Percy Bysshe Shelley was born in

Sussex on August 4th 1792, the son of Sir Timothy Shelley, a

gentleman landowner so dull, it was said, he “… was secured from all risk of

aberration from the social conventions by a happy inaccessibility to ideas.”

Percy’s grandfather, Bysshe, received a baronetcy in 1806, and began to build,

at great expense, Castle Goring, a magnificent country seat although, towards

the end of his life, he became a notorious miser.

|

| Percy Bysshe Shelley |

In his boyhood, young Percy

spent most of his time in country pursuits, fishing and hunting, but at ten

years old he was sent to Syon House Academy, a school not yet entirely

Dotheboy’s Hall but harsh enough, where he was bullied mercilessly.

|

| Syon House |

In 1804, he

attended Eton, where his refusal to conform to the ‘fagging’ system ensured he

was bullied by boys and masters alike, and in 1810, he entered University

College, Oxford but was expelled the following year for failing to repudiate

the authorship of a pamphlet The Necessity of Atheism.

Later in 1811,

Shelley eloped with the sixteen-year old Harriet Westbrook to Gretna Green,

where they were married, causing Sir Timothy to cut off his allowance, for

marrying beneath him. The marriage was unhappy, not least because Harriet

insisted her elder sister, Eliza, live with them (Shelley hated both the sister

and the arrangement). Shelley travelled to Keswick in the Lake District to see

the poet Southey, whom he presumed was still politically active, and who

advised him to contact William Godwin, author of Political Justice.

|

| William Godwin |

Godwin

was penniless and trying to support his large family, and saw Shelley as a

potential source of income; he had two adopted step-daughters, Fanny Imlay and

Claire Clairmont, and a daughter, Mary, from his second wife, Mary

Wollstonecraft, (who had died of fever 10 days after her birth). Harriet (now

pregnant with Shelley’s son, Charles) and sister Eliza (together with Shelley’s

infant daughter, Elizabeth), moved back to their parent’s home; in July 1814,

Shelley abandoned his wife and travelled across France to Switzerland with Mary

Godwin and her half-sister Claire (both aged 16), returning destitute after six

weeks.

|

| Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley |

Two years later, in 1816, Shelley, Mary and Claire returned to

Switzerland, where they stayed with Lord Byron and his doctor, John Polidori,

and in June, Mary began to write Frankenstein. Later in 1816, after

their return to England, Fanny Imlay travelled from London to Swansea where, on

the night of October 9th, she killed herself with an overdose of

laudanum; there have been various theories as to why, but no clear evidence –

some say it was unrequited love for Shelley. In December 1816, Harriet

Shelley’s heavily pregnant corpse was taken from the Serpentine, where she had

drowned herself; Shelley and Mary Godwin married three weeks later. In 1818,

Shelley, Mary and Claire returned to Italy, to deliver Claire’s daughter,

Allegra, to Byron, her father and Shelley, encouraged by Byron wrote some of

his best works. Later in the year, William Shelley, the three-year old son born

out of wedlock, died of fever in Rome, and the following year, their daughter,

Clara, also died.

|

| The Peterloo Massacre |

Shelley continued to write, including The Mask of Anarchy,

which was a response to the Peterloo massacre, and Prometheus Unbound, a

lyrical drama in four acts, works for which he was probably best known in the

nineteenth century. In July 1822, whilst sailing back from Leghorn, Shelley’s

schooner was hit by a storm; his body was washed ashore and, due to quarantine

regulations, was cremated on the beach at Viareggio. He was twenty-nine.

|

| The Cremation of Shelley at Viareggio |

Theories about the cause of Shelley’s death are legion; some say it was purely

an accident, some say he fell foul of robbers or pirates, some hint at suicide

and yet others are sure it was a politically motivated assassination.

|

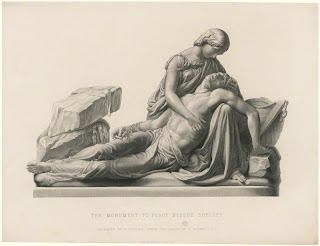

| Memorial Statue to Shelley |

Shelley’s poetic reputation was

not great during his lifetime, as his political radicalism was not well

received in some circles. The critic Matthew Arnold tried to marginalise him,

referring to him as ‘beautiful and ineffectual angel’, but the

Pre-Raphaelites, other poets and early socialists were among the first to appreciate

him. His status continued to rise during the twentieth century as his works

became more readily available and unpublished works were published, and his

political message remains just as relevant in our time.

“Rise like Lions after slumberIn unvanquishable number —Shake your chains to earth like dewWhich in sleep had fallen on you —Ye are many — they are few.”

The Mask of Anarchy

No comments:

Post a Comment