When Alexandrina Victoria was born to Edward, Duke

of Kent and his German wife, Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, in

1819, there were few who would, or could, have seen how the course of her life

would run. Edward was the fourth son of King George III and every reasonable

expectation was that one of his elder brothers would provide the heir to the

British throne, but when they all died without legitimate, surviving issue,

Victoria became heir presumptive.

|

| Victoria as a girl |

In 1830, a Regency Act was passed which made

provision for Victoria’s mother, the Duchess of Kent, to act as Regent should

her uncle, the reigning King William IV, die whilst his heir was still a minor.

Victoria came of age in May 1837 and the King died in June of the same year,

thus avoiding the need for the Regency, and the young, new Queen was greeted

with mixed feelings.

|

| Victoria as a girl |

Many felt sympathy for the girl, raised in suffocating

seclusion by a domineering, manipulative mother and her scheming lover, Sir

John Conroy, but she was also the next in the line of Hanoverian monarchs, a

deeply unpopular House of German philanderers, wastrels and rakes, (her

predecessor, William IV, had had at least ten, and maybe more, illegitimate

offspring, who were regarded as rapacious, opportunistic drains on the public

purse, and his predecessor, George IV, was an even more notoriously debauched

spendthrift).

|

| Queen Victoria Coronation Portrait |

In the early years of her reign, the majority of people were

willing to give the small, slim girl-queen the benefit of the doubt and many

were won over by her quiet dignity, her modesty and obvious abilities in the

offices of state. There was gossip that Lord Melbourne, the Whig prime minister

and her advisor, had untoward influence and maybe more over this young monarch

and tongues wagged freely, as they will, but things came to a head in 1839,

when it was rumoured that Sir John Conroy, lover of Victoria’s mother, had

seduced a lady-in-waiting, Lady Flora Hastings, in a carriage on the return

journey from Scotland.

|

| Lady Flora Hastings |

Lady Flora loudly denied all this but as her waist began

to swell, the fingers pointed and the accusations flew, and yet Lady Flora

continued with her declarations of innocence. Sir James Clark, the court

physician, suspected that the rumours were true and passed his suspicions on to

Lady Portman, a royal lady-in-waiting, who in turn informed the Queen. In an

enormous error of judgment, the Queen, who hated both Conroy and the ‘odious’

Hastings, ordered a medical examination of the Lady, who at first refused to

submit but then graciously agreed, and was found to still be a virgin. Victoria

privately apologised to Lady Flora and thought that to be the end of the

matter, but when the Lady died a few months later, a post mortem revealed that

a large liver tumour had distended her abdomen, giving the appearance of

gravidity, something which the medical examination had overlooked.

|

| Young Victoria |

Conroy, the

Hastings family and the Tory opposition continued to use the case as a weapon

against Melbourne and the Whigs; they demanded the removal of Sir James Clark

but an obstinate Queen refused to act and maintained a stony silence. Letters

appeared in the press, reparation was demanded and apologies called for, all to

no avail. The socially influential Hastings family, who were Tories, turned the

feelings of the royal court and the public tide of opinion against the Queen,

with Lady Flora being portrayed as the ‘victim of a depraved Court’.

Victoria was seen to be dabbling in party politics; she liked Melbourne and his

Whigs and disliked the ‘cold, odd man’, Sir Robert Peel and the Tories.

|

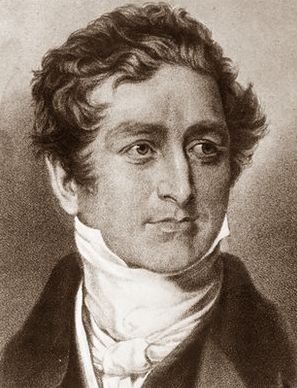

| Sir Robert Peel |

She wanted Melbourne to stay at the Palace and to continue to advise her, and

her behaviour was seen as unconstitutional, irregular and unbending. There were

some who began to refer to her as ‘Mrs Melbourne’, it was reported that the

Duchess of Montrose had hissed at her in the Royal Enclosure at Ascot, in

public she was booed and jeered, and the coach she sent to the funeral of Lady

Flora Hastings was stoned as it passed to the cemetery. A second crisis

developed at the same time, when the Whigs and the Tories clashed over the

question of slavery in the colonies. The Whigs sought to implement earlier Acts

of Parliament that would abolish slavery, a move opposed by the Radicals and

the Tories (and the plantation owners of Jamaica), and a Bill to remove

constitutional and political power of the slave owners was opposed in the

Commons.

|

| Lord Melbourne |

Melbourne resigned in opposition to the vote and Victoria invited Peel

to form a government but then Peel insisted that the Whig ladies of the Royal

Household were replaced by Tory equivalents. These Whig ladies were Victoria’s

friends and confidantes and she saw no reason why they needed to be replaced;

Peel insisted, Victoria refused, Peel demanded, Victoria dug in her heels and

the Duke of Wellington was sent for. Wellington claimed he was too old and deaf

to take charge and advised Victoria to acquiesce to some small changes but

Victoria was not about to alter her decision.

|

| Young Victoria |

She was the Queen, she ruled the

Royal Household and she alone decided who would be her Ladies. Peel declined to

form a government and Melbourne and the Whigs returned to power but although

many sided with the Queen and felt it was their gentlemanly duty to do so, many

others felt that her petulance was just that old Hanoverian selfishness wearing

a different hat and that she had irreparably damaged her position. What the

girl obviously needed was the firm hand of a husband to keep her in order.

No comments:

Post a Comment