The Old Testament writers were inordinately fond of

wandering. There are people wandering about all over the place. After Cain

slays Abel, he wanders off to the east of Eden, until he comes to the Land of

Nod where he eventually builds a city called Enoch, after his son, borne to him

by his sister, Awan (if Adam and Eve were the only man and woman created by

God, there was bound to be some unsavoury jiggery-pokery going on at some stage

in the proceedings). The majority of the book of Exodus is taken up with

assorted wanderings (as you might expect, given its name). King David does his

own fair share of wandering hither and thither. And so on, and so on. If there

is a wilderness to be found, it’s an even money bet that there will be somebody

wandering off into it.

|

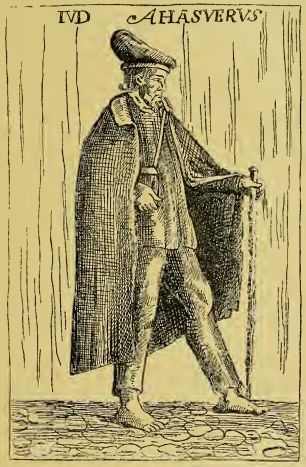

| A Jew wandering |

Given that Christian traditions form a sizeable slice of

Western civilisation, it is no surprise that legends of wanderers also feature

prominently in it. Joseph of Arimathea gave up his sepulchre for the body of

Jesus and so had no resting place, thus he wandered, coming at last to

Glastonbury. St James emerged from the rock that had encased his martyred body

and wandered in Spain, where he led the Spanish against the Moorish invaders.

St John did not rest in his tomb at Ephesus, he made pilgrimages instead,

wandering to England where King Edward the Confessor gave him a golden ring. St

Peter also wandered to England, where he presented the first abbot of

Westminster with a miraculous fish. The Wandering Jew was in good company and

not alone in his wanderings.

|

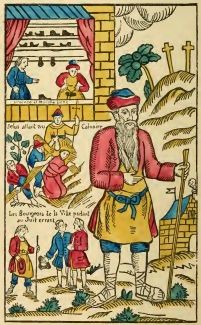

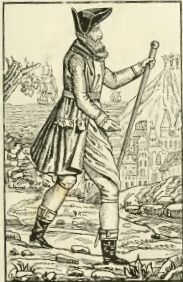

| The Wandering Jew |

It is unusual, in the light of the usual European

anti-Semitic sentiments, that the Wandering Jew is usually well received and in

many cases it is very unlucky to treat him badly. The general feeling appears

to be that the poor man has already suffered enough with the terrible fate

cursed upon him and deserves to be treated with sympathy and charity. In an

article in Notes and Queries (December 29th 1855), it is

related how, on a cold winter’s night, a cry might be heard in the darkness,

“Water, good Christian! Water for the love of God.”

Looking out, you would see an

old, bearded ancient and you would be wise to supply him with a drink. He

remembers kindnesses and will often return to pay back the deed when your need

is at its greatest.

|

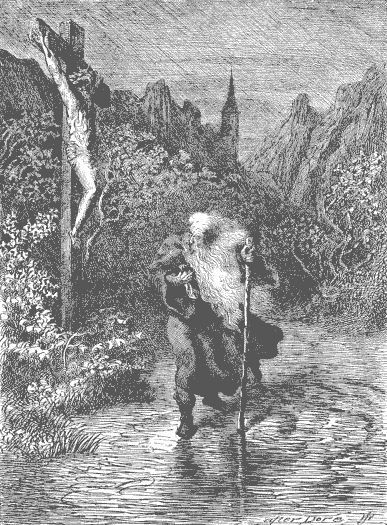

| Gustave Dore - The Wandering Jew |

A story from 1658 tells how an old man, Samuel Wallis of

Stamford, who was suffering from a deep consumption and beyond the help of

doctors, was reading one evening when he heard a knock on the door. Answering,

he met a tall, bearded ancient who said,

“Friend, I pray thee, give an old pilgrim a cup of small beere.”

The man was invited in and given a drink and

when finished he said to Wallis that he seemed to him to be ill. Wallis

explained his ailment and the ancient man told him which herbs he needed to

pick and how to prepare them and that, if done, would cure him after twelve

days. Wallis followed the instructions and recovered and went on to live for

many more years. He had been visited, he said, the Wandering Jew.

|

| Green Plover |

Another story

from Notes and Queries (September 30th 1871) tells how a

traveller met an old man on a Lancashire moor, who told him that a covey of

plovers flying overhead were ‘the whistlers or the wandering Jews’.

Pressed for information, the man said that the plovers held the souls of those

Jews who had assisted at the crucifixion and were doomed to fly forever,

bringing bad luck to any that heard them. When the traveller returned to the

road he found that he had missed the coach back to his lodgings and faced a

walk of many miles; the old man was quick to remind him of the fate of those

who heard the whistlers, (I have written more about this here).

In 1799,

William Godwin published St Leon, his second Gothic novel (a kind soul

really ought to have advised him to call it a day after his first attempt), in

which a feeble, emaciated and pale old stranger imparts the secret of eternal

youth and bestows the philosopher’s stone to the eponymous anti-hero. It may be

that St Leon played a small part in inspiring Godwin’s daughter’s novel Frankenstein

and this daughter, Mary, was later to marry Percy Bysshe Shelley, one of

whose early works was a four-canto effort called The Wandering Jew, (the

least said about which, the better).

|

| George Croly - Tarry Thou Till I Come |

In 1828, the Wandering Jew wanders into

George Croly’s Tarry Thou Till I Come, or Salathiel, the Wandering Jew,

a truly awful doorstep of a book that attempts to place the Passion in an

historically accurate setting and fails miserably as the enthusiastic zeal of

the author to proselytise at every available opportunity collapses in a flurry

of superfluous exclamation marks. It really is one of those dreadful, mawkish

nineteenth century triple-deckers that shoehorns a moral into every incident, a

message into every monologue and a metaphor into every other blessed thing – it’s

like the very worst of Thought for the Day with added schmaltz stirred

in with the bendiest bough broken off the sentimentality bush.

|

| Eugene Sue - The Wandering Jew - 1846 |

And the horror

doesn’t stop there, as the French got their paws in the pudding when Eugène Sue

gave the world his Le Juif Errant (The Wandering Jew) between

1844 and 1845, in a modest ten volumes that some idiot or other saw fit to

translate into English in a three-volume edition of 1846. Just to give you some

idea, Sue was also responsible for Les Mystères de Peuple, parts of

which were plagiarised by Maurice Joly as The Dialogue in Hell Between

Machiavelli and Montesquieu elements of which were, in turn, plagiarised by

the authors of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Although proved to

be a forgery in the 1920s, Hitler and his cronies eagerly seized upon the Protocols

as a justification for their genocide of the Jews (and anyone else they

imagined didn’t deserve to continue living). And we all know what happened

next.

No comments:

Post a Comment