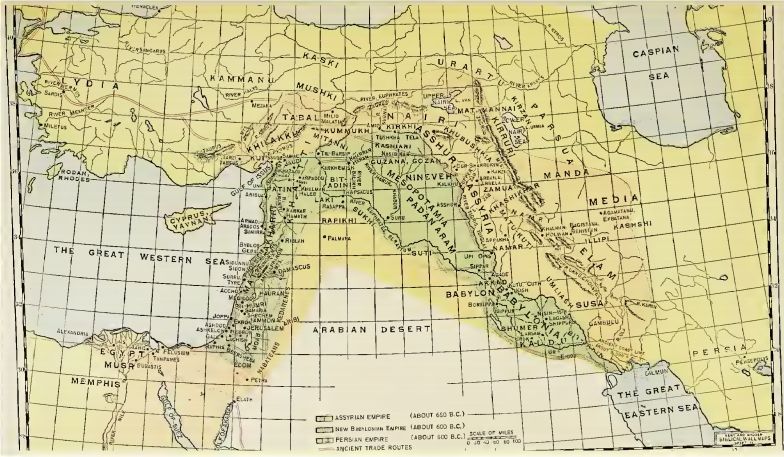

Five thousand years ago, in the cradle of Western

civilization that lay between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates that we now call

Iraq, the ancient Babylonians and Sumerians held their New Year celebrations at

about the time of the Spring Equinox. These Mesopotamians (a word that means ‘[dwellers

of the land] between the rivers’), the Babylonians to the north and

the Sumerians further to the south called this festival, respectively, Akita

and Zagmuk (or Zakmuk).

|

| Map of Mesopotamia |

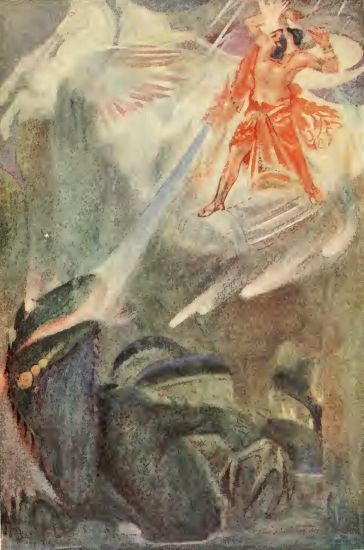

The final days of the year were a time of

decay and death, as the very year itself withered and died, and thoughts turned

to the departed. The terrible chaos goddess Tiamat threatened to destroy

the world and all its inhabitants; she was a sea-monster, born of the marriage

of fresh and salt water, who gave birth to a generation of young gods, on whom

she later declared war. From these young gods, one rose to lead the fight

against Tiamat and defeated her, thus saving the world.

|

| Marduk & Tiamat |

He was Marduk, a

young Sun god, whose name comes through amar-ud - ‘Youth of the Sun’,

and maru Duku – ‘Child of the Holy chamber’, who was also called Bêl which

means ‘Lord’ and may be known to Bible readers as Ba’al (when Bêl is mentioned,

it always refers to Marduk). Marduk fought against chaos and was killed,

spending time in the underworld before being resurrected, returning to life to

defeat the forces of evil and so becoming the King of the gods.

|

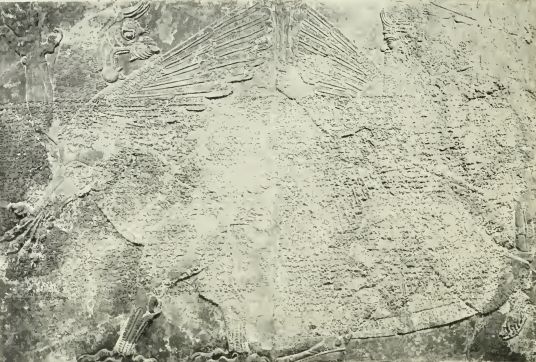

| Limestone bas-relief of Marduk and Tiamat |

He was a

fertility god and a grain god, his death symbolised the death of the sun in

winter, his sojourn in the underworld is the grain lying dormant in the ground,

and his return is the arrival of spring, new growth and green leaves.

|

| Clearer image of the above relief |

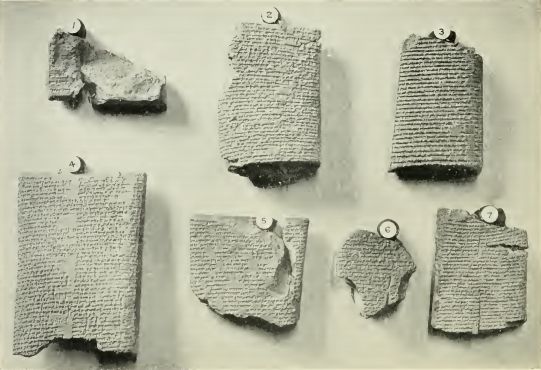

The feast

of Akita (and Zagmuk) lasted for twelve days; on the first three

days, the priests would come to the high Temple of Marduk in Babylon, the Ésagila,

and offer prayers of lamentation and supplication. These prayers were repeated

on the fourth day, when the Enûma Eliš, the great Babylonian Epic of

Creation, was recited, telling the story of Marduk’s victory over Tiamat.

|

| Cuneiform tablets of the Enuma Elis |

On

the fifth day, the king of Babylon came to the Ésagila, was stripped of

his crown, robes and regalia, and was humiliated by the High Priest, who struck

him in the face, symbolising submission before the greater power of the god,

after which his crown was returned, symbolising the god’s approval of his royal

and civic roles.

|

| The Tower of Babel |

Marduk is then captured by the evil gods and held prisoner by

them, in the Etemenanki, a seven-storey ziggurat (identified in the Torah and

the Bible as the Tower of Babel), where he awaits the arrival of his son, Nabu.

He arrives on day six, symbolised by a great, formal procession of the King and

the citizens of Babylon to the Ésagila, and on day seven, Nabu frees his

embattled father.

|

| Nabu, son of Marduk |

The eighth day saw the gathering of the statues of the gods

in the hall of Destinies, where they bestow their powers on Marduk, confirming

his primacy over them all. A victory procession to the House of Akita, situated

outside the city walls, took place on the ninth day, as the populace celebrated

Marduk’s defeat of Tiamat, and on the tenth day, Marduk returns to earth during

the night and marries the goddess Ishtar, their roles acted by the King of

Babylon and the High Priestess of the Ésagila. The eleventh day sees the

return to the hall of Destinies, where the gods and Marduk renew their covenant

with mankind before they return to Heaven, and on the final day, the statues of

the gods were returned to their places in the Ésagila and the king would

be slain, so that his spirit could assist Marduk – although, in reality, a

criminal would be elected as a proxy king and killed in place of the true king.

|

| Marduk slays Tiamat |

We can see here clear parallels here with the Lord of Misrule, a substitute

king who takes over the responsibilities of the real king at the festival time,

as well as story of Jesus and Barabbas in the New Testament, (Barabbas means,

literally, ‘Son of the Lord’), and the wide-spread legends of the dying god who

returns to life. The twelve days of Zagmuk are the origins of our twelve days

of Christmas, although moved from the Babylonian New Year to our New Year, and

they may well be the intercalary adjustment of 11.25 days needed to reconcile

the 354 days of the lunar year with the 365.25 days of the solar year.

No comments:

Post a Comment