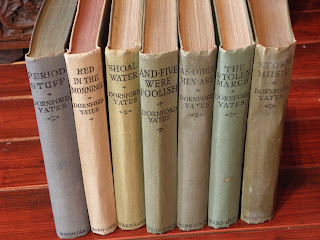

We all have our guilty pleasures, those little indulgences we take in secret and furtively enjoy whilst squirming internally at the delight they bring. I enjoy reading the novels of Dornford Yates.

It’s unlikely that you know the name, as he long fell out of favour, but in the interwar years he was one of the most popular and widely read British authors. Born Cecil William Mercer in 1885, he took his pen name by combining the surnames of his grandmothers. Mercer read law at Oxford, where he was heavily involved in student dramatics, which probably accounts for his leaving with a third, not a good enough degree to enter the bar. His father, a solicitor, exploited a loophole to get his son into chambers by the backdoor, and Mercer became a junior barrister. In the spare time he had between cases he began to write stories, which were published, and Mercer eventually gave up the law to become a full time writer.

His novels fall into three groups – the Berry books, the Chandos books, and other books that are either thrillers or collections of short stories.

His Berry books feature Bertram ‘Berry’ Pleydell, his wife (and cousin) Daphne, her brother Boy Pleydell (who narrates the stories), and their cousins Jonathan ‘Jonah’ Mansell and his sister Jill; together they are known as ‘Berry and Co.’ They are light, romantic tales, as the five upper-class Edwardians drift across the Home Counties and continental Europe in Rolls Royces, visit vast country estates and get into various scrapes and adventures, in which they invariably outwit their lower-class or foreign antagonists. They are incredibly snobbish, speak in an outlandish affected manner, and epitomise the lost world of their class in the years between the end of the First World War and beginning of Corporal Hitler’s Unpleasantness. As their fortunes decline and social attitudes change, they move to France where they build a new house (The House That Berry Built), called Gracedieu, mirroring Yates’s own move to Pau, in the French Pyrennes, where he too built a house, Cockade.

The Chandos novels are thrillers, featuring Richard Chandos and his friends George Hanbury and Jonathan Mansell (from the Berry series), both of whom had been sent down from Oxford for beating up ‘Bolshies’. Set mainly in Europe, often Austria, the three adventurers fight crime, hunt for buried treasure, rescue damsels in distress, get the better of foreign gangsters and, in Alan Bennett’s words, indulge in ‘Snobbery with violence’. They are firmly in the Boy’s Own Paper genre of adventure stories, of Englishmen with firm jaws and stiff upper lips, in the manner of Bulldog Drummond and Richard Hanney. They have all had a ‘good’ war; Mansell was wounded at Cambrai and walks with a limp – which he never mentions. Mercer, in contrast, was posted to Egypt, where he contracted severe muscular rheumatism and was sent home, (unlike his cousin, H H Munro, better known as the novelist ‘Saki’, who was killed in action, shot by a German sniper at the Somme), but he retained his captaincy as a permanent title when he returned to civilian life. He fled from Pau after the Germans invaded France and settled in Rhodesia, where he died in 1960. He was, by all accounts, a very disagreeable man.

In a sub-plot in The House That Berry Built, the murderer Shapely attempts to dispose of a body with quick lime, but Boy Pleydell confronts him, “I’d put him wise, in the train. I’d shown him the fatal error which he had made. He’d slaked his lime – like Crippen. I remember using these words – ‘Quick lime destroys, but slack lime preserves.”

On the train Pleydell says to Shapely, “I can only remember Crippen.”

”’Only’ ? “ cried Shapely. “My God, you weren’t in that ?”

“From beginning to end,” said I.

“You helped to prosecute Crippen?”

“I did.”

This was perfectly true.

And it is autobiographically true. As a junior barrister, Mercer had been at the trial of Crippen. Hawley Harvey Crippen, popularly known as Dr Crippen, was the first criminal to be apprehended by use of wireless telegraphy.

|

| Dr H H Crippen |

Born in Coldwater, Michigan, in 1862, Crippen qualified as a homeopathic doctor in 1884. In 1897 he moved, with his second wife Cora, to London, but his US qualifications were not enough to allow him to practice as a doctor, so he took a job selling patent medicines. Cora gained employment as a music hall singer, and moved in theatrical circles; Crippen was eventually sacked for spending too much time promoting her career. He became the manager of a deaf school, where he met a typist, Ethel Le Neve, who became his mistress. The Crippens started a boarding house, and Cora had an affair with at least one of the lodgers. The marriage began to unravel, and she threatened to leave Crippen, taking their not insubstantial joint savings with her.

Then, in January 1910, Cora disappeared. Her friends, upset that Ethel had been seen wearing her furs and jewellery, asked the police to investigate and Crippen was interviewed by Chief Inspector Walter Dew. The Crippen’s house was searched, but nothing was found. But Crippen panicked, and he and Ethel fled, first to Brussels, then to Antwerp, where they boarded SS Montrose, bound for Canada. Their flight raised suspicions and the house was searched again, eventually revealing a torso buried beneath the brick floor of the cellar. The head, limbs and skeleton were never found. On board SS Montrose, Captain Kendall sent the following telegram to the British police - "Have strong suspicions that Crippen London cellar murderer and accomplice are among saloon passengers. Mustache taken off growing beard. Accomplice dressed as boy. Manner and build undoubtedly a girl."

Inspector Dew immediately left for Canada on the faster ship SS Laurentic, arriving in Quebec before Crippen, where he confronted and arrested him. Canada was a British Dominion, so although Crippen was an American citizen he was returned to England without the need for an extradition order. He was tried for the murder of Cora at the Old Bailey. Crippen had, it was said, buried the body in quicklime which, when dry, would destroy the remains, but he had wetted the lime with water, which turned it to slaked lime, a preservative. Various pathologists, including Bernard Spilsbury, were unable to identify Cora from the remains, but other evidence pointed to Crippen as the murderer, and on October 22nd 1910, he was found guilty and hanged at Pentonville Prison on November 23rd. Ethel Le Neve was acquitted, at a separate trial, of being an accessory after the fact, and, on the morning of Crippen’s execution, emigrated to the US, but she later returned, married and started a family.

|

| The Verdict - from the Proceedings of the Old Bailey, October 1910 |

No comments:

Post a Comment