The philosopher Jagger was quite right when he said,

“You can’t always get what you want,” but the thing is that, sometimes,

you do get what you want. And when that happens, there is always a

danger that you will want even more. Ignatius Loyola Donnelly got what he

wanted. He found a cipher hidden in the first folio of Shakespeare’s plays, so

he set about looking for more of the same.

|

| Ignatius Donnelly |

That’s where the trouble starts. As

he says himself,

“I invented hundreds of ciphers in trying to solve this one. Many times I was in despair. Once I gave up the whole task for two days.”

And there is the clue. He was determined to find something else, no matter

what. Now, sometimes, determination is a Good Thing, you need a little

application to keep things ticking over, but sometimes determination tips over

into obsession, and that’s a Bad Thing. That Donnelly gave up for two whole

days sounds to me like he was just a wee bit obsessed, if he couldn’t leave it

alone for longer than that. That, and the ‘hundreds of ciphers’ business.

Anyway, Donnelly rolled up his sleeves and applied himself to his task like he

was being paid for it. He reasoned that Francis Bacon might refer to a ‘volume’

or ‘the volume’ if he was talking about a book and on page 75 of the Histories,

sure enough,

“Yea, this man's brow, like to a title-leaf,Foretells the nature of a tragic volume.”

|

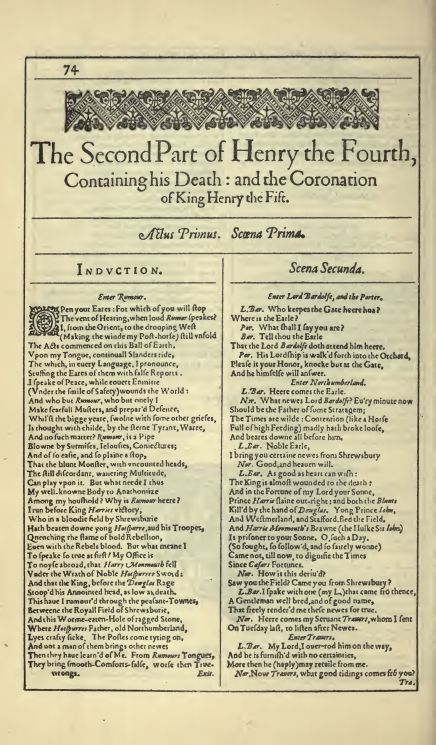

| Shakespeare First Folio - Page 74 |

Then, it was back to the counting. In the first

column of page 74 of the first folio, there were 284 words, in the second

column on the same page there were 248 words, and the word ‘volume’ was

word number 208 in the first column of page 75. 284 + 248 + 208 = 740. And on

page 74, there are ten words in italics – 740 divided by 10 = 74, the number of

the page! Donnelly’s ingenuity now goes into overdrive. If one deducts 10 from

the number of words in the first column on page 75, (447 words) and counts down

the column, the 437th word is ‘doing’ whereas if one counts

up from the bottom of the column, the tenth word is ‘me’; thus, reasoned

Donnelly, if one is to use the reverse count, one needs to add an extra word to

reveal the coded word.

|

| Ignatius Donnelly |

Using this logic, Donnelly counted back up the first

column and found that the 208th word is ‘mask’. Surely an

indication that something is hidden. He continues this counting forwards and backwards,

adding and subtracting, marking and noting, beginning at the top and bottom of

the columns but also counting from the breaks caused by the various stage

directions in the text. He also considers the original publication of the

plays, that they were first printed in quarto editions, so that the page

numbering and word counts on the pages were necessarily different.

This is all

part of Bacon’s cunning plan, says Donnelly, because even if there were

suspicions that a message might be hidden in the plays, the code would be

impossible to discover as the numbering combinations needed to decode the

message did not exist. So for twenty years, Francis Bacon sat on the plays and

waited until any suspicion had fallen away and many of the people involved (Elizabeth

I, Leicester, Cecil etc) were long dead. Then, in 1623, the first folio was

issued and Bacon could re-issue the familiar plays in the version he had long

intended. If all that sounds wildly

implausible, then you too have fallen for Bacon’s cunning plan and you have

also been duped by his superior intellect.

|

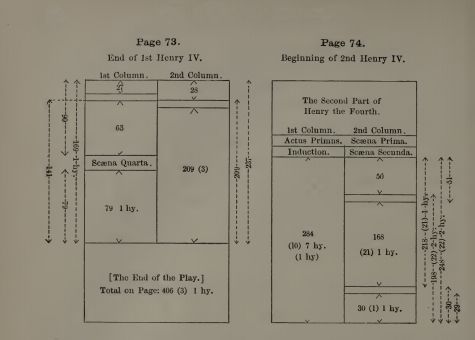

| Donnelly's Diagram showing how his method works |

You can also get some idea of the

complicated nature of the cipher by the diagram that Donnelly uses to explain

his findings, with the relationships between the assorted ratios of words per

page, words per column and the differences between them shown alongside the

page set outs. Eventually, and he does not reveal in his book how he arrived at

them, Donnelly comes up with the core code of his decipherment – the numbers

are 505, 506, 513, 516 and 523 – and by assorted combinations of multiplying,

adding, subtracting, ratios and factors, Donnelly reveals the secret messages

hidden in the plays.

|

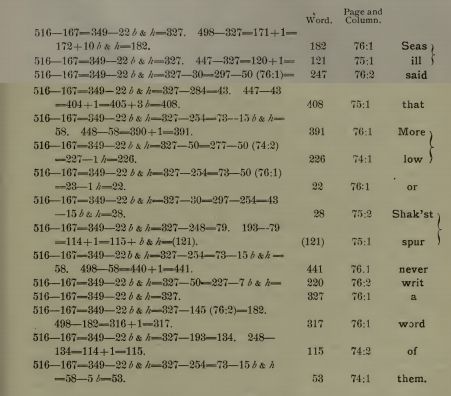

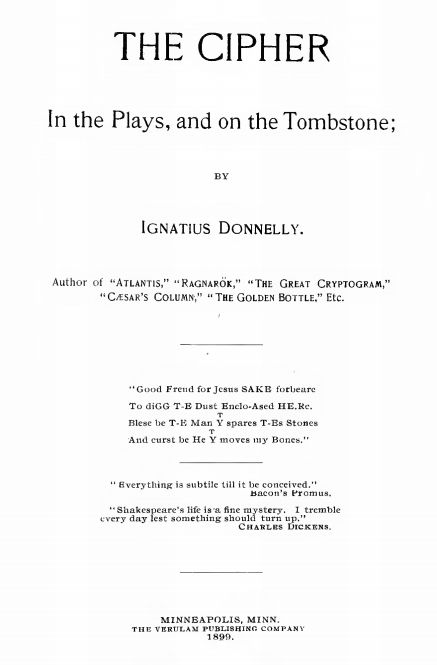

| Seas Ill Said That More Low or Shak'st Spur Never Writ A Word Of Them |

You can see his numerical jiggery-pokery in this example,

where he shows us how Cecil (his name created from seas and ill)

reveals that neither Marlowe (more low) nor Shakespeare (shak’st spur)

did not write a single word of the plays. The numbers on the left are

Donnelly’s core numbers with the various additions and subtractions and so

forth worked out. See how simple it all is?

|

| It Is Even Thought Here That Your Cousin Of St Albans Writes Them. |

Using his convoluted calculations,

Donnelly untimely rips a variety of stories out of the plays – how Marlowe was

killed, how Shakespeare left his wife in Stratford and went to London, how

Elizabeth suspected that the play Richard II was treasonous and so on

and so forth. When Donnelly finished all his adding and subtracting, he

published The Great Cryptogram in 1888, and, unsurprisingly, the critics

battered it. One writer, Joseph Pyle, went so far as to publish his own Tiny

Cryptogram, and by using Donnelly’s own method of calculation revealed that

within the play Hamlet was hidden the message,

“Donnelly, writer, politician, and a charlatan, revealed the secret of this play.”

|

| Ignatius Donnelly - The Cipher In the Plays and on the Tombstone - 1899 |

Undeterred,

Donnelly went on and published another book, The Cipher in the Plays and on

the Tombstone (1899) but like its predecessor, this book also failed to

sell. It’s another barmy construction in which Donnelly’s loonometer is turned

all the way up to eleven as he turns his gaze onto Shakespeare’s tombstone and

the Sonnets, revisits Bacon and the plays and throws some Rosicrucianism into

the mix, just for good measure. If you like your bonkers served hot and strong,

Ignatius Loyola Donnelly might just be the very crackpot that is your cup of

tea.

No comments:

Post a Comment