As John James Audubon made his way back home to

America, where George Ord and his Philadelphians were busy picking over his Birds

of America, their criticism of him crossed the Atlantic in the other

direction, where Charles Waterton picked it up and launched an anti-Audubon

campaign of his own in England. On the face of it, Audubon and Waterton should

have been natural allies but, like George Ord, Waterton could not bear anyone

who dared to contradict him or his opinions.

|

| Charles Waterton - Wanderings - 1825 (2nd Ed. 1828) |

In his Wanderings in South America,

the North-West of the United States and the Antilles (1825), Waterton had

described how vultures used their olfactory sense to locate carrion.

|

| J J Audubon - Account of the Habits of the Turkey Buzzard - Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal - 1827 |

On

December 7th 1827, Audubon’s paper Account of the Habits of the

Turkey Buzzard (Vultur aura), particularly with the view of exploding the

opinion generally entertained of its extraordinary power of Smelling was

presented to the Wernian Society of Natural History in Edinburgh, a paper that

directly contradicts Waterton’s account.

When Perceval Hunter defended

Audubon’s views in the Magazine of Natural History of 1833, it was too

much for Waterton’s pride, he could not do other than reply. So, and with a

line from Virgil’s Æneid, Waterton put his first shot across Audubon’s

bows.

Quis novus hic nostris successit sedibus hospes?Who is this new guest who approaches our seat?

Who indeed? This American has arrived in our

midst, unknown in his own country, and is immediately lauded as

‘an ornithological luminary of the first magnitude’.

How can this be?

“His drawings are out of the question, they being solely a work of art.”

|

| Charles Waterton - On the Biography of Birds - Magazine of Natural History - 1833 |

So, if

it is not the drawings, it must be the words. Waterton looks at Audubon’s

account of the Vultur Aura, and most certainly finds it wanting;

“[The] production is lamentably faulty at almost every point. Its grammar is bad; its composition poor; and its statements are … unsatisfactory.”

A

paper as poor as this cannot possibly be the cause of the praise being heaped

upon Audubon’s shoulders, so perhaps his reputation is being made through the Ornithological

Biographies? Now these, Waterton admits, may have some literary merits,

however much they lack in ornithological merit. How can this be? Well, of

course, Waterton deduces, they must not be the production of the same pen! Does

not Audubon himself admit in his introduction that he was ‘assisted’ by

a friend in the scientific details of the work? Maybe we should take the

current recommendations to read ‘Mr Audubon’s’ works, if indeed they are his

works, with a grain of salt?

|

| J J Audubon - Turkey Vulture - Birds of America |

Indeed, when we compare the paper on the Turkey

Vulture with the style of the Biographies, there can only be one reasonable

conclusion – the backwoodsman Audubon may have written the first, but his

scientific ‘assistant’ has most definitely written the latter.

"[T]he correct and elegant style of composition which appears throughout the whole of the Biography of Birds cannot possibly be that of him whose name it bears; we have undoubted facts to prove that it is far beyond the reach of Audubon.”

It is clear, if you can’t trust him when he says he has written

the book, how can you then trust what that book contains?

There was something

that Charles Waterton did not know. He didn’t know that when John James Audubon

returned to America, his place in England was taken by his son, Victor, who

took up his own pen in defence of his father.

|

| Victor Audubon - Letter to the Magazine of Natural History - June 7 1833 |

In a letter to the Magazine of

Natural History dated June 7th 1833, he thanks Mr Waterton for

his good grace in holding back his criticism for two whole years and waiting

until his father had left these shores before attacking his reputation, and he

assures him that, when he returns and if he thinks it worth his while, he will

be more than willing to put Mr Waterton right. Another letter, dated June 10th,

was printed directly after Victor Audubon’s in the same issue of the Magazine.

|

| Magazine of Natural History - 1833 |

This was from Robert Bakewell, the nephew of Lucy Audubon’s grandfather, and is

a masterpiece of nineteenth century English understatement. It is the case, in

the biographies of the seekers after scientific truths, that when they return

from their expeditions, they often find that the jealous and the envious have

been at work undermining their fair won fame. Mr Audubon was currently away, in

Labrador, gathering information on the ornithology of that region, and would be

dismayed by the imputations being made by Mr Waterton, the author of the

always-amusing Wanderings.

|

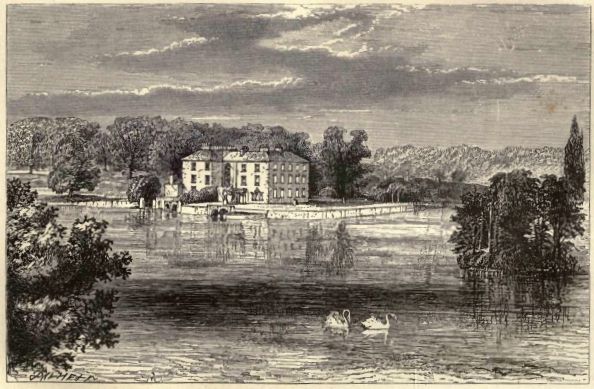

| Charles Waterton |

Now, far be it from Bakewell to point out

that Mr Audubon was, even then, out in the wilderness, alone and dependent of

his gun for his sole protection, suffering the privations and dangers in order

to make his living, whereas Mr Waterton wrote from the comfort of a tranquil

English mansion, surrounded by lush paternal acres, and when he went into the

wild himself, he departed from his family’s rich plantation, accompanied by his

slaves and attendants.

|

| Walton Hall, Wakefield - Charles Waterton's family seat |

Nor should it be mentioned that until the age of

seventeen, Mr Audubon spoke only French, and would it not only be natural for

him to ask his wife, an educated English lady from a good family, to cast her

eye over his prose before he sent it off for publication? And might it also be

the case, that he might ask a scientific friend to perform a similar task, just

to verify his facts? He writes with reluctance, and begs Mr Waterton’s pardon

but, he asks, might that gentleman’s own Wanderings stand up to concerted

criticism?

It is much safer to put the foot into a hornet's nest, than provoke a swarm of naturalists.

I leave it to you to decide if that is an

observation or a threat.

No comments:

Post a Comment