fishing lines, and another

move was proposed, to St Geneviève on the Mississippi river.

|

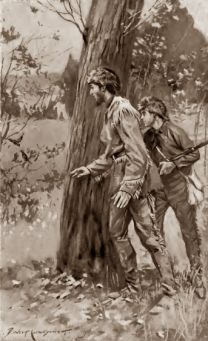

| Out Birding in the Wilds |

Audubon and Rozier

set out on a raft for the convergence of the Ohio and Mississippi, but they

became stranded in the winter ice, and laid up in the wilderness, hunting game

for food and making the acquaintance of the local indigenous people, from whom

Audubon learned a great deal about the flora and fauna. With the spring thaw,

they proceeded to St Geneviève, where they had a little success selling whisky

they had bought for 25c per gallon for $2 per gallon, but Audubon had no love

for the French-Canadians of St Geneviève, found the place dirty and noisy, and

eventually he and Rozier agreed to part, with Rozier, who had married a local

woman, buying out Audubon’s share of the stock. Audubon bought a horse and

returned to Henderson, where his wife and infant son had stayed, narrowly

avoiding being murdered by drunken Indians along the way.

|

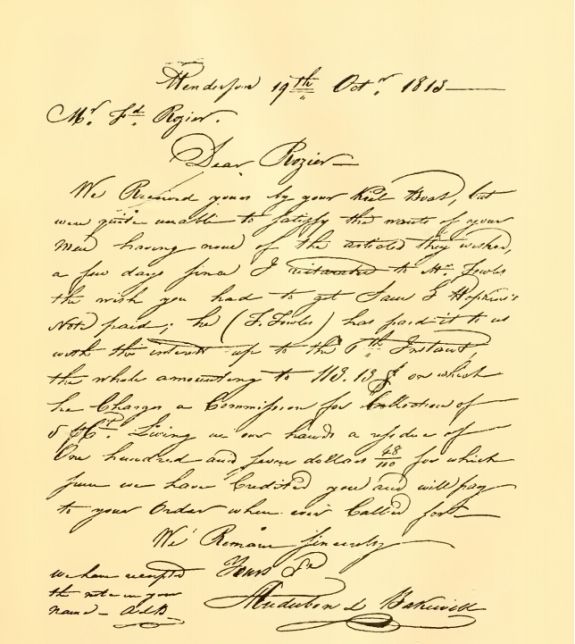

| Letter from Audubon to Rozier |

Shortly after his

return, his second son was born, and in November 1813, an earthquake struck the

area around Henderson. Audubon entered into a business partnership with Thomas

Bakewell, his brother-in-law, selling flour, lard, pork and other foodstuffs on

commission, but this enterprise faltered with the outbreak of the 1812 war, but

Audubon persevered and made a success of small store located in a log cabin in

Henderson.

|

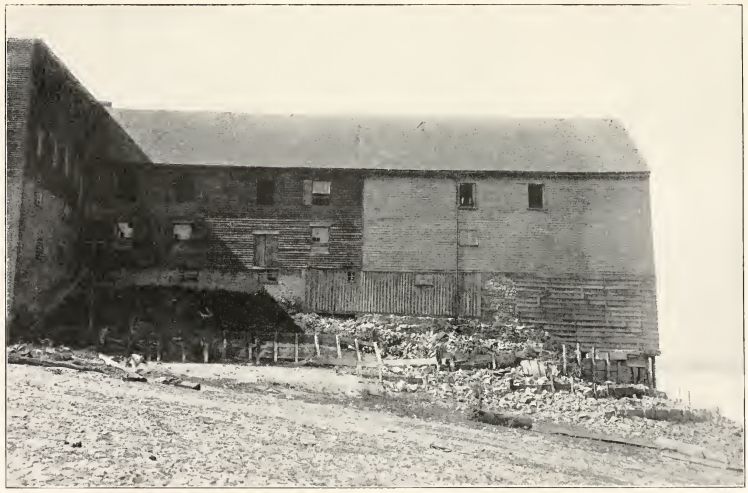

| The Mill, Henderson |

He was persuaded by Bakewell to invest in a steam-driven mill, in

partnership with an Englishman, Thomas Pears, with whom had had previously

worked in the Bakewell family offices in New York. The mill had a grist mill

and a steam driven saw, and the three were certain that they would make their

fortunes, which they would had it not been for the simple reason that there was

no grain grown around Henderson and there was no lumber trade, meaning that for

most of the time, the mill stood idle. Audubon received news from France that

his father had died a year previously, leaving the estate there to him (which

he eventually signed over to his sister, Rosa), and seventeen thousand dollars.

However, by the time Audubon obtained the proof of identity required by the

merchant holding the money, that merchant had died in insolvency, and the

inheritance was lost.

|

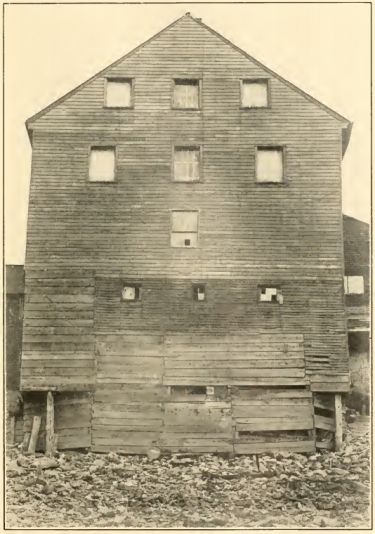

| Another view of the Mill |

The mill proved to be a money pit, and eventually went

broke, ruining all involved with mounting debts. Audubon, his wife and two sons

left Henderson in the clothes they stood up in, with only a gun, a dog and his

bird drawings, and took lodgings with a relative in Louisville, where he eked

out a living selling portraits to the locals for $5 per picture.

Tomorrow – Changes all round.

No comments:

Post a Comment